Having established that our second great grandfather Aaron Sechler (father of New York police officer George Sechler) completed two tours of duty in the Civil War, and having noted that Aaron’s first regiment, the Pennsylvania 132nd Infantry, took part in the infamous Battle of Antietam, I wanted find evidence that Aaron himself was actually at Antietam. I found this and much more.

Having established that our second great grandfather Aaron Sechler (father of New York police officer George Sechler) completed two tours of duty in the Civil War, and having noted that Aaron’s first regiment, the Pennsylvania 132nd Infantry, took part in the infamous Battle of Antietam, I wanted find evidence that Aaron himself was actually at Antietam. I found this and much more.

The Pennsylvania 132nd Infantry existed between August 1862 and May 1863 (extending its originally planned nine month tour by about a month). It was recruited from a half-dozen Pennsylvania towns between Danville and Scranton at a time when the Union was panicking about early defeats in battles in Virginia at Chantilly and the Second Bull Run. The regiment started out at a strength about 1000 men and finished with about 600.

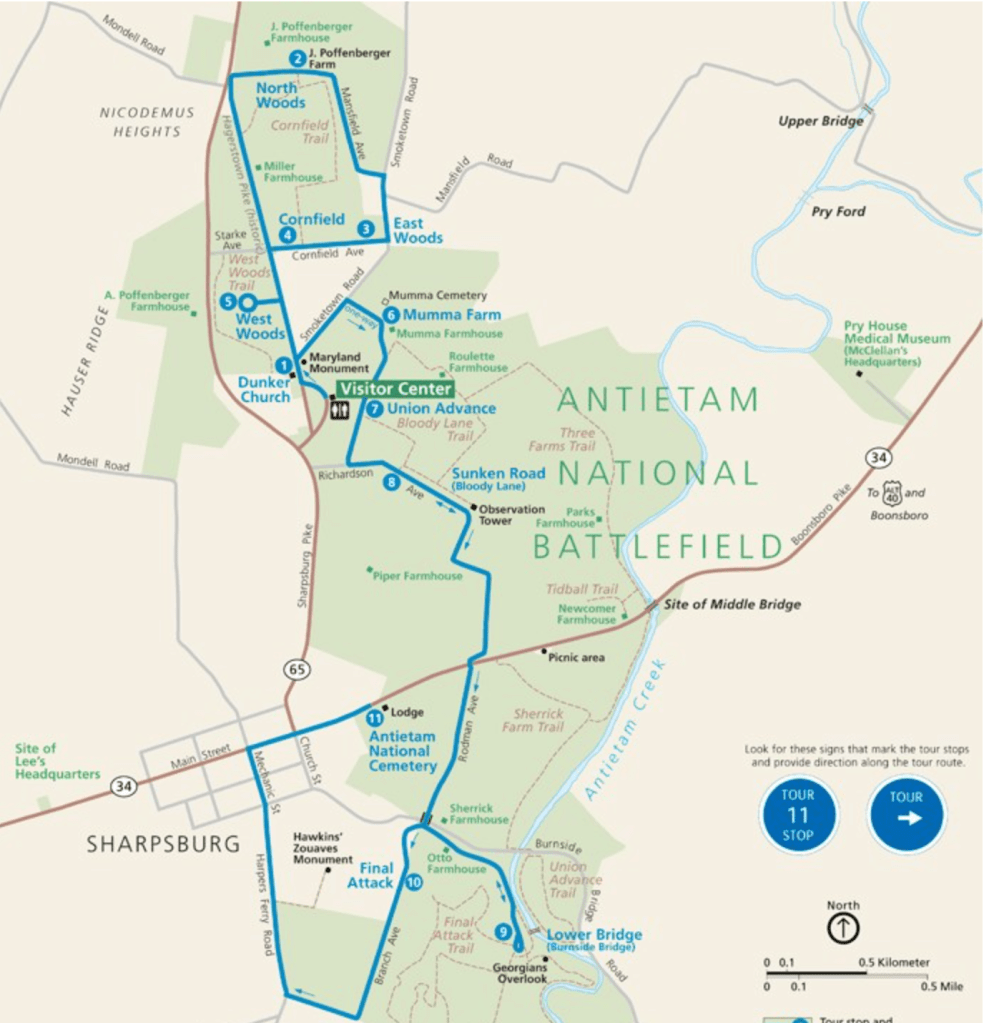

On a recent visit to the Antietam National Battlefield, it took a mere mention of the PA 132nd to spur the park ranger off to the back room to return three minutes later with a 22 page printout detailing everything one might want to know about this regiment’s role in the battle. (They have a list of about 75 other regiments for which they can do the same thing.)

