The war was coming to an end, and President Lincoln was looking ahead to rebuilding the country. He and/or his Secretary of State William Seward noticed Edward and named him to the post of United Status Consul to CheeFoo China. His Civil War service record combined with his maritime experience and previous trip to China must have made him an ideal candidate in a time when men to fill any position were in short supply.

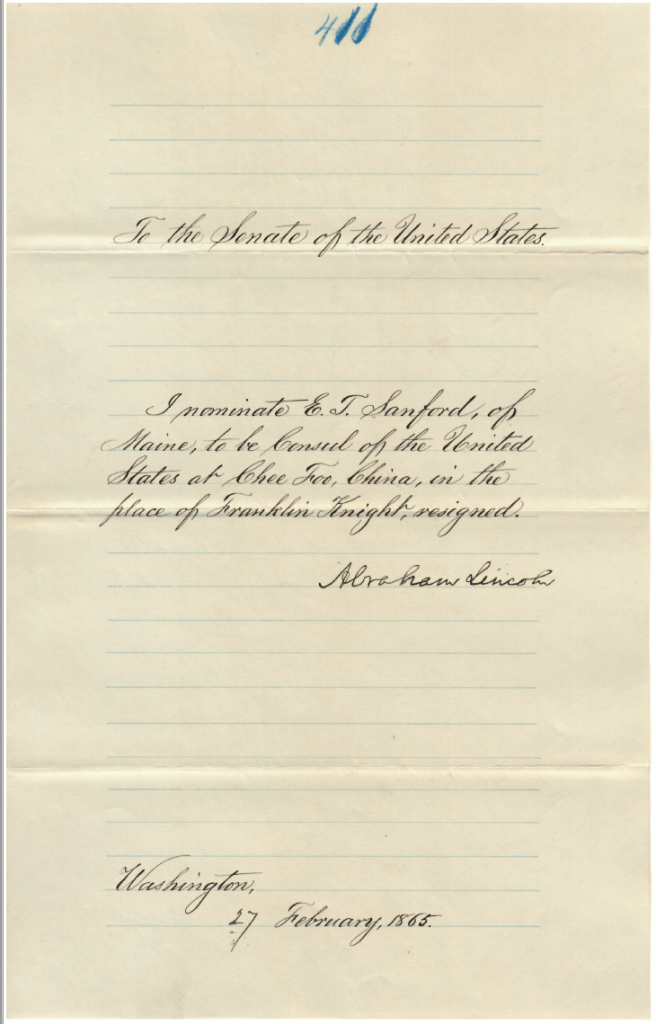

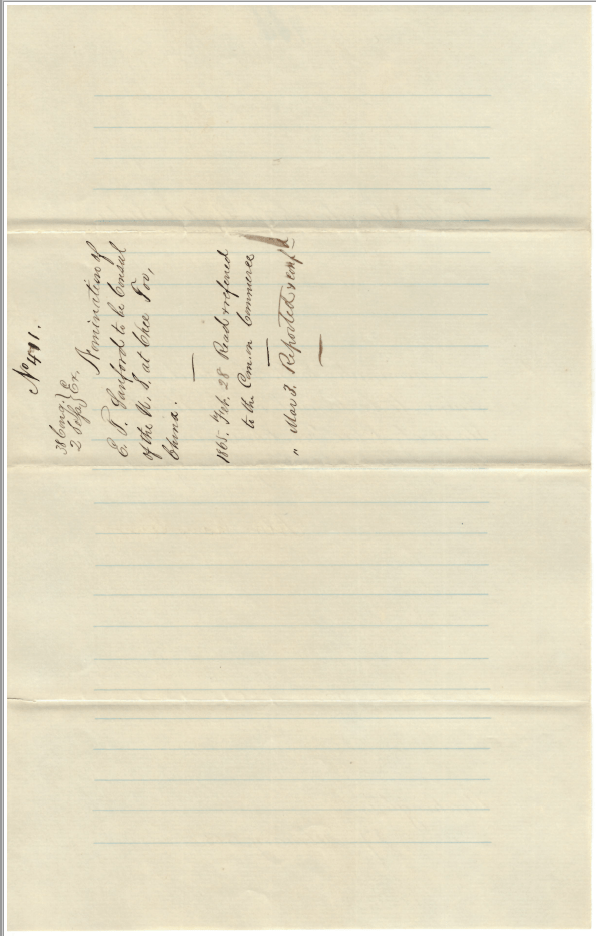

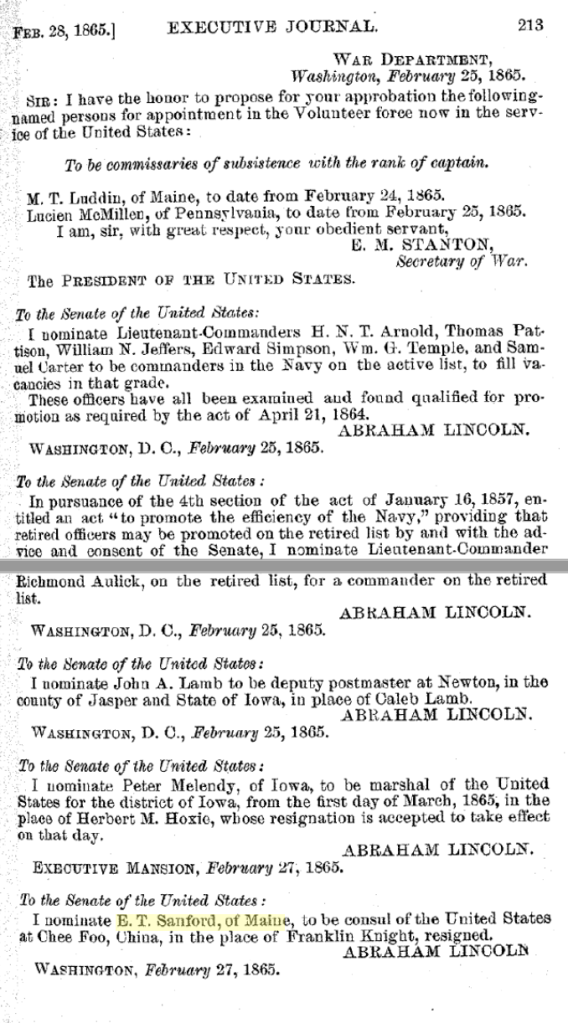

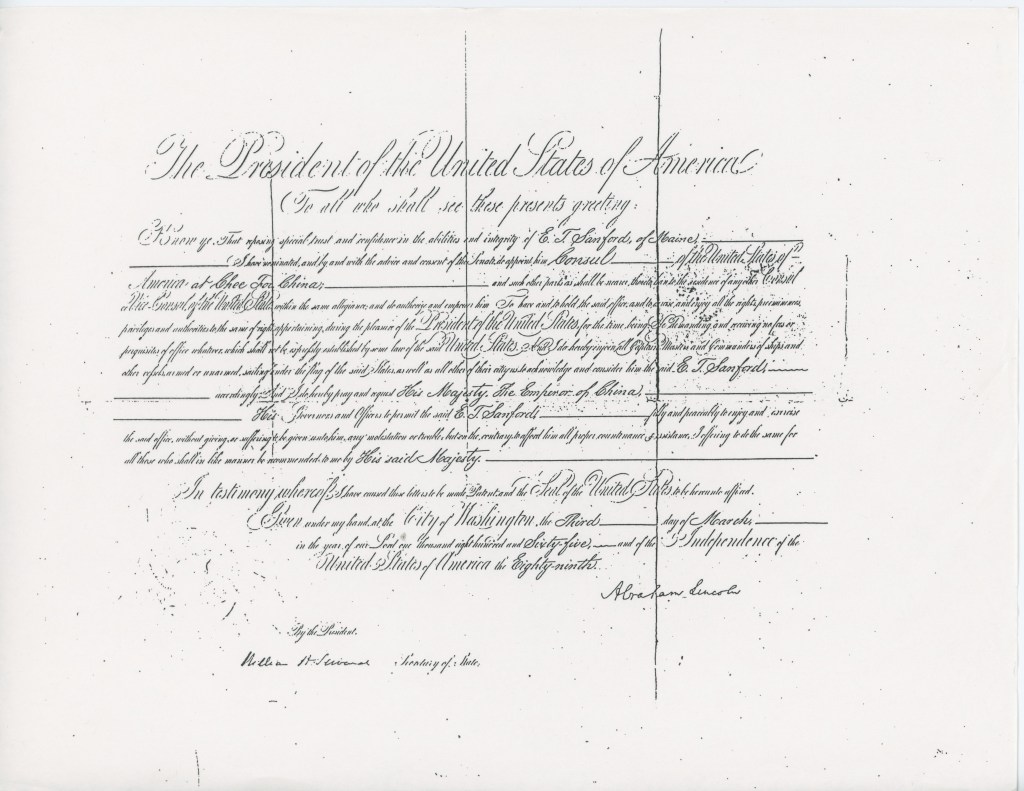

Lincoln nominated Sandford to the post on February 27, 1865, signing a simple statement on note paper, written-out by an aide.

