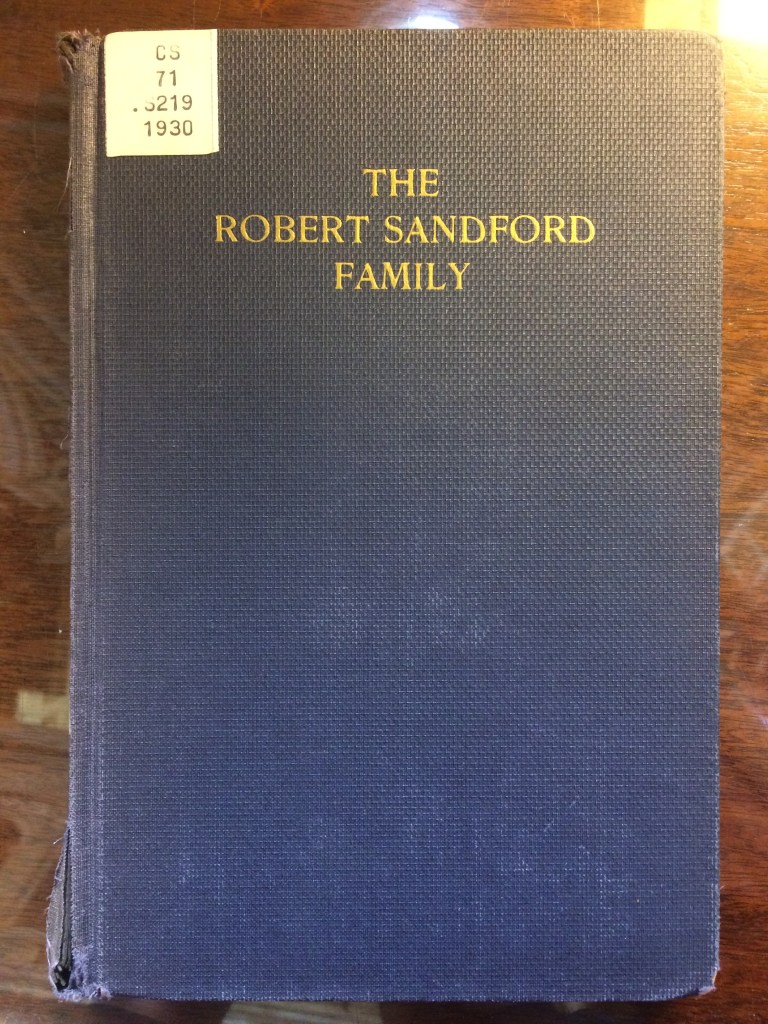

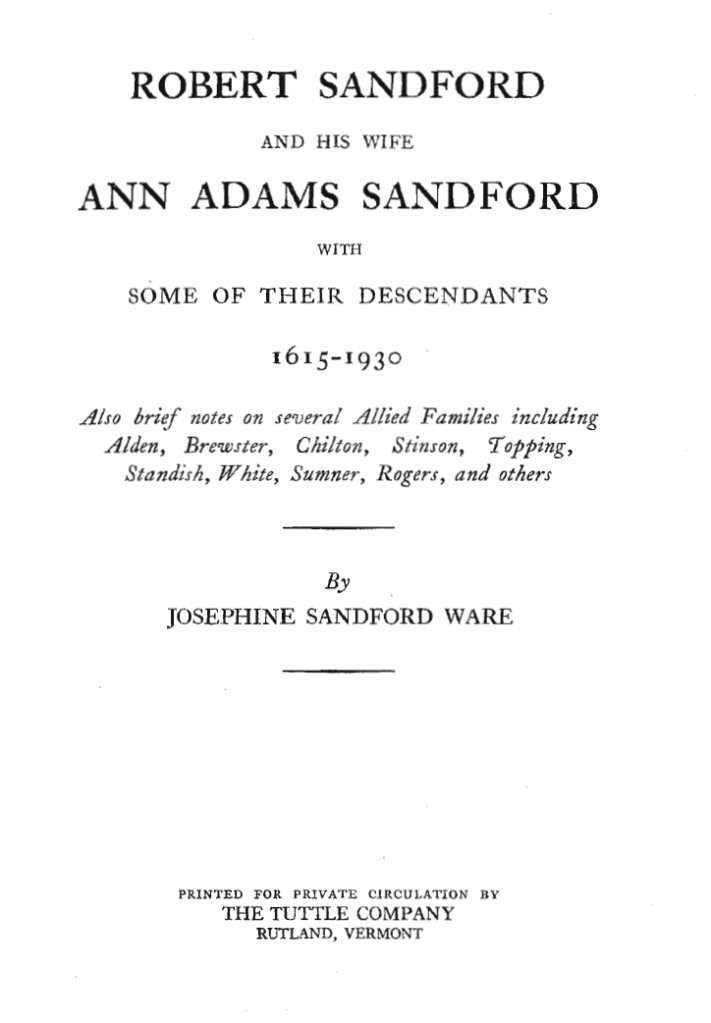

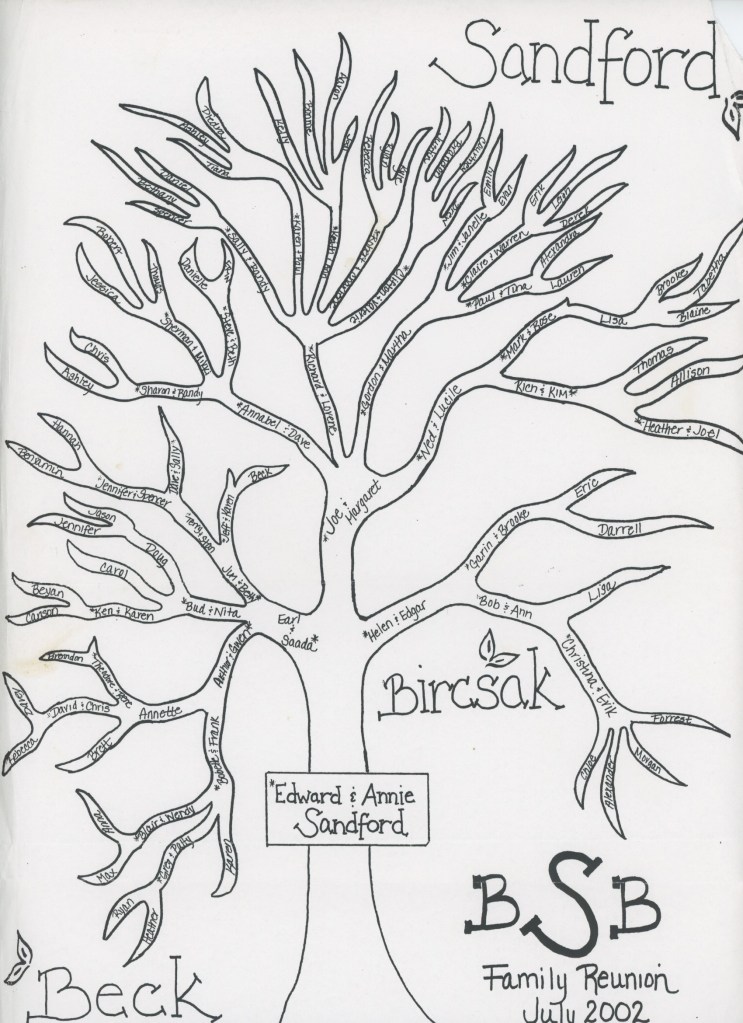

For ninety years, the primary record of the genealogy of our branch of the Sandford family has been the book Robert Sandford and His Wife Ann Adams Sandford with Some of Their Descendants, 1615-1930, written by Josephine Sandford Ware. This 85 page account has been floating around our family since its 1930 publication. It can easily be found today on the internet.

For ninety years, the primary record of the genealogy of our branch of the Sandford family has been the book Robert Sandford and His Wife Ann Adams Sandford with Some of Their Descendants, 1615-1930, written by Josephine Sandford Ware. This 85 page account has been floating around our family since its 1930 publication. It can easily be found today on the internet.