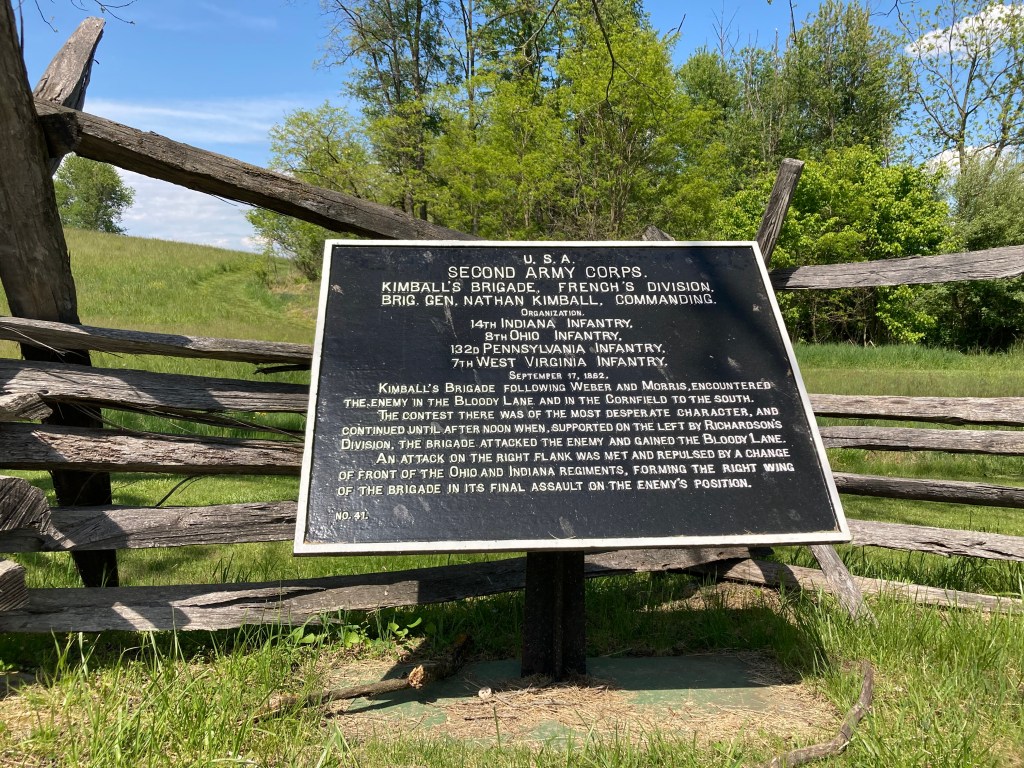

The PA 132nd fought in the Bloody Lane (or Sunken Road) battle, one of the three massive confrontations that took place at Antietam on September 17, 1862 (the other two being The Cornfield and Burnside’s Bridge).

