![]()

![]()

On the morning of Tuesday, May 20, 1924 our great grandfather Henry Swan presided over a monthly directors meeting of the First National Bank of Ontario, California, where he was the bank president. The routine meeting was adjourned and Henry left for lunch. That afternoon, there was scheduled a monthly board meeting of the Euclid Savings Bank, where Swan was a director. When the normally punctual Swan did not appear for the 3:30 meeting, his associates became concerned for his health, which was known to be poor. A call to the First National revealed that Swan had not returned from lunch. The board members got no answer when they tried telephoning the Swan home–his wife, our great grandmother, Mabel Swan was known to be spending the day in Los Angeles. Oscar Arnold, vice president of the First National Bank and president of the Euclid Savings Bank, and Charles Lattimer, a board member of the Euclid Savings Bank, then went to the Swan home at 501 North Vine Avenue. They found Marshall Sellman, the gardener, working at the home, but he had not seen Swan since early morning. When they found Swan’s car parked in the garage, the three men began searching the home. They found Swan in the upstairs bathroom, having taken his own life. Medical assistance was summoned, but it was quickly determined that he had been dead for several hours.

On the morning of Tuesday, May 20, 1924 our great grandfather Henry Swan presided over a monthly directors meeting of the First National Bank of Ontario, California, where he was the bank president. The routine meeting was adjourned and Henry left for lunch. That afternoon, there was scheduled a monthly board meeting of the Euclid Savings Bank, where Swan was a director. When the normally punctual Swan did not appear for the 3:30 meeting, his associates became concerned for his health, which was known to be poor. A call to the First National revealed that Swan had not returned from lunch. The board members got no answer when they tried telephoning the Swan home–his wife, our great grandmother, Mabel Swan was known to be spending the day in Los Angeles. Oscar Arnold, vice president of the First National Bank and president of the Euclid Savings Bank, and Charles Lattimer, a board member of the Euclid Savings Bank, then went to the Swan home at 501 North Vine Avenue. They found Marshall Sellman, the gardener, working at the home, but he had not seen Swan since early morning. When they found Swan’s car parked in the garage, the three men began searching the home. They found Swan in the upstairs bathroom, having taken his own life. Medical assistance was summoned, but it was quickly determined that he had been dead for several hours.

Family friends Earl and Mary Richardson were quickly informed of the situation. They waited at the Pacific Electric trolley station, intercepting Mabel as she returned from Los Angeles. Word was sent to Joe and Margaret, who had recently moved to Pomona. They rushed to Ontario with 14 month-old son Ned. The facts of the situation are so extreme–the sudden death, the news of suicide, the shocking facts of how it took place, and the absence of any note or explanation–that it is hard to fathom how one would go about breaking such news to family members, any withholding of detail providing only temporary respite from realities that would surely come to light in another day or two. The Richardsons would care for the family assiduously over the next few days.