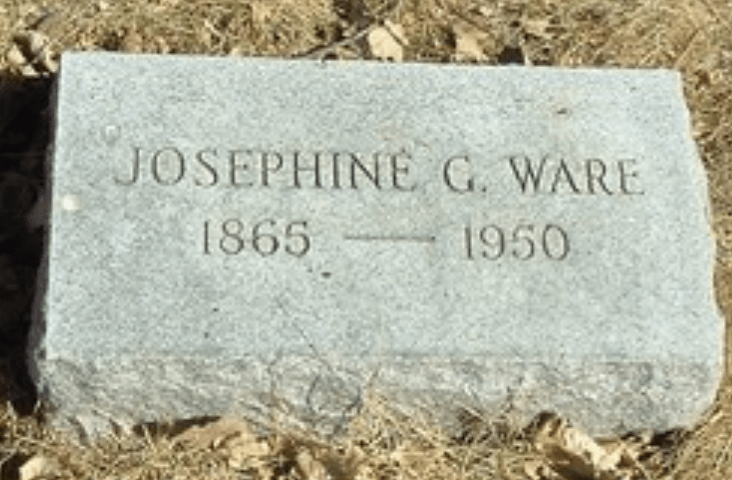

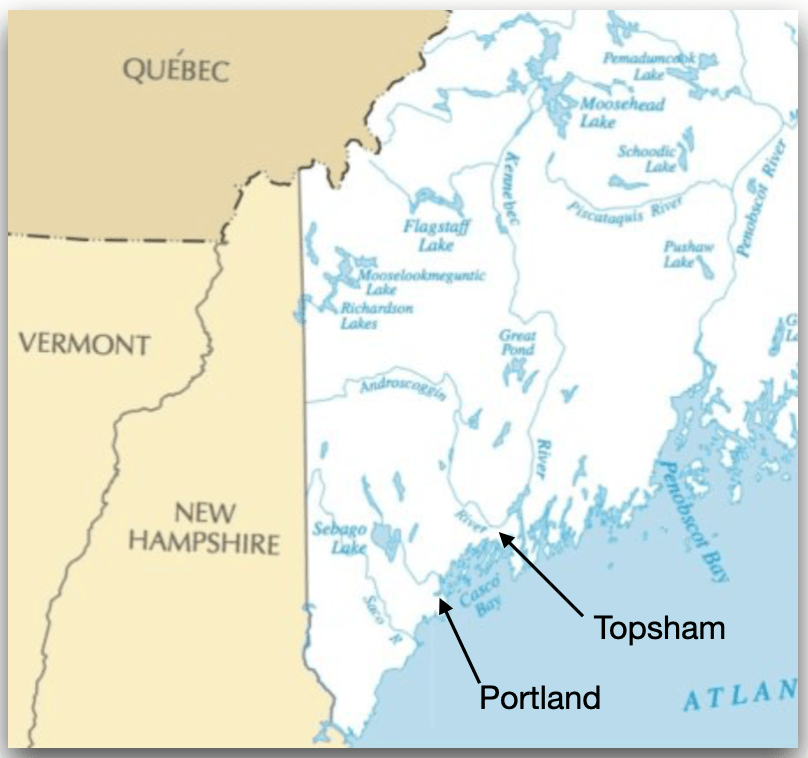

Josephine (1865-1950) was a great granddaughter of John Sandford, the patriarch of the other Sandford branch to have left Bridgehampton, Long Island before the American Revolution to take up residence in Topsham, Maine. Josephine was the same generation as our great grandfather Edward T. Sandford, and is our 4th cousin. At the end of the 1890s she moved with her husband from Maine to Durango, Colorado where they raised at least one son. She died in Los Angeles, but is buried in the Fairmount Cemetery in Denver. It seems likely that our grandfather Joe Sandford knew her (he certainly knew of her) and contributed his and his father’s stories to the book.