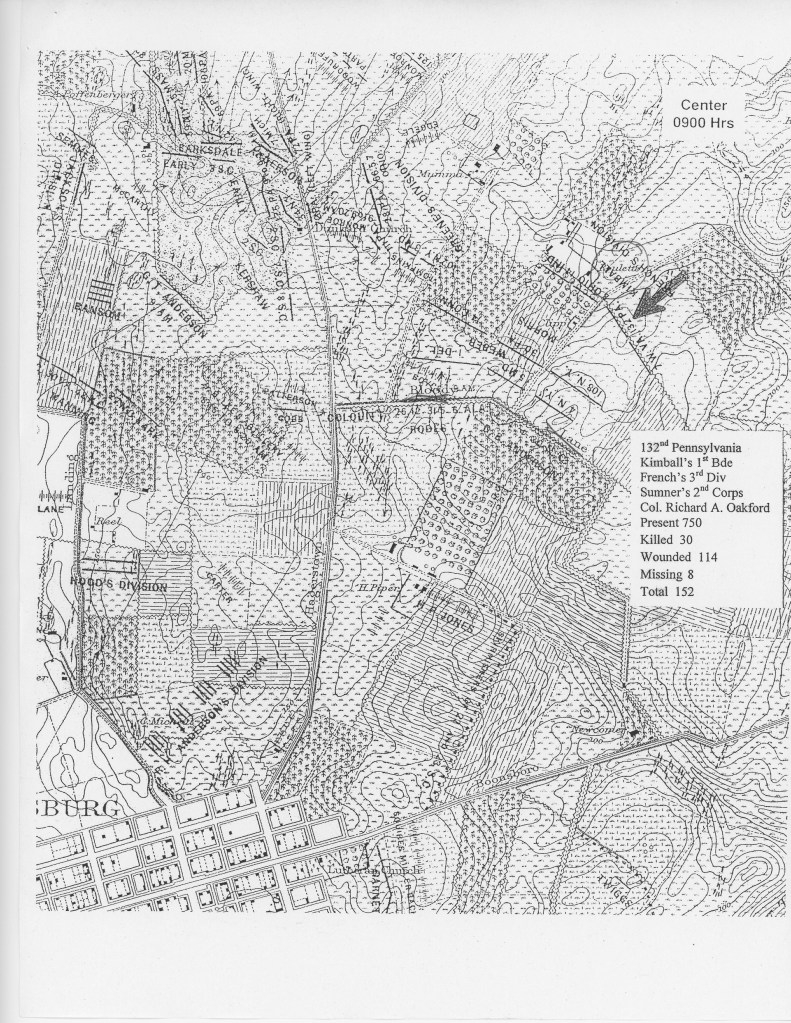

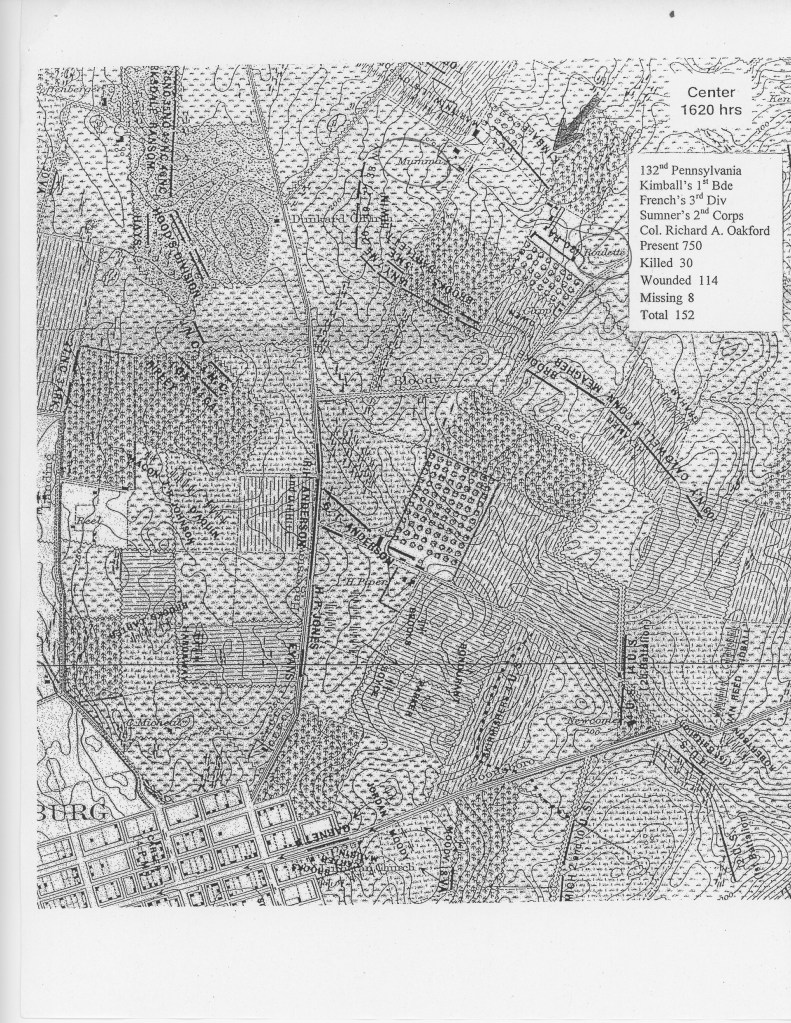

The information provided by the Park Service about the PA 132nd includes maps showing their location every hour on the day of the battle. Having made camp the previous night in Keedysville MD, a couple miles east of what would become the battlefield, the regiment made its way west in the early morning and by 8am was at Roulette’s Farm, within sight of the Sunken Road and the Confederate forces occupying it. The PA 132nd were joined that day by three other Union regiments from Indiana, Ohio, and West Virginia.

The two forces exchanged heavy fire through the late afternoon when the Rebel forces were finally pushed back. Antietam is considered to be the bloodiest single-day battle of the war. Of 100,000 soldiers who entered the Battle of Antietam, about 23,000 were killed, wounded or went missing, with Union casualties outnumbering those of the Confederacy. Although the Union forces held the field, Lee’s Confederate forces were able to withdraw to Virginia and the war’s overall battle lines were not significantly changed by the day’s fighting.

The Emancipation Proclamation would take effect the following January, and the Battle of Gettysburg would take place the following July.