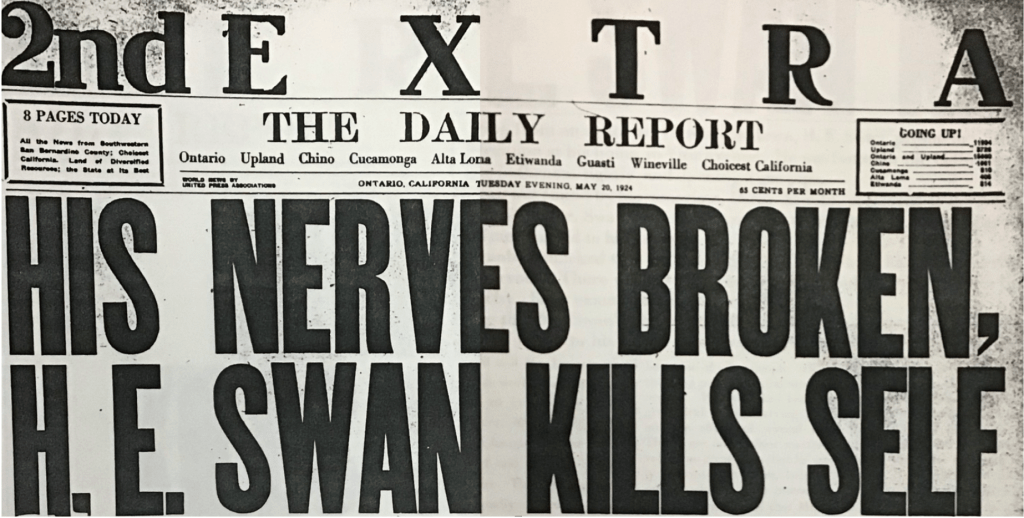

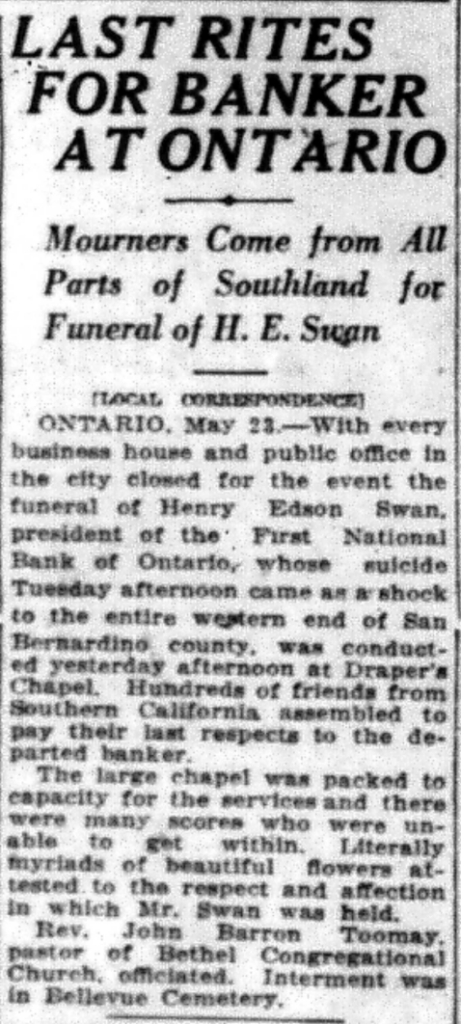

News of the tragedy spread quickly through the Southern California region. The Ontario Daily Report published at least three extra editions devoted to the news of one of city’s most beloved leaders.

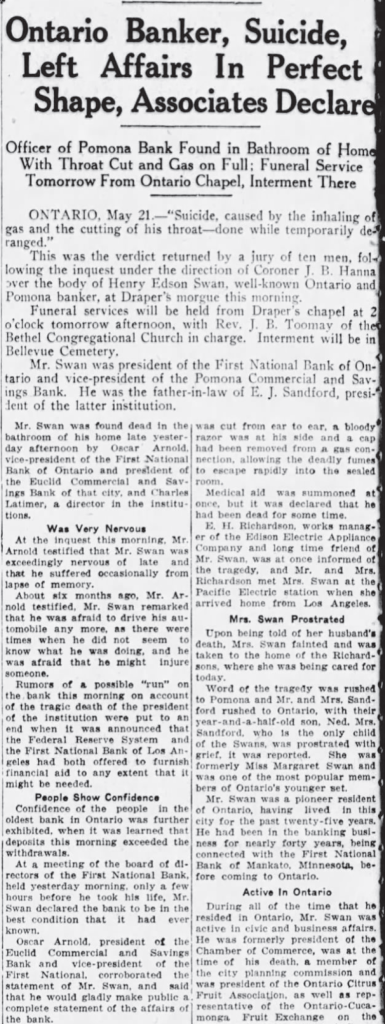

The suicide of a prominent banker inevitably raises questions of possible financial improprieties and such speculations arose within hours of the news breaking. Banking officials, including Oscar Arnold quickly released statements of the known facts, that the bank had passed state audits with flying colors a week earlier and that the monthly board meeting earlier in the day had been completely routine. Subsequent investigations found absolutely nothing out of order with the finances of the bank, nor with any of Swan’s personal finances.

