![]()

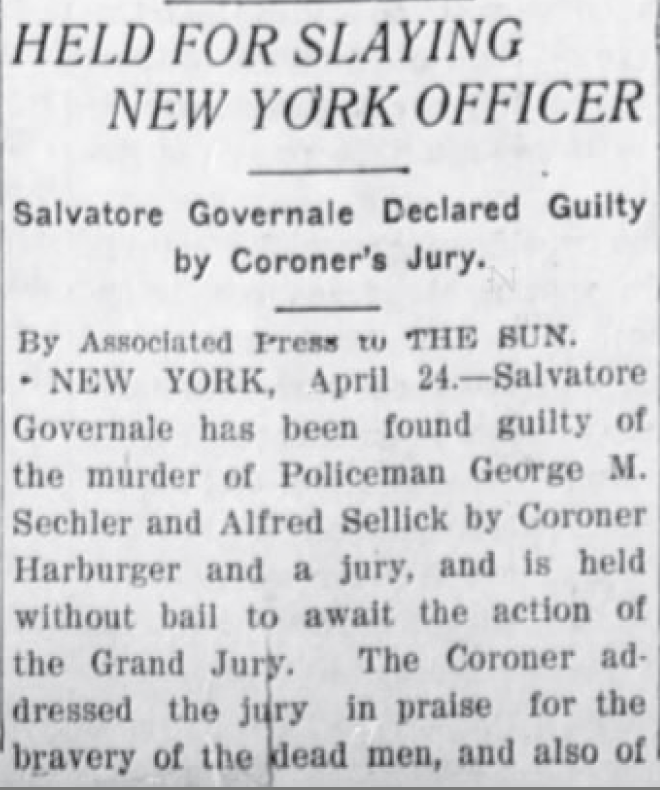

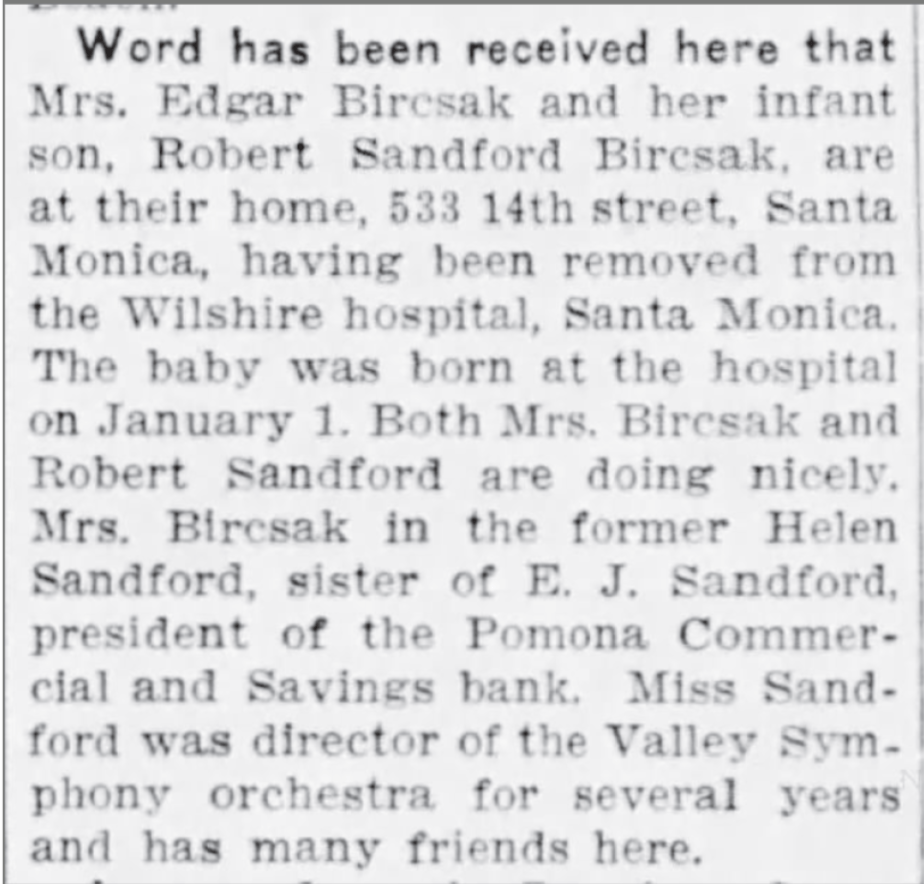

![]() Great grandfather Edward Sandford was not our only ancestor to fight in the United States Civil War. Our second great grandfather Aaron Sechler, the father of our great grandfather George Sechler, served in the war for three years. Although they were a generation apart, Aaron Sechler was only three years older than Edward.

Great grandfather Edward Sandford was not our only ancestor to fight in the United States Civil War. Our