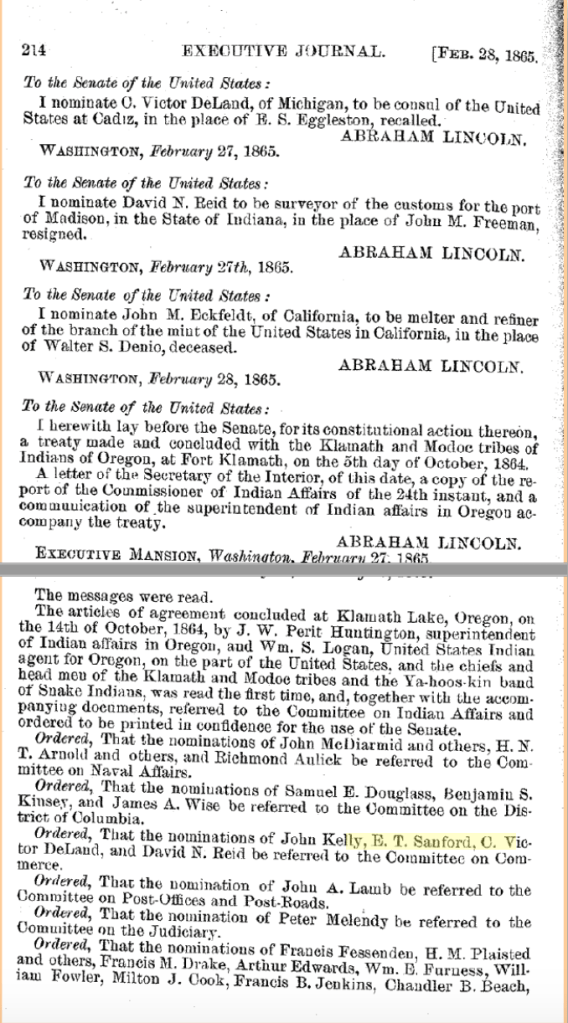

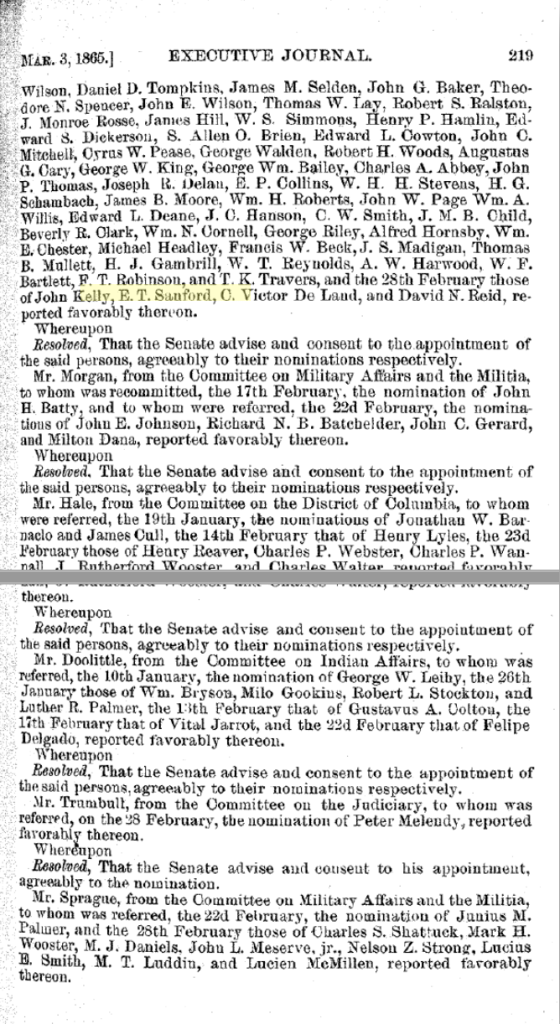

Sandford’s nomination quickly moved through the United States Senate where perhaps there was some institutional memory of Senator Nathan Sanford from New York, who had retired 34 years earlier, a subject for a future post. Although Nathan had adopted a different spelling of the last name, Edward was his cousin (several times removed). The nomination moved quickly through the Senate, being confirmed within a week.

Lincoln’s formal letter appointing Edward to the post is dated March 3, 1865. The framed original of this letter used to hang in the home office of our grandfather Joe in Ontario, California.

The National Archives annex in College Park Maryland has records of Edward’s foreign service correspondence saved on microfilm. Most of the correspondence is addressed to Secretary of State William Seward.