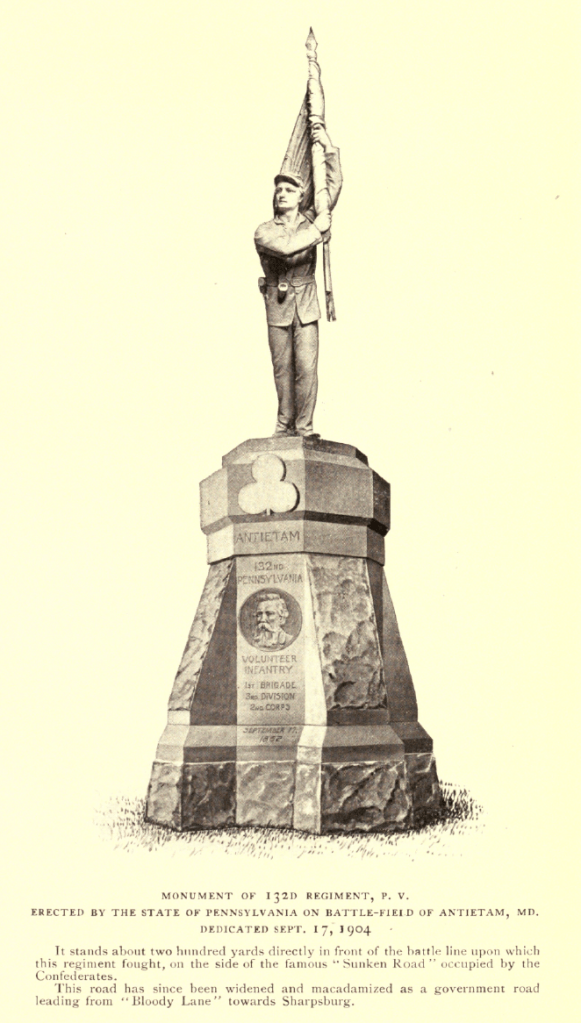

Today, the PA 132nd’s role in the Bloody Road fight is commemorated by a large statue of a young soldier holding a flag, the bottom of the standard of which has just been broken off by a bullet. This image provides the backdrop for the next part of our story.

Listening-in on the talk of a tour guide passing through the Sunken Road area of the park, I learned of a book written by one of the officers of the PA 132nd, Major Frederick Lyman Hitchcock (who retired as a Colonel). Upon returning home, it took about five minutes to find and download a complete copy of the book, which has long-since passed into the public domain.

The book, War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863, is highly recommended reading. Hitchcock was with the 132nd for its entire existence between mid-August, 1862 and late-May, 1863. He kept a diary during and wrote the book after the war. It goes into detail on everything the regiment encountered and did, from major battles to daily life in camp. It is written in a way that it could have been narrated by anyone in the division.

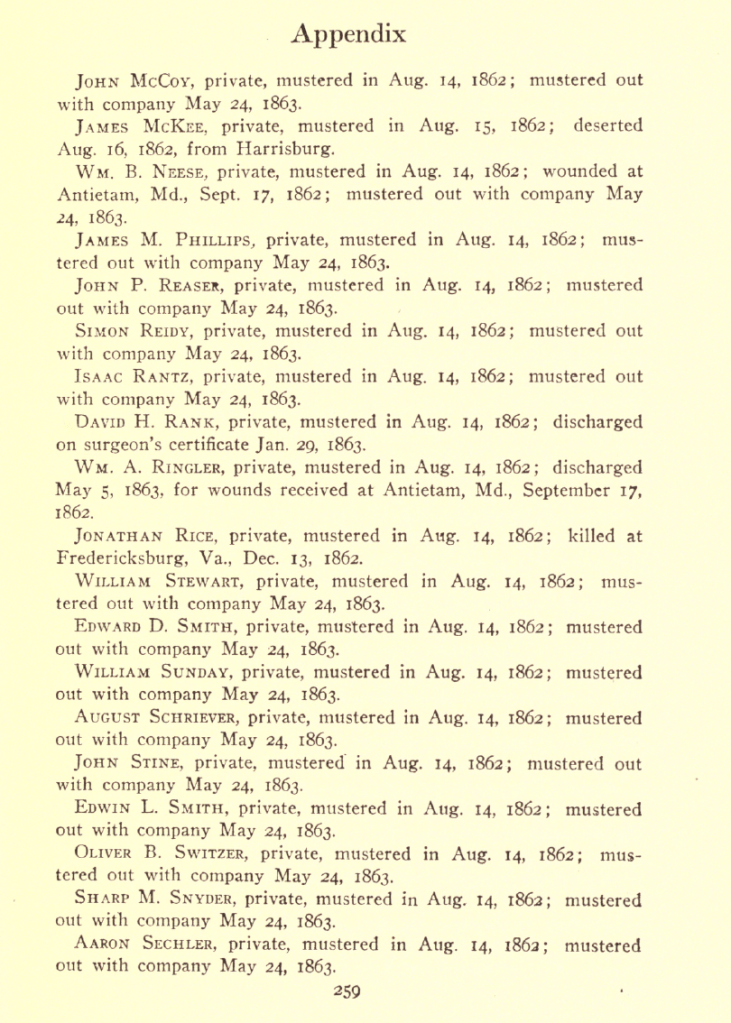

The body of the book is about 250 pages, followed by an appendix which lists all of the members of the PA 132nd, including our ancestor, Aaron Sechler.