second great grandfather Aaron Sechler, the father of our great grandfather George Sechler, served in the war for three years. Although they were a generation apart, Aaron Sechler was only three years older than Edward.

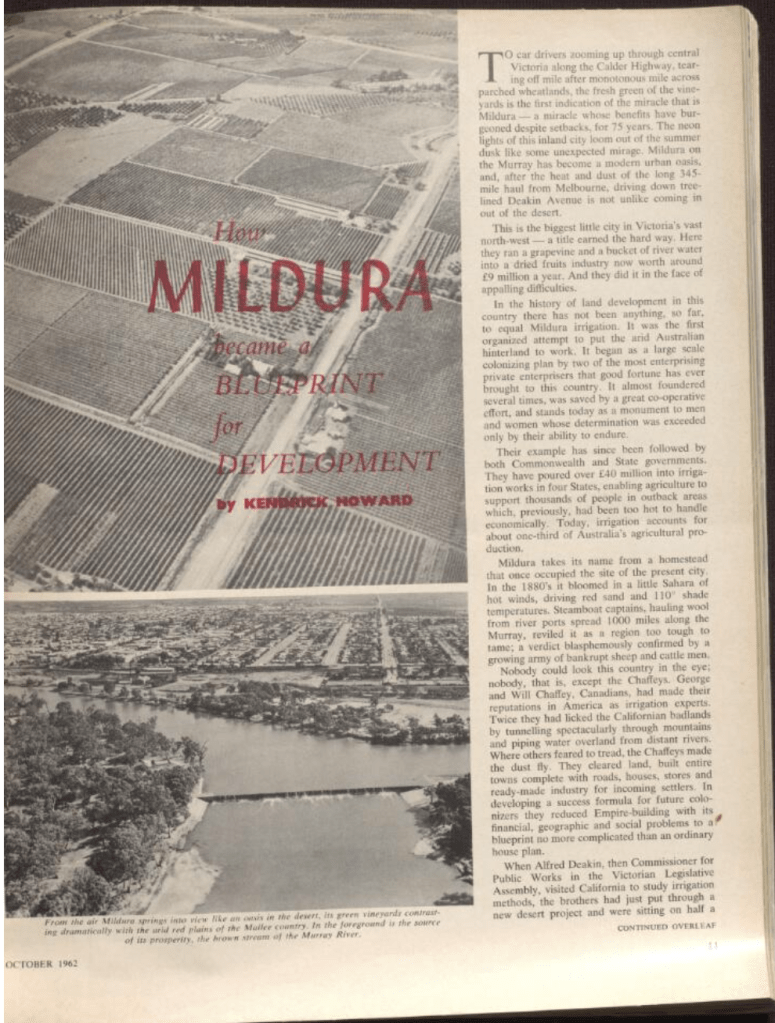

The 1860 U.S. Census shows 22 year old Aaron living in Danville with his family, including two brothers and two sisters. Aaron’s father Jacob was a farmer (referred to as Jacob Jr. because he lived with his uncle Jacob after the death of his father Joseph in 1804.)