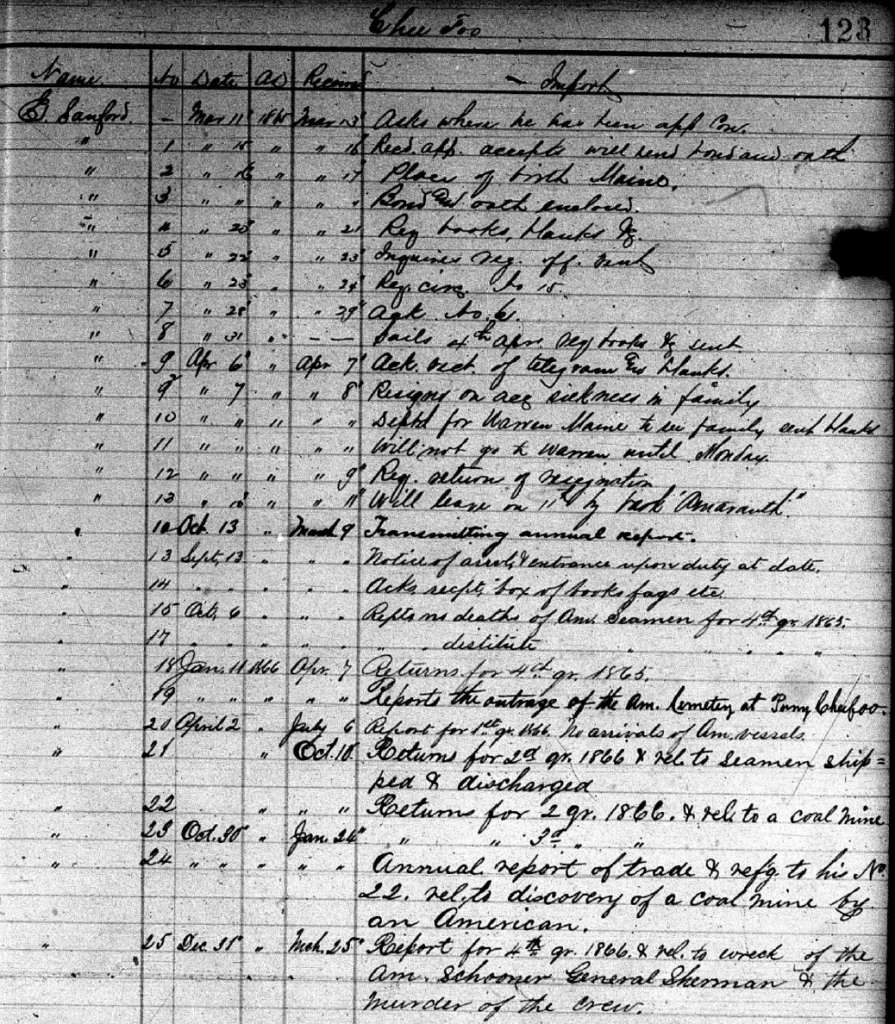

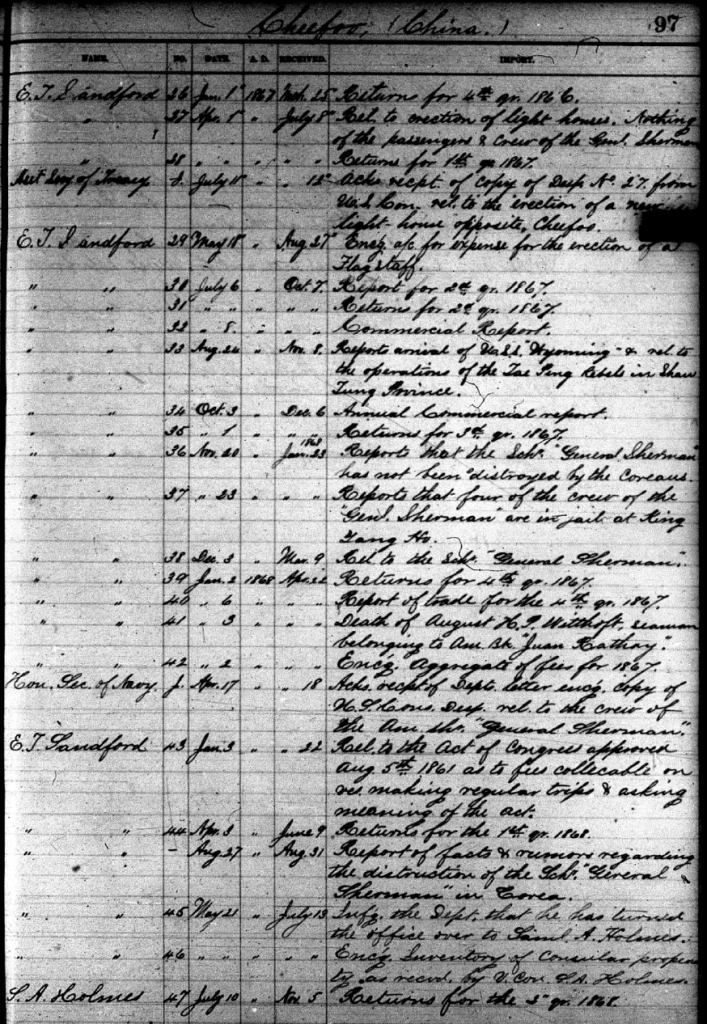

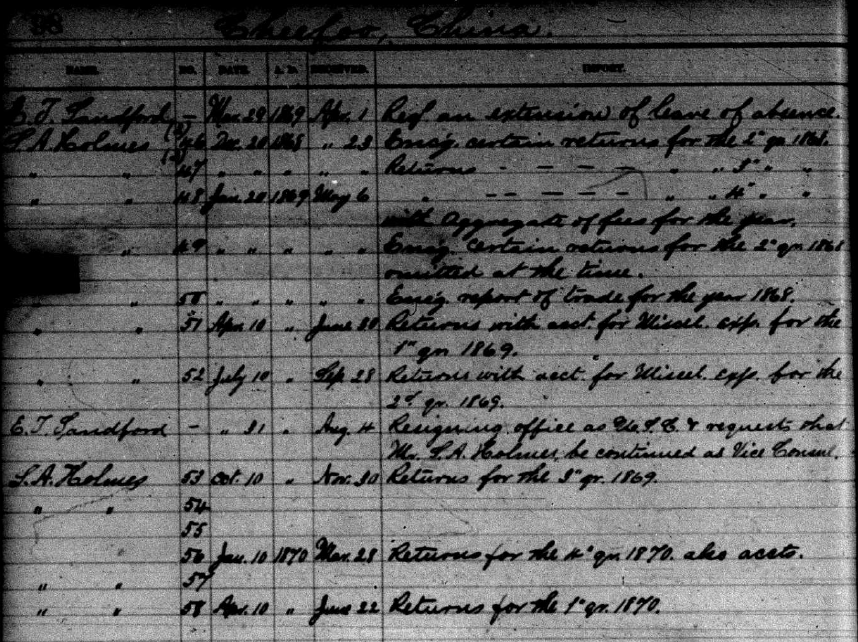

A log of the correspondence (I believe this is an actual Government log from the 1860s, not something created later by an archivist) records over 50 entries (there are a few clerical mistakes in the numbering system so a few of the log entry numbers are used more than once) between March 11, 1865 and July 31, 1869. Separate columns record the date the correspondence was sent and the date it was received in Washington–for correspondence originating in China, these dates can be several months apart.

United States government interaction with China was in its infancy. From earlier parts of the log, it is clear that Edward was only the second person to be assigned to this particular post.