So, amazingly, we have a near-first-hand account of most of what our second great grandfather, Aaron Sechler, did and endured for 10 months during the first half of the Civil War.

Previously, I had been confused by the fact that Aaron joined the regiment only a month before the Battle of Antietam, which scarcely seems sufficient time to organize a regiment, let alone train, outfit and transport them to the site of the biggest battle to-date of the war. Hitchcock explains that this was indeed the case for everyone in the regiment, including its officers. Soldiers were recruited in Pennsylvania in mid-August and underwent brief training in Washington DC before marching up through Maryland, camping in Rockville and (recently liberated) Frederick along the way. For most of the commissioned officers and enlisted troops, this was their first wartime assignment.

By the time they crossed South Mountain (midway between Frederick and Antietam), the PA 132nd was on the heels of Rebel forces. They just caught the tail-end of the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, giving them their first views of the aftermath of combat.

By the evening of September 16, they were in Keedysville, just a couple miles from Antietam. Hitchcock narrates…

NEVER did day open more beautiful. We were astir at the first streak of dawn. We had slept, and soundly too, just where nightfall found us under the shelter of the hill near Keedysville. No reveille call this morning. Too close to the enemy. Nor was this needed to arouse us. A simple call of a sergeant or corporal and every man was instantly awake and alert. All realized that there was ugly business and plenty of it just ahead. This was plainly visible in the faces as well as in the nervous, subdued demeanor of all. The absence of all joking and play and the almost painful sobriety of action, where jollity had been the rule, was particularly noticeable.

Before proceeding with the events of the battle, I should speak of the “night before the battle,” of which so much has been said and written. My diary says that Lieutenant-Colonel Wilcox, Captain James Archbald, Co. I, and I slept together, sharing our blankets; that it rained during the night; this fact, with the other, that we were close friends at home, accounts for our sharing blankets. Three of us with our gum blankets could so arrange as to keep fairly dry, notwithstanding the rain.

The camp was ominously still this night. We were not allowed to sing or make any noise, nor have any fires–except just enough to make coffee for fear of attracting the fire of the enemies batteries. But there was no need of such an inhibition as to singing or frolicking, for there was no disposition to indulge in either. Unquestionably, the problems of the morrow were occupying all breasts. Letters were written home many of them “last words”–and quiet talks were had, and promises made between comrades. Promises providing against the dreaded possibilities of the morrow. “if the worst happens, Jack” “Yes, Ned, send word to mother and to —–, and these; she will prize them,” and so directions were interchanged that meant so much.

I can never forget the quiet words of Colonel Oakford, as he inquired very particularly if my roster of the officers and men of the regiment was complete, for, said he, with a smile, “We shall not all be here to-morrow night.”

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

The morning of September 17, they made their way across the Antietam River to the site of the battle..

Reaching the top of the knoll we were met by a terrific volley from the rebels in the sunken road down the other side, not more than one hundred yards away, and also from another rebel line in a corn-field just beyond. Some of our men were killed and wounded by this volley. We were ordered to lie down just under the top of the hill and crawl forward and fire over, each man crawling back, reloading his piece in this prone position and again crawling forward and firing. These tactics undoubtedly saved us many lives, for the fire of the two lines in front of us was terrific. The air was full of whizzing, singing, buzzing bullets. Once down on the ground under cover of the hill, it required very strong resolution to get up where these missiles of death were flying so thickly, yet that was the duty of us officers, especially us of the field and staff. My duty kept me constantly moving up and down that whole line.

On my way back to the right of the line, where I had left Colonel Oakford, I met Lieutenant-Colonel Wilcox, who told me the terrible news that Colonel Oakford was killed. Of the details of his death, I had no time then to inquire. We were then in the very maelstrom of the battle. Men were falling every moment. The horrible noise of the battle was incessant and almost deafening. Except that my mind was so absorbed in my duties, I do not know how I could have endured the strain. Yet out of this pandemonium memory brings several remarkable incidents. They came and went with the rapidity of a quickly revolving kaleidoscope. You caught stupendous incidents on the instant, and in an instant they had passed.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

A later passage in the description seems to explain the mid-day change in position of the regiment that was shown in the National Park Service’s hourly maps. It was in direct response to a threatened out-flanking maneuver from Rebel forces…