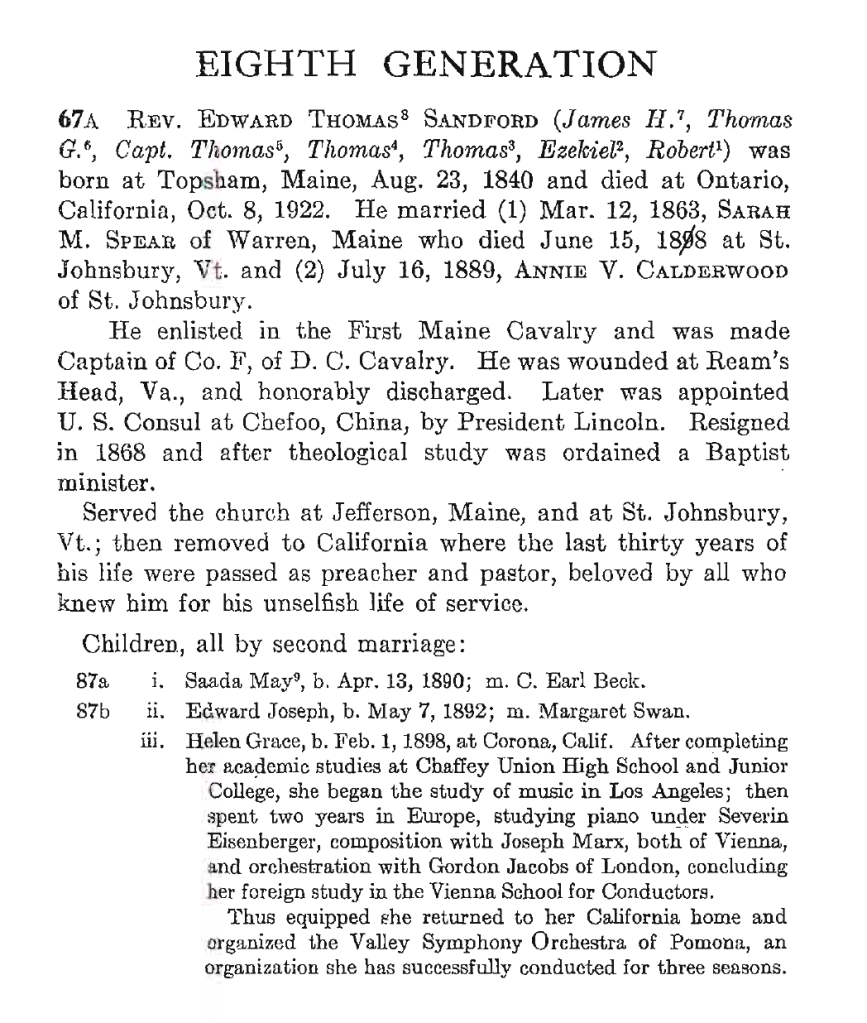

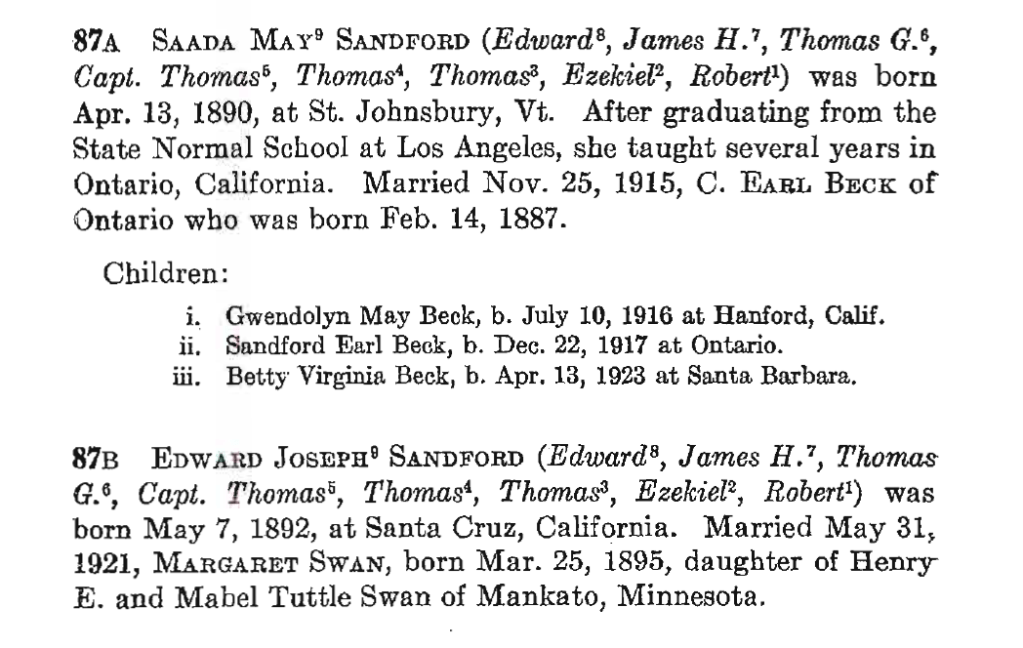

The book follows the standard format established for family genealogies over the past 150 years. It begins with the three Sandford brothers (Robert, Thomas and Andrew) coming to Connecticut with uncle Andrew Warner around 1634, then follows Robert’s line down through the centuries. One branch of the tree ends with grandfather Joe Sandford and names his first three children including our father Gordon Thomas Sandford (with a typo—he was born in 1929 not 1926).

(Note: Sarah Spear died in 1888, not 1898 as shown in the text.)

(Note: Gordon Sandford was born in 1929, not 1926)

In 2019, Janelle and I traveled to Bridgehampton to see the Sag Pond bridge and other sites. There we met seventh cousin Ann Sandford, who has written books on Bridgehampton and her branch of Sandfords, and Julie Greene from the historical society. It was good visit and came with a bonus—our introduction to another Sandford genealogy, The Sandford/Sanford Families of Long Island, Their Ancestors and Descendants written by Grover Merle Sanford of Farmingdale, New York, published in 1975. (Spellings of the name alternate with and without the extra “d” in various branches of the family.) It quickly became evident that this was the preferred source used by the Bridgehampton folks, so I photographed several pages (and have since copied the whole thing from the Library of Congress) with the intent of comparing notes.

The first sign of trouble was in a paragraph on the original Robert Sandford account we read while sitting in Julie’s office:

“Robert’s wife was named Ann, who was not the daughter of Jeremy Adams, as sometimes stated. The only clue to her identity is the statement made by Winthrop in 1667 that Robert Sanford’s wife was a sister of Thomas Skidmore’s wife of Fairfield Conn….“