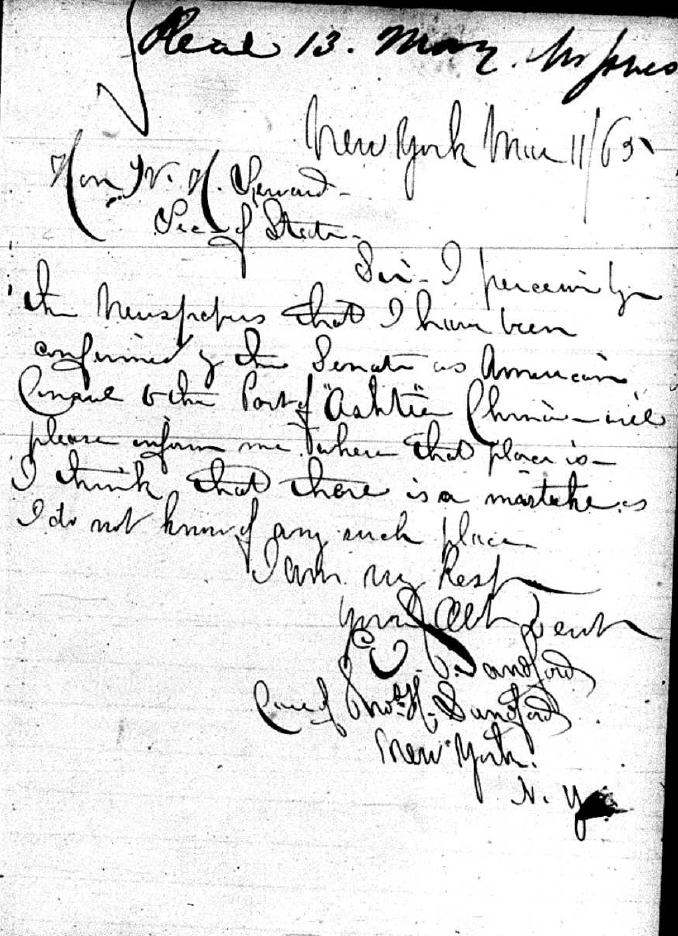

Edward seems to get off to a shaky start with his new job–His nomination and appointment seem to take him off-guard, and it is not clear how he first learned of it. In his first letter, dated March 11, 1865 he proclaims to Seward, referring to CheeFoo, “I think that there is a mistake as I do not know of any such place.” Even though he has already had a lifetime of experiences, Edward is only 24 years old at this time. Seward, in his 60’s, if he ever saw this letter, must have rolled his eyes and turned to an aide and asked him to get this kid straightened out.