Another incident occurred during the time we were under fire. My attention was arrested by a heavily built general officer passing to the rear on foot. He came close by me and as he passed he shouted “You will have to get back. Don’t you see yonder line of rebels is flanking you?” I looked in the direction he pointed, and, sure enough, on our right and now well to our rear was an extended line of rebel infantry with their colors flying, moving forward almost with the precision of a parade. They had thrown forward a beautiful skirmish line and seemed to be practicality masters of the situation. My heart was in my mouth for a couple of moments, until suddenly the picture changed, and their beautiful line collapsed and went back as if the d…l was after them. They had run up against an obstruction in a line of the “boys in blue” and many of them never went back. This general officer who spoke to me, I learned, was Major-General Richardson, commanding the First Division, then badly wounded, and who died a few hours after.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

By nightfall, the fighting had died down. The regiment spent several more days at the battlefield. Hitchcock notes that it wasn’t until the day after the fighting when they began receiving praise for their performance that any of them had any idea of the overall picture of what happened on September 17, how well they had done, or even learned that the battle had stated to take on the name “Antietam”.

In the days that followed, the regiment was dispatched to Harper’s ferry, about 10 miles southeast. It was a period of relative calm…

We marched through the quaint old town of Harper’s Ferry, whose principal industry had been the government arsenal for the manufacture of muskets and other army ordnance. These buildings were now a mass of ruins, and the remainder of the town presented the appearance of a plucked goose, as both armies had successively captured and occupied it. We went into camp on a high plateau back of the village known as Bolivar Heights. The scenic situation at Harper s Ferry is remarkably grand. The town is situated on the tongue or fork of land at the junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. From the point where the rivers join, the land rises rapidly until the summit of Bolivar Heights is reached, several hundred feet above the town, from which a view is had of one of the most lovely valleys to be found anywhere in the world–the Shenandoah Valley. Across the Potomac to the east and facing Harper s Ferry rises Maryland Heights, a bluff probably a thousand feet high, while across the Shenandoah to the right towers another precipitous bluff of about equal height called Loudon Heights. Both of these bluffs commanded Bolivar Heights and Harper s Ferry.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

During its existence, the PA 132nd fought two more major battles, both in Virginia–the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 11-15, 1862, and the Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 through May 6, 1863. While Antietam was generally seen as a draw between North and South, both Fredericksburg and Falmouth were both decisive victories for the South and, judging from Hitchcock’s descriptions, even more perilous to the men of 132nd. The following is from Hitchcock’s narration of Fredericksburg, where the PA 132nd found itself in the center of the town, surrounded on three sides by Rebel forces entrenched in the overlooking hills…

REACHING the place in the rear of that railroad embankment, where I had left the brigade, I found it had just gone forward in line of battle, and a staff officer directed me to bring the rest of the regiment forward under fire, which I did, fortunately getting them into their proper position. The line was lying prone upon the ground in that open field and trying to maintain a fire against the rebel infantry not more than one hundred and fifty yards in our front behind that stone wall. We were now exposed to the fire of their three lines of infantry, having no shelter whatever. It was like standing upon a raised platform to be shot down by those sheltered behind it. Had we been ordered to fix bayonets and charge those heights we could have understood the movement, though that would have been an impossible undertaking, defended as they were. But to be sent close up to those lines to maintain a firing-line without any intrenchments or other shelter, if that was its purpose, was simply to invite wholesale slaughter without the least compensation. It was to attempt the impossible, and invite certain destruction in the effort. On this interesting subject I have very decided convictions, which I will give later on.

Proceeding now with my narrative, we were evidently in a fearful slaughter-pen. Our men were being swept away as by a terrific whirlwind. The ground was soft and spongy from recent rains, and our faces and clothes were bespattered with mud from bullets and fragments of shells striking the ground about us, whilst men were every moment being hit by the storm of projectiles that filled the air. In the midst of that frightful carnage a man rushing by grasped my hand and spoke. I turned and looked into the face of a friend from a distant city. There was a glance of recognition and he was swept away. What his fate was I do not know.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

Hitchcock’s “decided convictions” boil down to the view (supported several pages of evidence and logical reasoning) that the Union’s role in the Battle of Fredericksburg was a total fiasco, driven by grave errors that came from high in the chain of command.

The Battle of Fredericksburg is the site of an incident which was to become the core how the PA 132nd saw itself and its role in history. Recalling the monument to the 132nd which was built at Antietam, a close look reveals that the standard holding the flags of the regiment has been shot off, the missing section lying behind the feet of the soldier holding it.

The soldier in the monument is, in fact, Major Frederick Hitchcock himself. It was he who was holding the flags in the Battle of Fredericksburg, having picked them up from another soldier of the 132nd who had just been killed. Immediately after, a shell exploded nearby, knocking Hitchcock unconscious. He regained consciousness a few minutes later amongst a pile of dead soldiers and staggered/ran back to the cover of his comrades, barely escaping with his life.