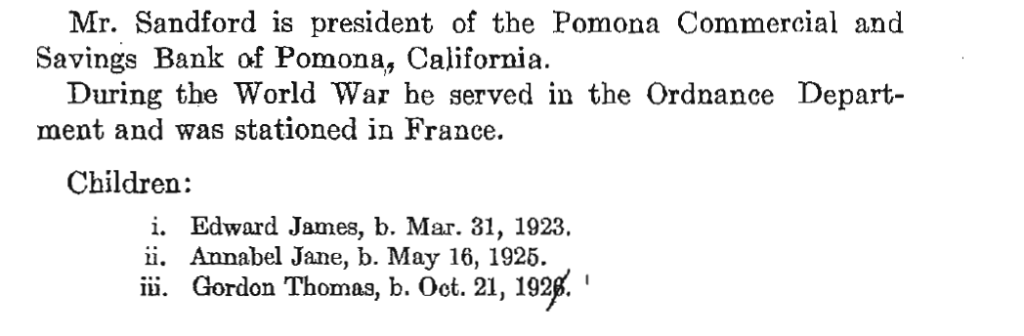

To make a long story short in terms of deciding who to believe on this and other discrepancies, it’s pretty clear that Grover’s (with no disrespect intended I will refer to these genealogies by the authors’ first names, for brevity, since the last names are the same) accounts are better substantiated. His version is written 45 years later than Josephine’s, with full cognizance of her earlier conclusions, and he is very careful about noting his discrepancies with her work, and providing substantiating evidence to back up his conclusions.

With this quickly evaporated the notion that Jeremy Adams, whose name appears on the stone column listing Hartfords original settlers, was 8th great grandmother Ann’s father and therefore our 9th great grandfather. Gone also was the notion that we might be President John Adams’ 4th cousin. But the thing that really bothered me was that this also challenged the story of Zachariah Sandford and his role in the Connecticut Charter Oak incident.

The story hinges on Zachariah having inherited the inn from his grandfather, Jeremy Adams, who is known to have been its previous owner. If Robert’s wife Ann was not the daughter of Jeremy, then Jeremy would not be Zachariah’s grandfather, and how would the inn possibly have come to be owned by Zachariah?

In this case, It only took a few hours of research to find an alternative solution, well supported by evidence, that Zachariah had actually married Sarah Willet, Jeremy’s granddaughter, so the inn had come to Zach via his grandfather-in-law, not his grandfather.

(Grover vs. Ware genealogies).

Uncle Zach’s role in Connecticut history was safe, however, Josephine’s genealogy took a direct hit (including the very title of the book claiming Robert’s marriage to Ann Adams).