The coroner’s official assessment of Swan’s death was “suicide caused by inhaling of gas and cutting his throat while temporarily mentally deranged.” A century of reflection and speculation on the circumstances of Henry’s death has revealed little more explanation than what was printed in the newspapers in the days immediately following. Here is a summary.

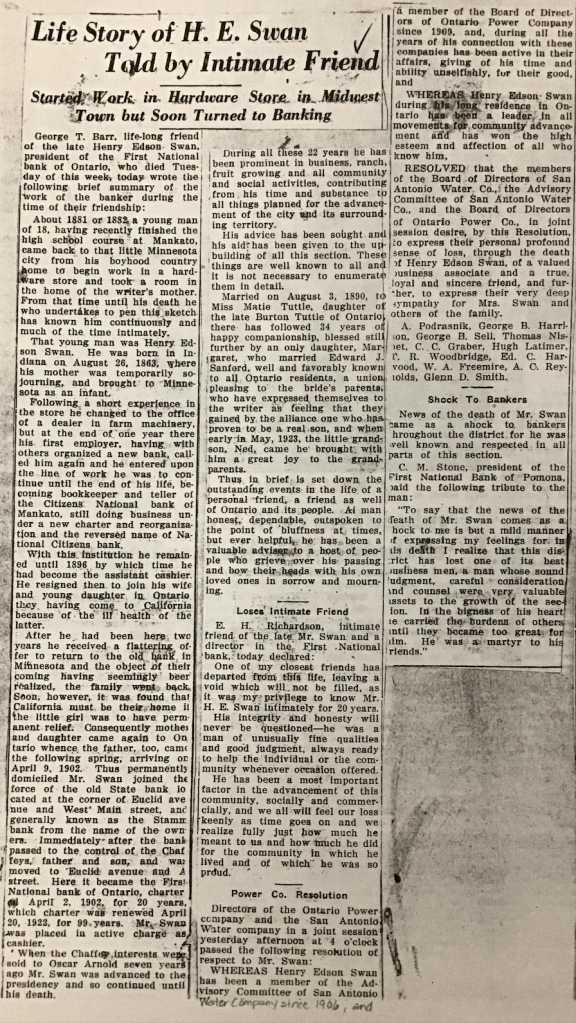

Henry’s bad health had been known in the family for about the previous three years. Henry himself was acutely aware of his health problems and was quoted, for example, as saying that he increasingly did not trust himself to drive. As his friend and colleague Oscar Arnold explained…

Mr. Swan has been suffering physically for some time. Three years ago he began to show signs of a nervous breakdown, not apparent to his friends, but to his family. He had high blood pressure and his immediate family feared that something might happen to him in the next few years, as he was just about 60 years old, and several of his family had broken down about that age.

Several weeks ago Mr. Swan said to me that he thought he must take a vacation of several months or he would break down, he felt like a nervous wreck. I told him to go at once, but he said he would wait a little while and then would like to go away for the summer to recover completely.

Oscar Arnold, Ontario Daily Report, May 20 1924.

Everyone must have deeply regretted that this anticipated summer retreat was only a few weeks away when Henry died.