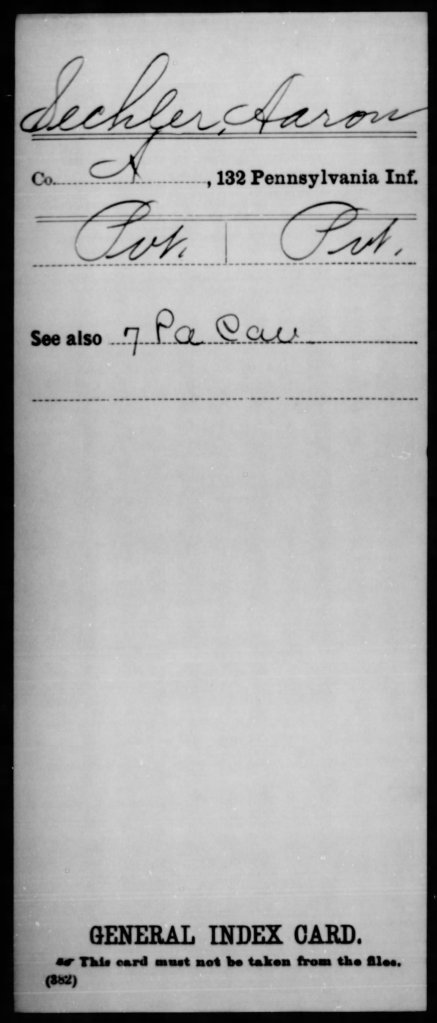

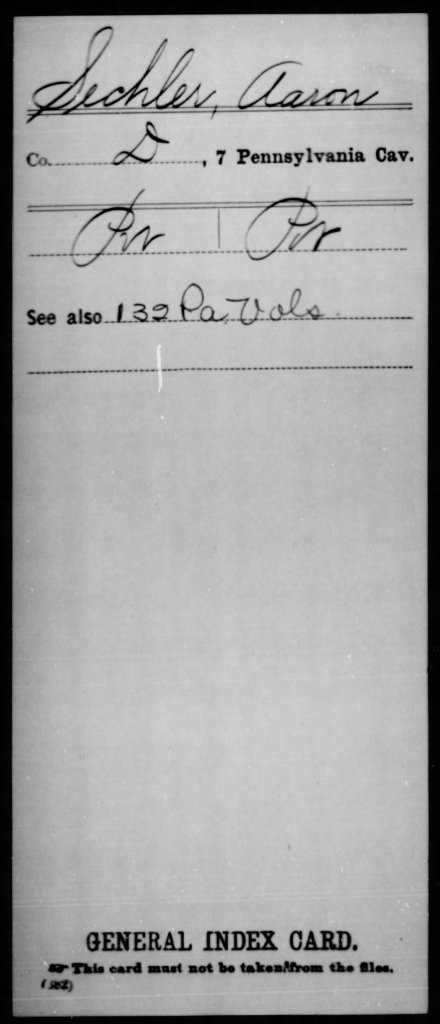

Aaron’s war records indicate that he served in two units during the war, the 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry and the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Records of the 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry show that it was in action earlier in the war, between August 1862 and May 1863, and that it moved up the Potomac River from the Washington DC region, participating in the Battle of Antietam, then back through Harper’s Ferry and into Virginia where it fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

The 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry was organized at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in August 1862 and mustered in under the command of Colonel Richard A. Oakford.

The regiment was attached to 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, II Corps, Army of the Potomac, to November 1862. 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, II Corps, to May 1863.

The 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry mustered out May 24, 1863.

Detailed Service: Moved to Washington, D.C., August 19, and performed duty there until September 2. Ordered to Rockville, Md., September 2. Maryland Campaign September 6-22, 1862. Battle of Antietam, Md., September 16-17. Moved to Harpers Ferry, Va., September 22, and duty there until October 30. Reconnaissance to Leesburg October 1-2. Advanced up Loudon Valley and movement to Falmouth, Va., October 30-November 17. Battle of Fredericksburg December 12-15. Duty at Falmouth until April 27. Chancellorsville Campaign April 27-May 6. Battle of Chancellorsville May 1-5.