Josephine humbly opens her book with the following line:

“That there are errors in the work is probable, but let him who discovers any be thankful there are no more than appear. The editor would be grateful to have corrections and desired changes sent to her that they may be used in a later edition.“

I am thankful for this, but more thankful for the full scope of cousin Josephine’s work (of which there was no later edition).

Alas there is another error in Josephine’s book, this one more significant and difficult to resolve. Upcoming posts will go into this in great detail.

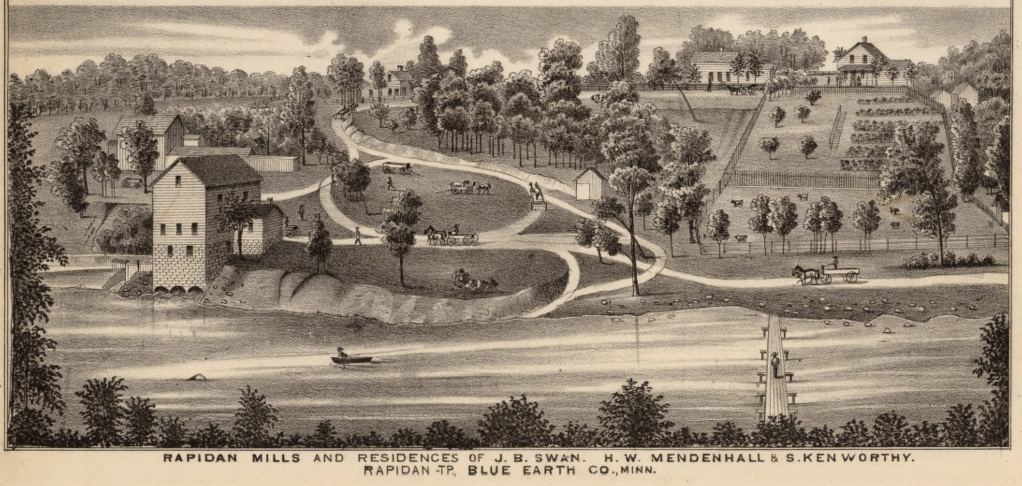