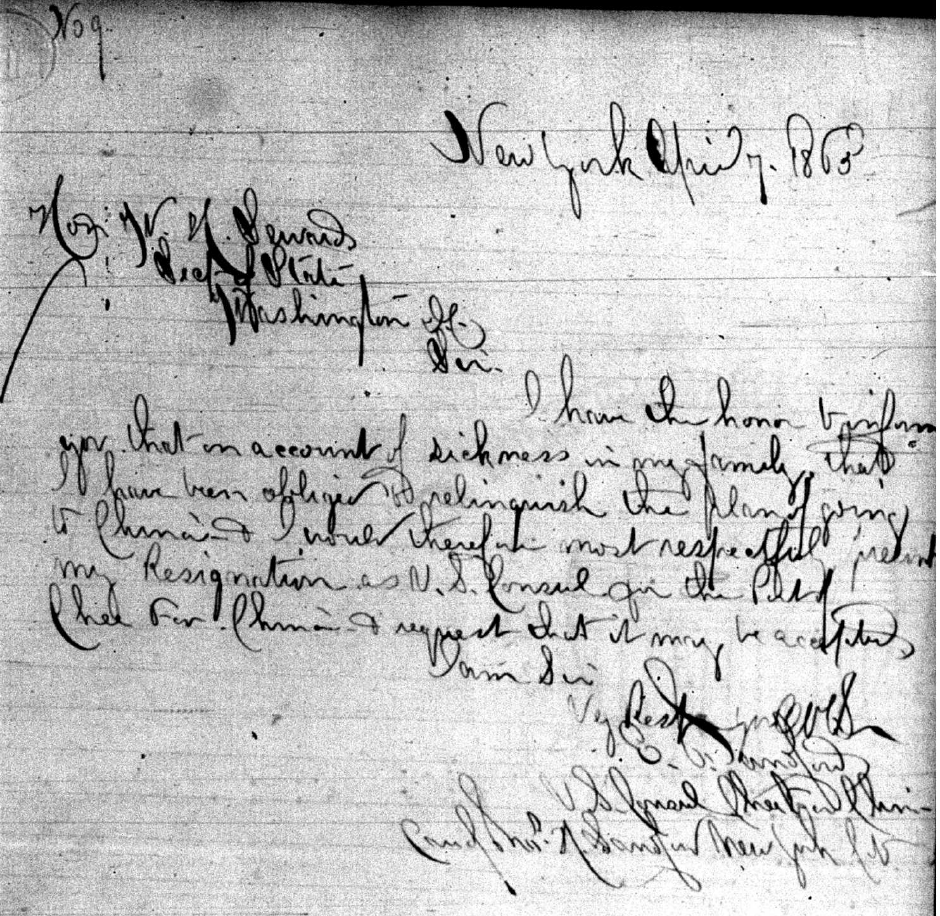

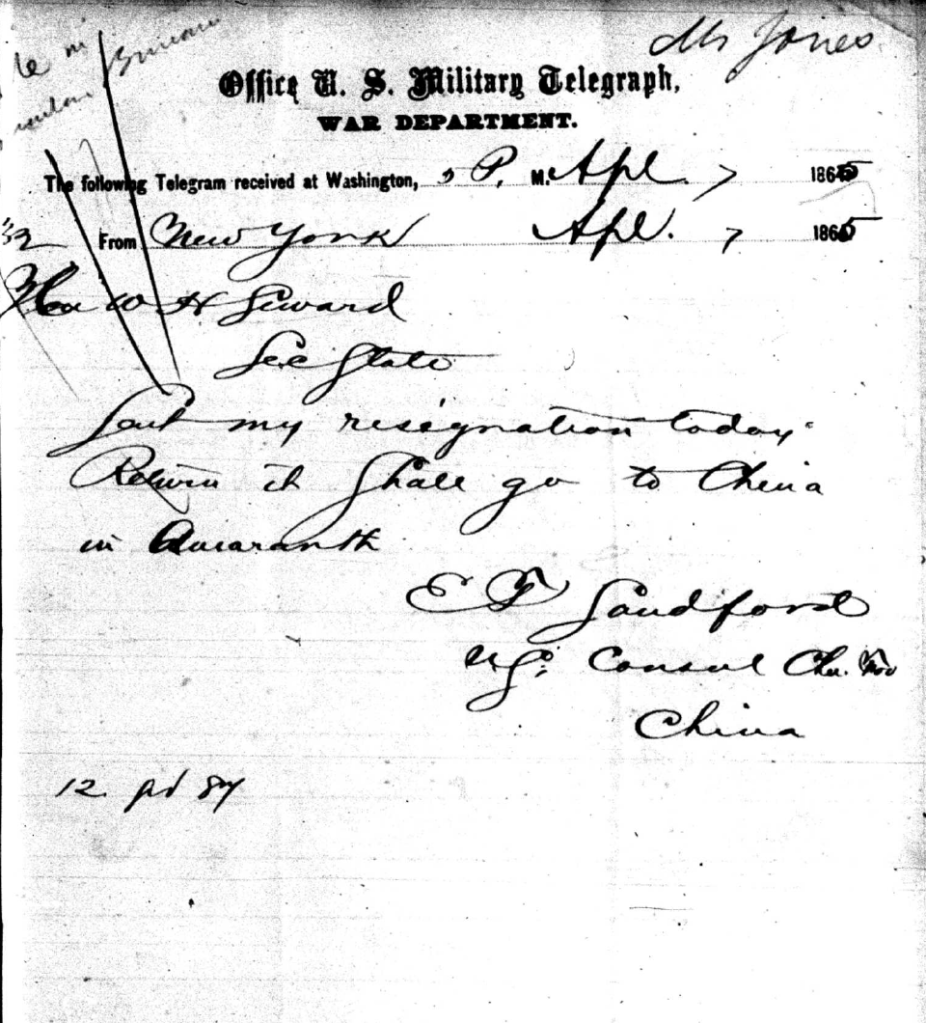

There is a series of letters in March dealing with administrative affairs, then on April 7 Edward sends a letter of resignation due to an illness in his family. He seems to regret this decision almost immediately–the same day he sends a telegram to Seward asking him to ignore the resignation. This is quickly followed by other awkward letters where he provides status of his trip back to his home in Warren to check on the situation with the illness, in each letter he has to reiterate his previous communications rescinding his resignation.

It is not clear who the family illness referred to. His wife, Sarah, was sick much of her later life, but this would be the earliest reference to her being ill, if it was her. Edward’s mother had died a in 1847 and his father would live to 1898.

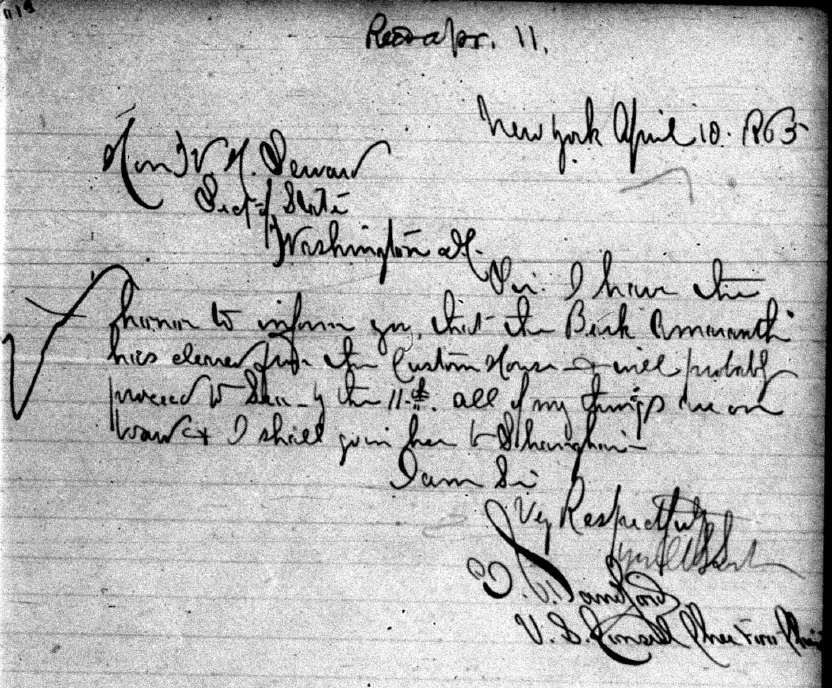

Somehow Edward got his affairs in order quickly. In an April 10 letter he states that his possessions are loaded on a ship that is preparing to sail.

Lincoln was assassinated April 15, so Edward must have sailed just a few days before and received the news at a port along the way. Based on information from Edward’s previous trip to China, I assume he took the route around South America (the Suez Canal would not open until 1869), so there would have been ports along the U.S. east cost. I found no correspondence that spoke of the assassination. It seems that the norm of the time was that people stayed in their Government posts across administrations, more than would be the case today—both Edward and Seward stayed on the job under the new president Andrew Johnson.