The regiment lost a total of 113 men during service; 3 officers and 70 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded, 40 enlisted men died of disease.

Wikipedia

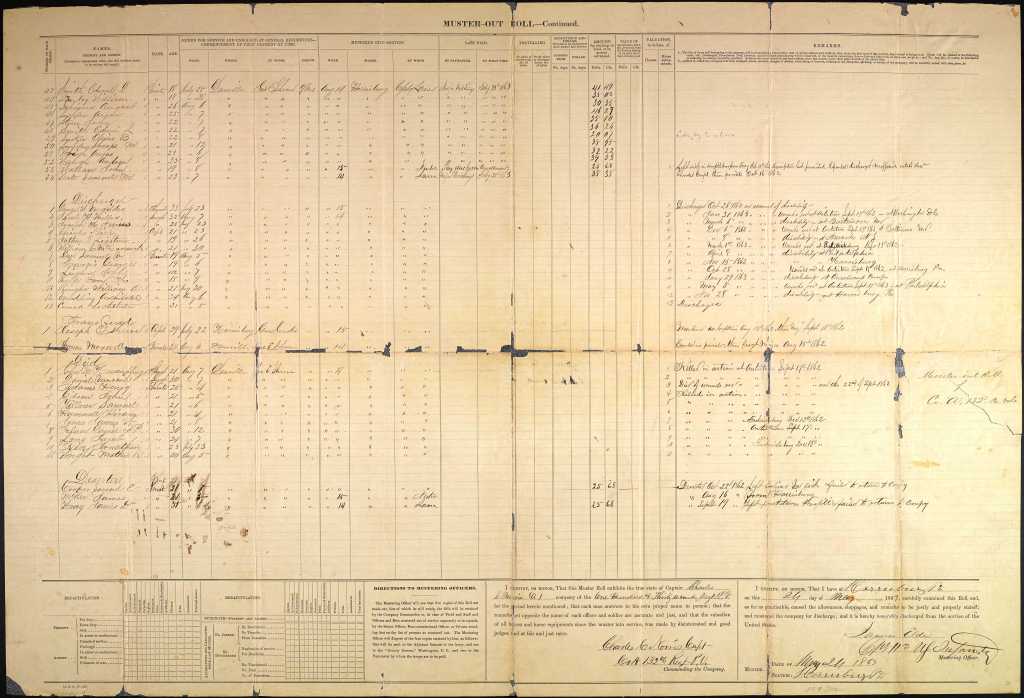

Muster-Out Roll records from the 132nd confirm that Aaron joined the unit on August 7, 1862 and remained with the unit through its decommissioning. That Aaron’s name does not appear on a separate list of men discharged from duty at that time is consistent with other sources showing that he remained in service after his tour with the 132nd was complete.