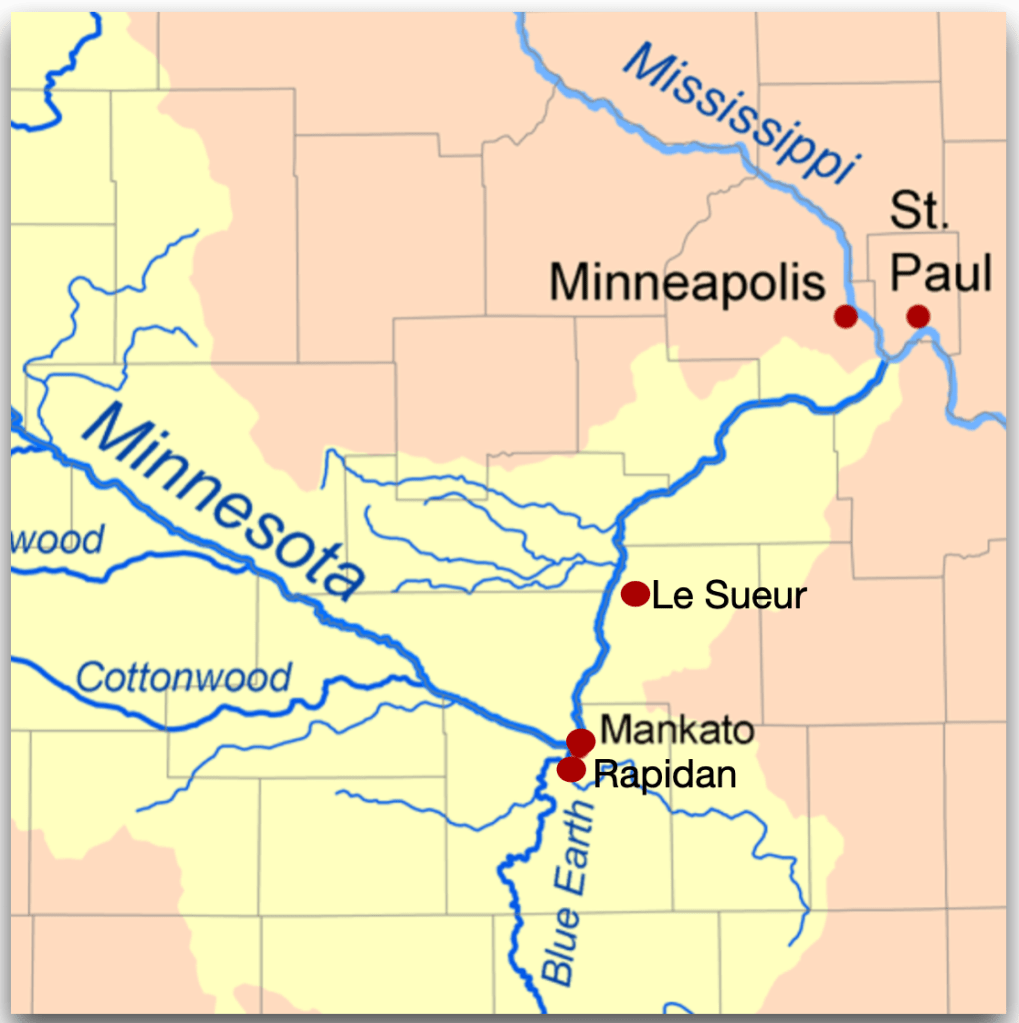

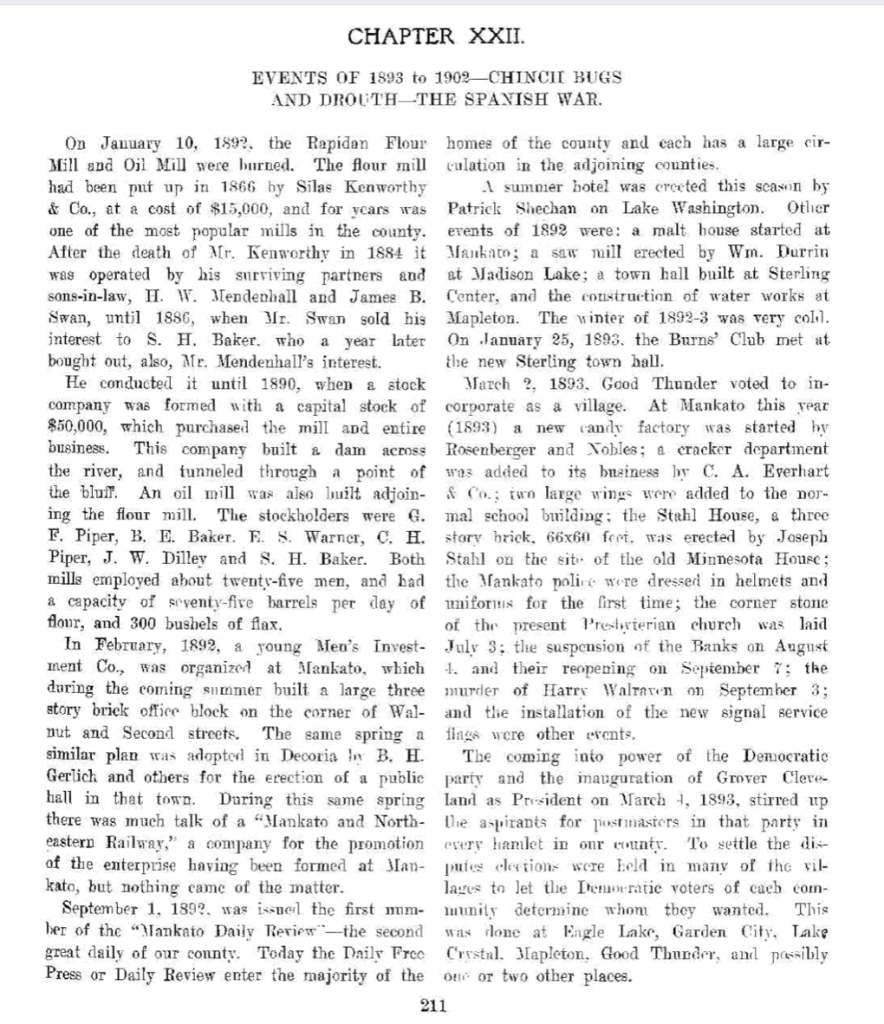

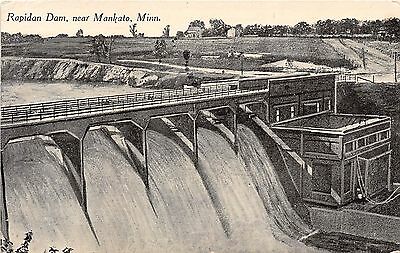

A good anchor point for the story of great grandfather Henry Edson Swan is this lithograph published by Alfred Theodore Andreas in 1874 as part of a larger collection of 19th century maps of the midwest. Grandma Margaret gave a copy of this to Claire years ago.

A good anchor point for the story of great grandfather Henry Edson Swan is this lithograph published by Alfred Theodore Andreas in 1874 as part of a larger collection of 19th century maps of the midwest. Grandma Margaret gave a copy of this to Claire years ago.