The flags, however, could not be found in the days following the battle. They eventually turned up in the possession of another regiment, and it was discovered that false stories had been circulated about the performance of the PA 132nd at Fredericksburg–stories suggesting a less-than-valiant performance. The entire 132nd was enraged that such stories had made it into the record, and they immediately appealed to higher authorities. The final judgement of the authorities was to recognize that the stories were false, completely exonerating the regiment. Their cherished flags were returned to them.

This story became part of the legend of the PA 132nd, symbolizing the extreme pride they took in their efforts on the battlefield. When Hitchcock eventually wrote the story into his book, the legend grew stronger. This was the time near the turn of the century that Civil War veterans groups were most active in constructing monuments to their war efforts. The statue was dedicated about the same time as the book was formally published (1904), and the statue, book, and deeds of the regiment all became synonymous with each other.

In the months between the major battles that the 132nd fought, there was plenty of down-time. The regiment spent winter of 1862-1863 camped near Falmouth, Virginia. Hitchcock goes into great detail on daily life during these times, including this description of the troops’ efforts to entertain themselves by putting on a steeple chase…

The chief event of the day and the wind-up was a hurdle and ditch race, open to officers only. Hurdles and ditches alternated the course at a distance of two hundred yards, except at the finish, where a hurdle and ditch were together, the ditch behind the hurdle. Such a race was a hare-brained performance in the highest degree; but so was army life at its best, and this was not out of keeping with its surroundings. Excitement was what was wanted, and this was well calculated to produce it.

The hurdles were four and five feet high and did not prove serious obstacles to the jumpers, but the ditches, four and five feet wide and filled with water, proved a bete noir to most of the racers. Some twenty-five, all young staff-officers, started, but few got beyond the first ditch. Many horses that took the hurdle all right positively refused the ditch. Several officers were dumped at the first hurdle, and two were thrown squarely over their horses heads into the first ditch, and were nice looking specimens as they crawled out of that bath of muddy water. They were unhurt, however, and remounted and tried it again, with better success.

The crowning incident of the day occurred at the finish of this race at the combination hurdle and ditch. Out of the number who started, only three had compassed safely all the hurdles and ditches and come to the final leap. The horses were about a length apart each. The first took the hurdle in good shape, but failed to reach the further bank of the ditch and fell over sideways into it, carrying down his rider. Whilst they were struggling to get out, the second man practically repeated the performance and fell on the first pair, and the rear man, now unable to check his horse, spurred him over, only to fall on the others. It was a fearful sight for a moment, and it seemed certain that the officers were killed or suffocated in that water, now thick with mud. But a hundred hands were instantly to the rescue, and in less time than it takes to tell it all were gotten out and, strange to say, the horses were unhurt and only one officer seriously injured, a broken leg only to the bad for the escapade. But neither officers nor horses were particularly handsome as they emerged from that ditch. The incident can be set down as a terrific finale to this first and last army celebration of St. Patricks day.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

In early May, the calm came to an abrupt end as forces emerged from the winter and engaged at Battle of Chancellorsville, a week of slogging through dense forests, often with no idea of who was where on either side. The 132nd went through several situations where they barely escaped enemy forces moving on parallel paths to their own.

And then, suddenly, it was time to go home. The 132nd’s tour of duty had already been extended by a month, due to the critical situation surrounding the Chancellorsville battles, with little complaint. The regiment received orders to return to Washington and soon boarded trains back to Harrisburg.

Amid the joyous homecomings, amazingly, there was strong sentiment to keep the unit going, that their work was not yet finished. Hitchcock narrates the following tale…

I should mention a minor incident that occurred during our stay in Harrisburg preparing for muster out. A large number of our men had asked me to see if I could not get authority to re-enlist a battalion from the regiment. I was assured that three-fourths of the men would go back with me, provided they could have a two weeks furlough. I laid the matter before Governor Curtin. He said the government should take them by all means; that here was a splendid body of seasoned men that would be worth more than double their number of new recruits; but he was without authority to take them, and suggested that I go over to Washington and lay the matter before the Secretary of War. He gave me a letter to the latter and I hurried off. I had no doubt of my ability to raise an entire regiment from the great number of nine-months men now being discharged. I repaired to the War Department, and here my troubles began. Had the lines of sentries that guarded the approach to the armies in the field been half as efficient as the cordon of flunkies that barred the way to the War Office, the former would have been beyond the reach of any enemy. At the entrance my pedigree was taken, with my credentials and a statement of my business. I was finally permitted to sit down in a waiting-room with a waiting crowd. Occasionally a senator or a congressman would break the monotony by pushing himself in whilst we cultivated our patience by waiting. Lunch time came and went. I waited. Several times I ventured some remarks to the attendant as to when I might expect my turn to come, but he looked at me with a sort of far-off look, as though I could not have realized to whom I was speaking. Finally, driven to desperation, after waiting more than four hours, I tried a little bluster and insisted that I would go in and see somebody. Then I was assured that the only official about the office was a Colonel , acting assistant adjutant-general. I might see him.