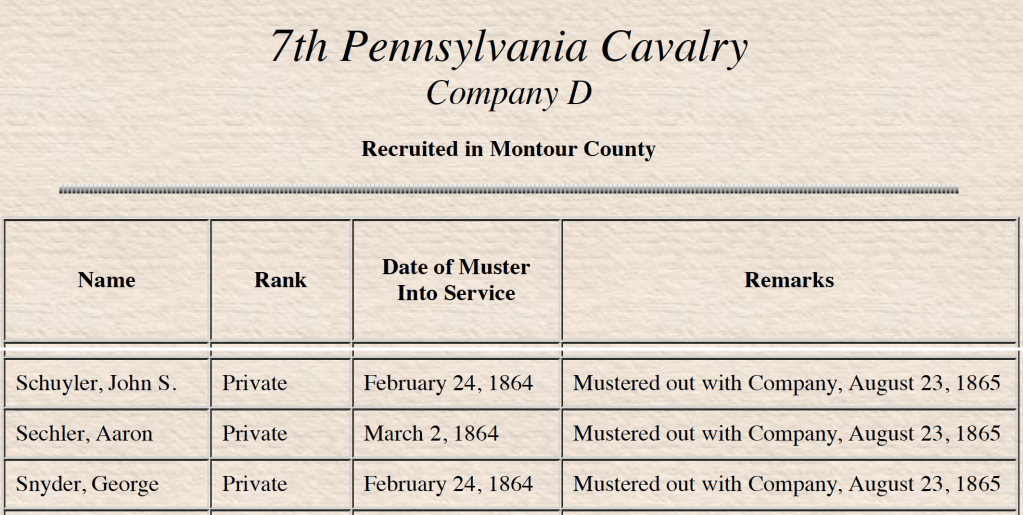

A year later, Aaron appears in records affirming his attachment to the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry, where he remained through August 1865.

By 1864, the war had moved deep into the South (this being the time when General Sherman was driving toward the burning of Atlanta in July). Records of the 7th Cavalry list its involvement in many campaigns in locations in Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama.

The 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry was organized at Camp Cameron in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania September through December 1861 and mustered in for a two-year enlistment on December 19, 1861, under the command of Colonel George C. Wynkoop. The regiment was recruited in Allegheny, Berks, Bradford, Centre, Chester, Clinton, Cumberland, Dauphin, Luzerne, Lycoming, Montour, Northumberland, Schuylkill and Tioga counties.

The regiment served unattached, Army of the Ohio, to March 1862. Negley’s 7th Independent Brigade, Army of the Ohio (1st Battalion). Post of Nashville, Tennessee, Department of Ohio (2nd Battalion). 23rd Independent Brigade, Army of the Ohio (3rd Battalion), to September 1862. Cavalry, 8th Division, Army of the Ohio (1st and 2nd Battalions), Unattached, Army of the Ohio (3rd Battalion), to November 1862. 1st Brigade, Cavalry Division, Army of the Ohio, to January 1863. 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, Army of the Cumberland, to November 1864. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Cavalry Corps, Military Division Mississippi, to July 1865.

The 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry mustered out of service at Nashville, Tennessee, on August 13, 1865.

