We’re all ghosts. We all carry, inside us, people who came before us.

Liam Callanan, The Cloud Atlas

The folder stares at me from the corner of the desk like a historical marker on a road near your house that you pass by several times a day. It’s been staring at me for 30 years.

A green hanging folder, not hanging but laid flat, less than an inch thick, with a handwritten tab enclosed in plastic, “Family Tree Stuff”. I don’t remember exactly when I started the file, probably it was created to consolidate a few items that had been accumulated in different places. Papers and documents that came mostly from my parents, at different times, glanced at briefly then set aside. Papers eventually to be accumulated in the single folder created for the purpose, I suppose, of not having to deal with them right away, but at least having the intuition that they needed to be kept somewhere. The existence of the folder ensured that for over 30 years, any new item that came my way had a place to go.

“Family Tree Stuff”, I at least knew, contained an actual handwritten family tree diagram made by my mother’s father a half century ago. I also knew that there was some kind of document on my father’s side with information that would allow the creation of a tree for that side of the family. The simplistic thought had been kicking around for decades that it would be easy enough to put the two trees together and complete my generational duties to leave a tree for the next generation. I think there was also a vague awareness of the emergence of on-line genealogical resources, combined with the thinking that all one had to do was to tap into on-line family trees created by other distant family members and, poof, a complete tree would be there to look at and pass on to future generations. I would later learn that, while having seeds of truth, these views did not begin to capture the full reality of what was to come.

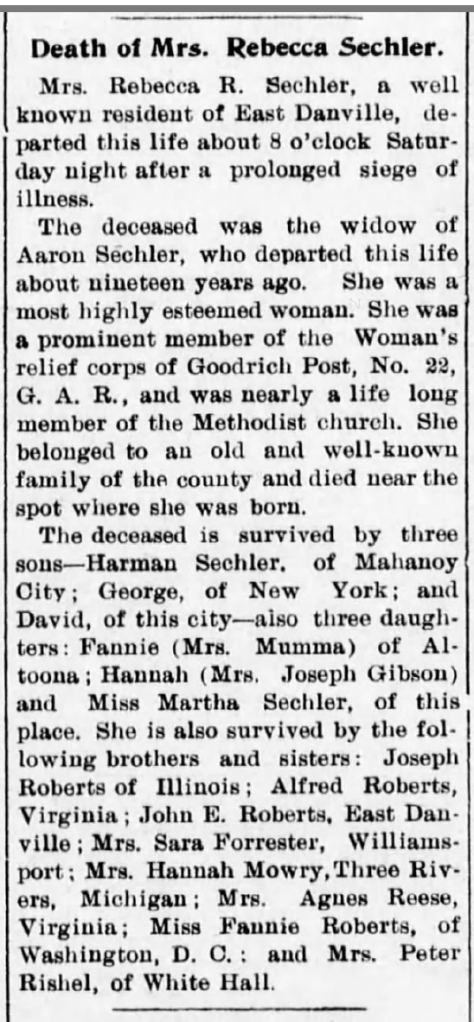

So there it sat, the folder of documents, accumulated but not acted-upon, even during late years of my father’s life when he would hint at his desire to ensure that the information be retained in the family’s consciousness. Interestingly, it is not at all clear to me that he himself had made any real efforts to delve into the available information. He would say things like “there’s chapter in a book that my siblings know about that describes our family history—I made you a copy of my copy—I think there’s a whole book somewhere that maybe Ned knows about.” He knew, of course of the stories of his own grandparents—alternately heroic, violent, and shocking. The story of his father’s father’s appointment by Abraham Lincoln to a diplomatic post in China had always been at the forefront of the family lore, but it would be for me to later discover that this paled in comparison to the events before and after this chapter in the amazing life of this man. I recall that decades earlier my father had also told me of the suicide of his mother’s father in the 1920s in southern California, but in all honesty it didn’t even stick with me exactly who this person was, let alone the context within which this story unfolded. So this, too, was a story that fell to me to rediscover.

On my mother’s side, even less information, combined with a near absence of willingness to discuss. Until my investigations began, I would not even clearly recall that her mother had grown up without a father in Brooklyn, although I do remember occasional references to this from my grandmother. Astounding that I would never actually ask her about this during her lifetime—the list of missed opportunities of which I have become aware since the beginnings of my research is mind-boggling. On this side of the family, what triggered my eventual curiosity was a much more mundane question that had occurred to me: “I know my maternal grandparents lived and met in Brooklyn; I spend time in and sort of know Brooklyn; I wonder where they lived?” The folder was still sitting on my desk when I impulsively asked my mother where they lived and the few scraps of information she revealed would eventually lead to a set of stories, equally heroic, violent, and shocking to those of my father’s family, as the other bookend on the shelf of my personal family history.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. For now, the folder sits there on the desk where I put it a couple months ago thinking that now, with retirement behind me, might be the time to figure this stuff out.

Like any journey, this one begins with a single step, the evening that I open the folder and begin reading, before long coming to the “copy of chapter in a book” that my father talked about. Some initial struggles with the standard format of genealogical documents (now second-nature), an initial flurry of names and places, Robert Sandford, Ezekiel Sandford, Hartford Connecticut, Bridgehampton Long Island, some impulsive Google searches, and … oh my God.

Entries to come will examine the lives of eight great grandparents, what came before, and what came after. They are…

- Edward Thomas Sandford from Topsham, Maine

- Annie Calderwood from St. Johnsbury, Vermont

- Henry Edson Swan from Indiana

- Mabel Tuttle from Illinois

- James Louis Hynes from Shoal Arm, Newfoundland

- Bessie Gordon from Newburgh, New York

- George Mowrer Sechler from Danville, Pennsylvania

- Laura Jane Wright from Prince Edward Island

Additionally, I will look at the lives of the four grandparents who came after…

- Edward Joseph Sandford from Twin Lakes (San Jose), California

- Margaret Swan from Mankato, Minnesota

- James Gordon Hynes from Cornwall, New York

- Ruth Sechler from Brooklyn, New York

See more about them …

Joe: We used to hike clear up to the top of Baldy, Ontario Peak.

Joe: We used to hike clear up to the top of Baldy, Ontario Peak.

Sunday April 14, 1907 was a beautiful early spring day in Washington Square Park in lower Manhattan, the park with the iconic grand arch. Late in the afternoon, hundreds of families were enjoying the last hours of their weekend. A minor jostle in a restroom quickly spiraled to a major altercation as a man named Salvatore Governale, a recent immigrant from Sicily, pulled a gun and began firing. Two shots went into the air, but a third shot hit and fatally wounded a 19 year old boy.

Sunday April 14, 1907 was a beautiful early spring day in Washington Square Park in lower Manhattan, the park with the iconic grand arch. Late in the afternoon, hundreds of families were enjoying the last hours of their weekend. A minor jostle in a restroom quickly spiraled to a major altercation as a man named Salvatore Governale, a recent immigrant from Sicily, pulled a gun and began firing. Two shots went into the air, but a third shot hit and fatally wounded a 19 year old boy.