“Yes,” I said, “let me see him, anybody!”

I was ushered into the great officials presence. He was a lieutenant-colonel, just one step above my own rank. He was dressed in a faultless new uniform. His hair was almost as red as a fresh red rose and parted in the middle, and his pose and dignity were quite worthy of the national snob hatchery at West Point, of which he was a recent product.

“Young man,” said he, with a supercilious air, “what might your business be?”

I stated that I had brought a letter from His Excellency, Governor Curtin, of Pennsylvania, to the Secretary of War, whom I desired to see on important business.

“Where is your letter, sir?”

“I gave it up to the attendant four hours ago, who, I supposed, took it to the Secretary.”

“There is no letter here, sir! What is your business? You cannot see the Secretary of War.”

I then briefly stated my errand. His reply was, “Young man, if you really desire to serve your country, go home and enlist.”

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

Which is exactly what Aaron Sechler and presumably a great number of his fellow soldiers of the PA 132nd did. Such was their commitment to each other and to the war effort. Aaron’s next tour of duty was with the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry and went from February 1864 to August 1865, about twice the length of his first tour. It took him deep into the South as the war ground to its completion. We probably won’t find a book that covers this period of Aaron Sechler’s life as well as Hitchcock’s book describes the prior period.

I believe this situation not to be terribly different from what we often see today, with soldiers who sign up for repeated tours of duty in Iraq or Afghanistan, because of feelings that the job is not finished and because there is something about the comradeship of the battlefield that does not compare to anything in the daily world.

To close this chapter, I turn once more to Colonel Hitchcock, whose final reflections on the Pennsylvania 132nd Infantry Regiment far surpass anything I could come up with…

A word now of the personnel of the One Hundred and Thirty-second Regiment and I am done. Dr. Bates, in his history of the Pennsylvania troops, remarks that this regiment was composed of a remarkable body of men. This judgment must have been based upon his knowledge of their work. Every known trade was represented in its ranks. Danville gave us a company of iron workers and merchants, Catawissa and Bloomsburg, mechanics, tradesmen, and farmers. From Mauch Chunk we had two companies, which included many miners. From Wyoming and Bradford we had three companies of sturdy, intelligent young farmers intermingled with some mechanics and tradesmen. Scranton, small as she was then, gave us two companies, which was scarcely a moiety of the number she sent into the service. I well remember how our flourishing Young Men s Christian Association was practically suspended because its members had gone to the war, and old Nay Aug Hose Company, the pride of the town, in which many of us had learned the little we knew of drill, was practically defunct for want of a membership which had “gone to the war.” Of these two Scranton companies, Company K had as its basis the old Scranton City Guard, a militia organization which, if not large, was thoroughly well drilled and made up of most excellent material. Captain Richard Stillwell, who commanded this company, had organized the City Guard and been its captain from the beginning. The other Scranton company was perhaps more distinctively peculiar in itspersonnel than either of the other companies. It was composed almost exclusively of Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad shop and coal men, and was known as the Railroad Guards. In its ranks were locomotive engineers, firemen, brakemen, trainmen, machinists, telegraph operators, despatchers, railroad-shop men, a few miners, foremen, coal-breaker men, etc. Their captain, James Archbald, Jr., was assistant to his father as chief engineer of the road, and he used to say that with his company he could survey, lay out, build and operate a railroad. The first sergeant of that company, George Conklin, brother of D. H. Conklin, chief despatcher (sic) of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western, and his assistant, had been one of the first to learn the art of reading telegraph messages by ear, an accomplishment then quite uncommon. His memory had therefore been so developed that after a few times calling his company roll he dispensed with the book and called it alphabetically from memory. Keeping a hundred names in his mind in proper order we thought quite a feat. Forty years later, at one of our reunions, Mr. Conklin, now superintendent of a railroad, was present. I asked him if he remembered calling his company roll from memory.

“Yes,” said he, “and I can do it now, and recall every face and voice,” and he began and rattled off the names of his roll. He said sometimes in the old days the boys would try to fool him by getting a comrade to answer for them, but they could never do it, he would detect the different voice instantly.

War From The Inside, The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion 1862-1863 by Colonel Frederick L. Hitchcock, 1904.

What an excellent description of the events that occurred over one hundred and fifty years ago. Such brave men and heroic deeds must never be forgotten.

LikeLike