Detailed Service: Moved to Louisville, Ky., December 19, and ordered to Jeffersonville, Ind. Duty there until February 1862. 1st Battalion (Companies A, D, H, and I) sent to Columbia, Tenn. Expedition to Rodgersville May 13–14. Lamb’s Ferry, Ala., May 14. Advance on Chattanooga June 1. Sweeden’s Cove June 4. Chattanooga June 7–8. Occupation of Manchester July 1. Paris July 19. Raid on Louisville & Nashville Railroad August 19–23. Huntsville Road, near Gallatin, August 21. Brentwood September 19–20. Near Perryville October 6–7. Battle of Perryville, October 8. Expedition from Crab Orchard to Big Hill and Richmond October 21. 2nd Battalion (Companies C, E, F, and K), under Gen. Dumont, in garrison at Nashville, Tenn., and scouting in that vicinity until November. 3rd Battalion (Companies B, G, L, and M), in Duffield’s Command, scouting in western and middle Tennessee. Lebanon and pursuit to Carthage May 5. Readyville June 7. Murfreesboro July 18. Sparta August 4–5 and 7. Regiment reunited in November 1862. Nashville November 5. Reconnaissance from Nashville to Franklin December 11–12. Wilson’s Creek Pike December 11. Franklin December 12. Neal, Nashville December 24. Advance on Murfreesboro December 26–30. Lavergne December 26–27. Battle of Stones River December 30–31, 1862 and January 1–3, 1863. Overall’s Creek December 31. Manchester Pike and Lytle’s Creek January 5, 1863. Expedition to Franklin January 31-February 13. Unionville and Rover January 31. Murfreesboro February 7. Rover February 13. Expedition toward Columbia March 4–14. Unionville and Rover March 4. Chapel Hill March 5. Thompson’s Station March 9. Rutherford Creek March 10–11. Snow Hill, Woodbury, April 3. Franklin April 10. Expedition to McMinnville April 20–30. Middletown May 21–22. Near Murfreesboro June 3. Operations on Edgeville Pike June 4. Marshall Knob June 4. Shelbyville Pike June 4. Scout on Middleton and Eagleville Pike June 10. Scout on Manchester Pike June 13. Expedition to Lebanon June 15–17. Lebanon June 16. Tullahoma Campaign June 23-July 7. Guy’s Gap or Fosterville and capture of Shelbyville June 27. Expedition to Huntsville July 13–22. Reconnaissance to Rock Island Ferry August 4–5. Sparta August 9. Passage of Cumberland Mountains and Tennessee River, and Chickamauga Campaign August 16-September 22. Calfkiller River, Sparta, August 17. Battle of Chickamauga September 19–20. Rossville, Ga., September 21. Reenlisted at Huntsville, Ala., November 28, 1863. Atlanta Campaign May to September 1864. Demonstration on Rocky Faced Ridge May 8–11. Battle of Resaca May 14–15. Tanner’s Bridge and Rome May 15. Near Dallas May 24. Operations on line of Pumpkin Vine Creek and battles about Dallas, New Hope Church and Allatoona Hills May 25-June 5. Near Big Shanty June 9. Operations about Marietta and against Kennesaw Mountain June 10-July 2. McAffee’s Cross Roads June 11. Powder Springs June 20. Noonday Creek June 27. Line of Nickajack Creek July 2–5. Rottenwood Creek July 4. Rossville Ferry July 5. Line of the Chattahoochie July 6–17. Garrard’s Raid on Covington July 22–24. Siege of Atlanta July 22-August 25. Garrard’s Raid to South River July 27–31. Flat Rock Bridge July 28. Kilpatrick’s Raid around Atlanta August 18–22. Flint River and Jonesborough August 19. Red Oak August 19. Lovejoy’s Station August 20. Operations at Chattahoochie River Bridge August 26-September 2. Operations in northern Georgia and northern Alabama against Hood September 29-November 3. Carter Creek Station October 1. Near Columbia October 2. Near Lost Mountain October 4–7. New Hope Church October 5. Dallas October 7. Rome October 10–11. Narrows October 11. Coosaville Road, near Rome, October 13. Near Summerville October 18. Little River, Ala., October 20. Leesburg October 21. Ladiga, Terrapin Creek, October 28. Ordered to Louisville, Ky., to refit; duty there until December 28. March to Nashville, Tenn., December 28-January 8, 1865, thence to Gravelly Springs, Ala., January 25, and duty there until March. Wilson’s Raid to Selma, Ala., and Macon, Ga., March 22-April 24. Selma April 2. Occupation of Montgomery April 12. Occupation of Macon April 20. Duty in Georgia and at Nashville, Tenn., until August.

The regiment lost a total of 292 men during service; 8 officers and 94 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded, 5 officers and 185 enlisted men died of disease.

Wikipedia

Altogether Aaron served two tours of duty separated by a year away from action, the first tour about 9 months long, the second 17 months. Determining Aaron’s exact roles in the battles fought by the 7th and 132nd would be a good topic for future research. In any case, this is an extraordinary amount of time to be serving under such difficult conditions, facing so many significant battles and skirmishes along the way.

By contrast, Edward Sandford enlisted in June 1863 (recall that he was sailing in Asian waters when the war started) and only reached the war front in the spring of 1864. His path took him directly south from Washington DC through Virginia and North Carolina. By mid-June he had been wounded and was making his way back north through various hospitals and stages of recovery.

So the two men were fighting at the same time in the same broad offensive for a couple months in 1864, but several hundred miles apart. This is as close as they came to crossing paths.

Aaron returned to Danville and was married to Rebecca Roberts a short time later in 1865. They had six children between 1866 and 1879, including fourth child George who was born in 1873.

Having survived a war where as many died of disease as from fighting, Aaron succumbed to typhoid pneumonia in 1887, at age 50, when George was 13.