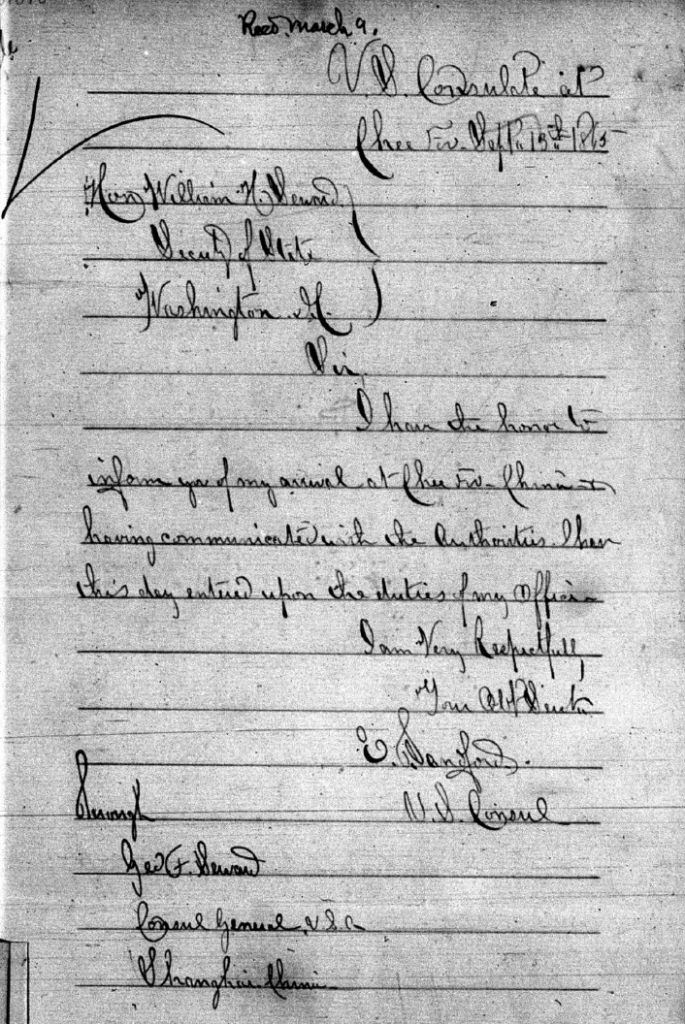

The next correspondence from Edward is dated September 13, 1865 (received in Washington March 9 of the following year) and announces his arrival and start of duties in CheeFoo. His handwriting is much improved in this short letter, so it may have dawned on him somewhere along the way that he was now in the big leagues. Edward’s handwriting slopes to the left, and can be difficult to decipher.

As Consul, Edward had a set of determined duties. Much of his correspondence over his tenure consisted of routine filings of required reports. Much of his initial correspondence, back in March 1865, dealt with him getting the instructions and sets of forms (referred to as ‘blanks’) needed to carry out his duties.