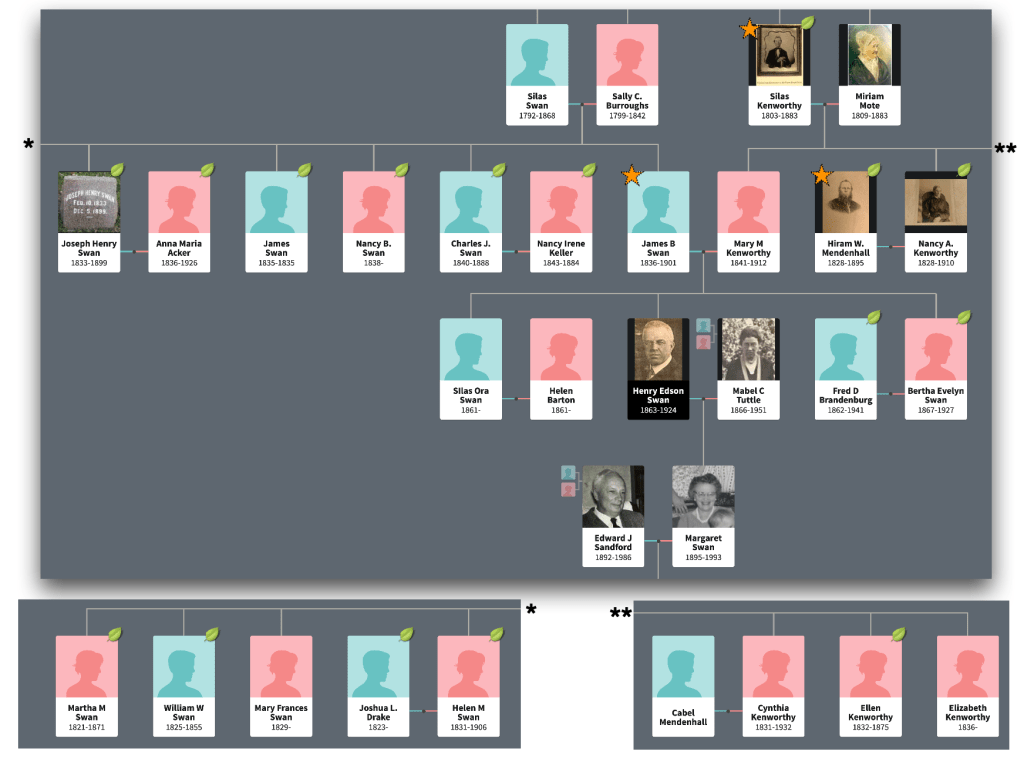

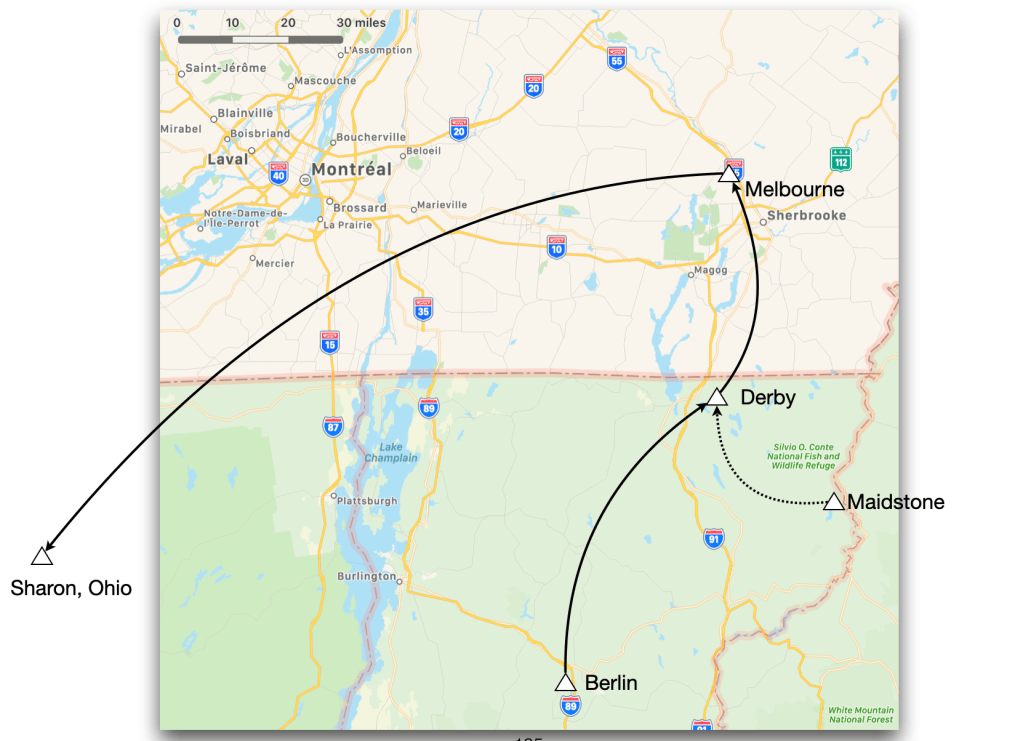

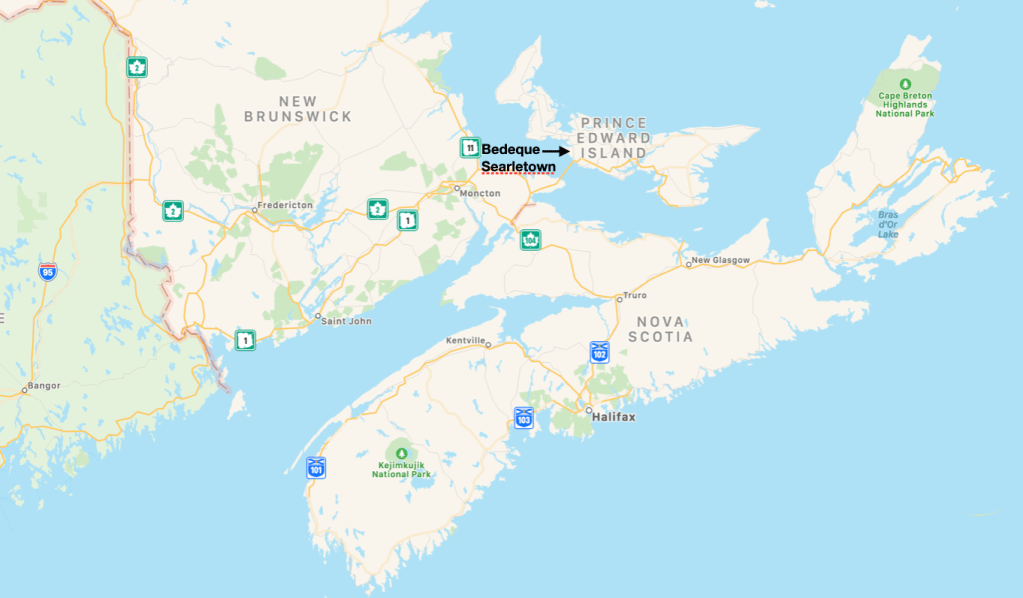

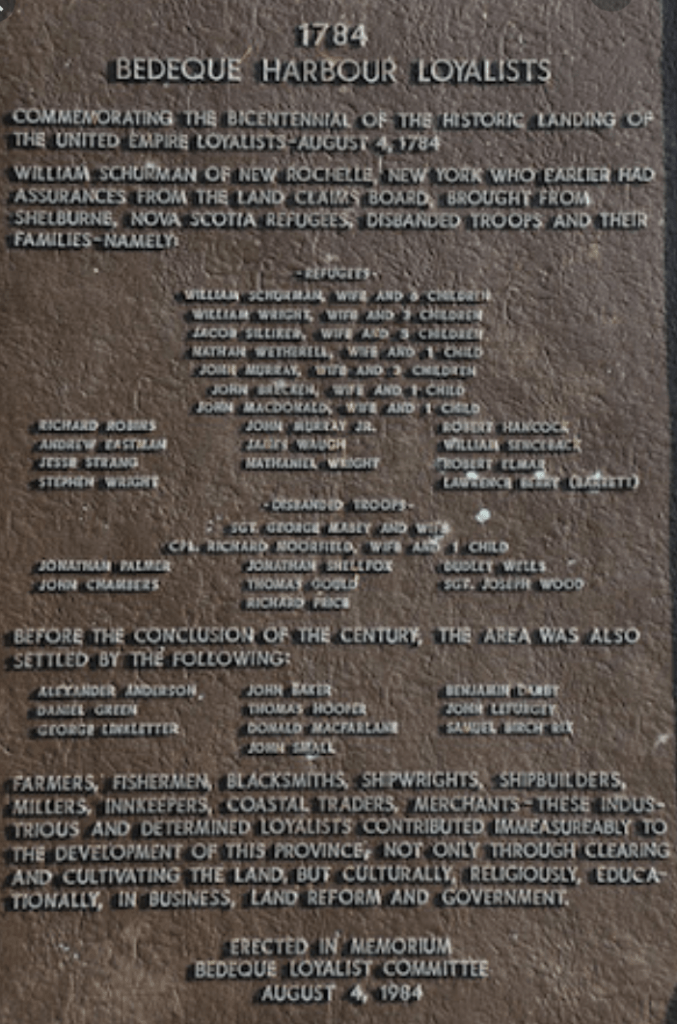

The family of great grandmother Laura Jane Wright immigrated to America twice in 250 years.

The family of great grandmother Laura Jane Wright immigrated to America twice in 250 years.

A final comment on genealogical research as I have come to understand it. Among several things, “Bridging the Silences” refers to filling in gaps between available historical records to understand what probably went on and developing it into a story line that is honest, accurate, and interesting. There are many situations where records simply do not exist to answer a question directly, but logical reasoning, linked with other insights into the life being studied, is useful to determine the likely answer. Short of finding an undiscovered stash of records or letters in an attic somewhere, this is often the best that can be done with the available record. In such cases, I intend always to identify my conclusions as “likely based on reasoning” vs. “proven”, but I also am comfortable embracing these types of well-reasoned conclusions in my overall understanding of the truth regarding our ancestry.

A final comment on genealogical research as I have come to understand it. Among several things, “Bridging the Silences” refers to filling in gaps between available historical records to understand what probably went on and developing it into a story line that is honest, accurate, and interesting. There are many situations where records simply do not exist to answer a question directly, but logical reasoning, linked with other insights into the life being studied, is useful to determine the likely answer. Short of finding an undiscovered stash of records or letters in an attic somewhere, this is often the best that can be done with the available record. In such cases, I intend always to identify my conclusions as “likely based on reasoning” vs. “proven”, but I also am comfortable embracing these types of well-reasoned conclusions in my overall understanding of the truth regarding our ancestry.

Since I have no photos of great grandmother Bessie Gordon, I am using this historic image of downtown Newburgh, New York to represent her branch of the family. In ways that we will explore, Bessie is the most enigmatic of our great grandparents. Her father, James Gordon, came to Newburgh from Northern Ireland in the mid 19th century and became a physician. Her mother, Jeanette (Nettie) Johnston, came from a prominent family of western New Jersey which can be traced back several generations to the early origins of the colony. James and Jeanette had four children of whom Bessie was the oldest. Son Edward followed in his father’s footsteps to become a physician. Daughters Addie and Jennie were the youngest.

Since I have no photos of great grandmother Bessie Gordon, I am using this historic image of downtown Newburgh, New York to represent her branch of the family. In ways that we will explore, Bessie is the most enigmatic of our great grandparents. Her father, James Gordon, came to Newburgh from Northern Ireland in the mid 19th century and became a physician. Her mother, Jeanette (Nettie) Johnston, came from a prominent family of western New Jersey which can be traced back several generations to the early origins of the colony. James and Jeanette had four children of whom Bessie was the oldest. Son Edward followed in his father’s footsteps to become a physician. Daughters Addie and Jennie were the youngest.