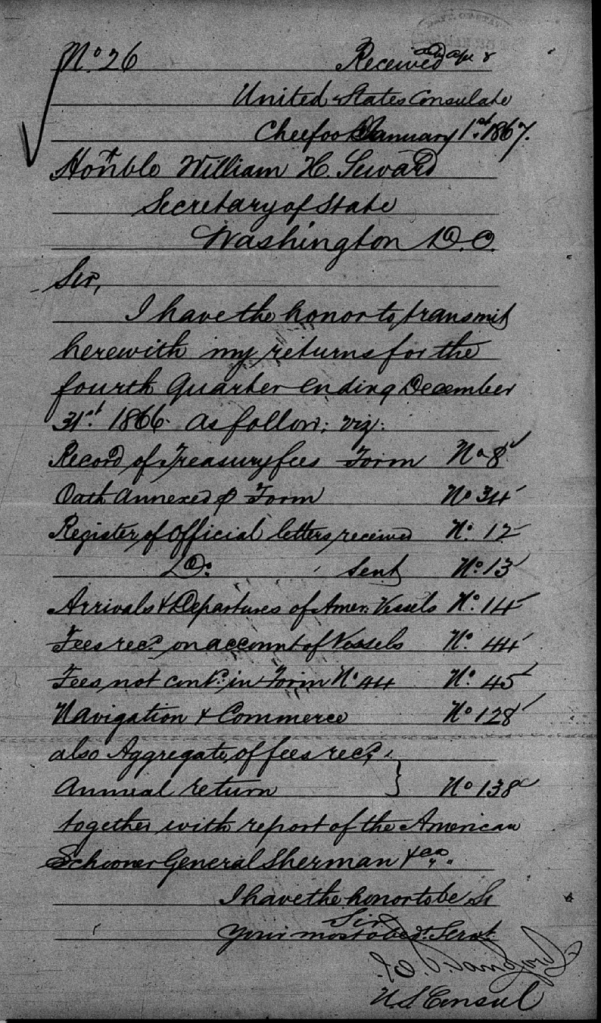

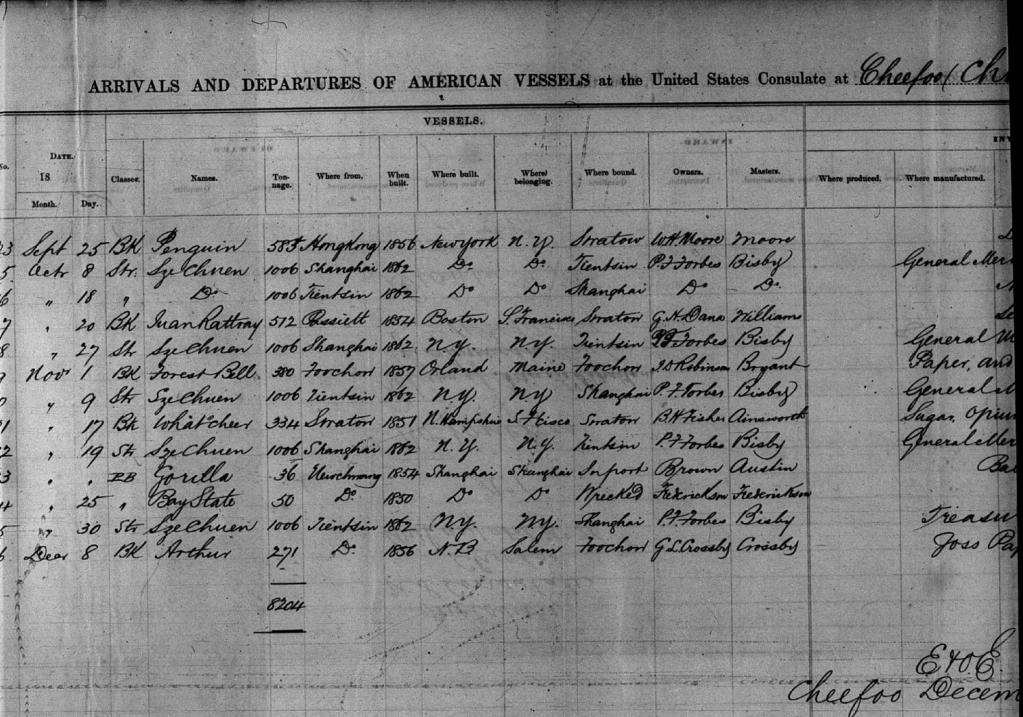

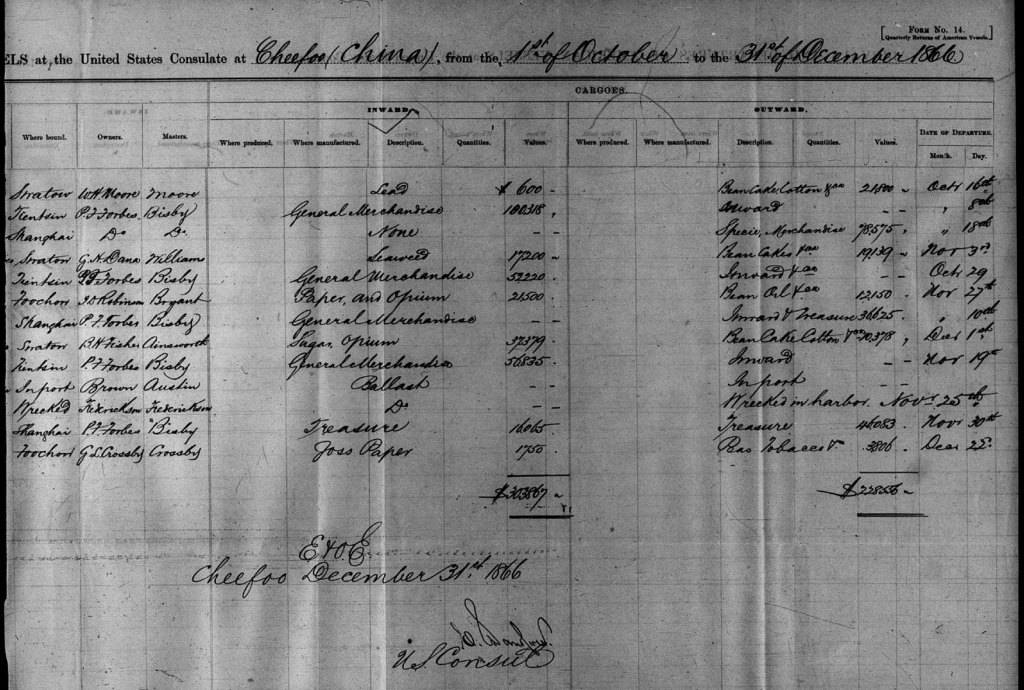

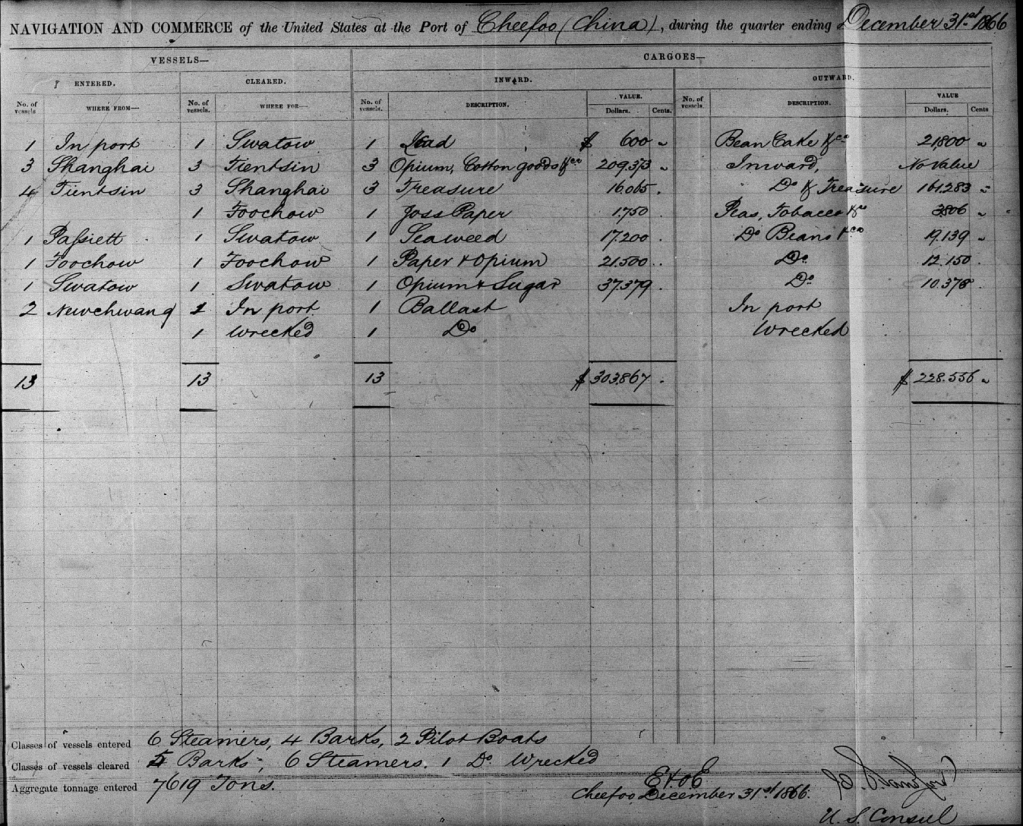

Edward’s submission of his annual report for the fourth quarter of 1866, submitted on January 1, 1867 provides examples of his day-to-day duties.

Not all of Edward’s duties in CheeFoo were dull and routine. We will continue the stories of Edward’s adventures in China in a future post.

5 thoughts on “Edward Sandford returns to China”