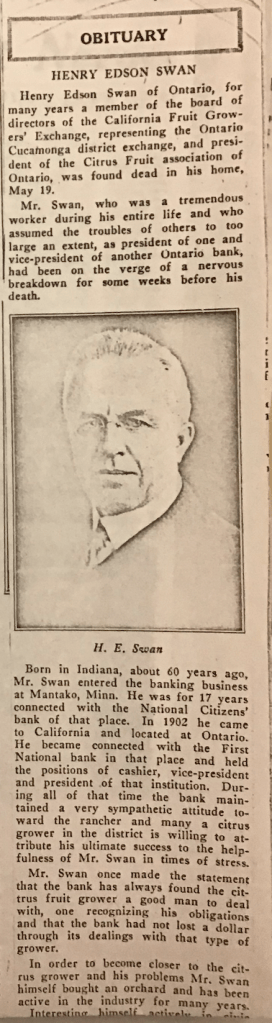

Several of Henry’s relatives did indeed die during their early-mid sixties. He would have known that his older brother, Silas Swan, had died just a few months earlier in Minnesota at age 63. His father James Burroughs Swan had died at age 64. (Younger sister Bertha Swan would die at age 60 a few years later.) The specific causes and circumstances of these deaths are not known, but Henry’s odds were certainly not good, and he knew it.

Almost all remembrances of Henry noted that he worked too hard and took many of his clients’ problems (particularly the orange growers’ finances) too personally, adding to the stress of his job.

As to Henry’s state of mind on the day he took his own life, it was clearly irrational, well beyond that of a man deeply troubled by overwork and poor health, well-deserving of the label “temporarily mentally deranged”. His final actions were decisive and redundant, leaving no possibility that he would be discovered and revived. Beyond the suicide itself and the extreme nature of his methods, two things point to his state of total irrationality. First, his full opening of the gas jets in the room created a high danger of destroying the house and killing other people. Second, he gave no thought to who would find his body. Had the bank directors been a little less persistent in their search for Swan, it is most likely that Mabel would have been the one to find his body. No matter how desperate, had Swan retained any capacity for rational thought that afternoon, he would have rejected any actions leading to these possible outcomes. Henry simply was not Henry in his final hours.

I believe that in his final years Henry was not able to see a world in which he backed away from his commitments and lived quietly to prolong his life. If there was any window of time when this would have been possible, it would have started closer to the beginning of his three year health decline than the end. He just was not wired this way.

We can also look back on Henry’s actions in the year before his death and wonder how much was him deliberately getting his affairs in order. His entering into the partnership with Joe to purchase controlling interest in the Pomona bank surely had a strong element of wanting to set up his daughter, son-in-law, and grandson for the future. It surely must have occurred to him that the month spent with Mabel in the Hawaiian Islands the previous summer could have been his last opportunity to travel in the way he loved.

Remembrances of Henry filled the newspapers and preoccupied the town in the days that followed. A consistent theme was giving him a level of credit for the development and success of the regional orange growing industry equal to that of the orange growers themselves.

Henry was buried at Ontario’s Bellvue Cemetery Funeral that Friday. Ontario businesses were closed that day, and overflow crowds attended the funeral.

The shock waves from Henry’s death dissipated over time but never completely faded. The subject was rarely discussed in the family. Joe, in his living history interviews decades later, would occasionally bring up Henry in making some general point on how things used to be. Sitting next to his wife, he would speak fondly of his father-in-law, but then quickly move on to another topic. Interviewers did not ask about Henry, probably understanding this topic to be off limits.

Margaret, who was 29 at the time of her father’s death, was never quite the same. Certainly her high-society-girl status had already begun to fade in the realities of family life, but she lost much of her enthusiasm for this type of life, settling down to raise her family and eventually become the grandmother we knew. And there must have come a day when she realized that her son Richard (and later several of his sons) bore a striking resemblance to her late father.

Joe, at age 32 lost a partner and a role model, perhaps responsible for nearly as much of his life-view as his own father who had died two years earlier. He stepped full-on into his banking career in the years to follow, guided by the icon of his deceased mentor. Henry’s death led to specific challenges in the Pomona bank, including a (constructive) takeover in the following months, which Joe, as bank president, would manage with the steady hand and confidence he had learned in large part from his father-in-law.

In the aftermath of Henry’s death, family plans were modified. Joe and Margaret sold their new home in Pomona and moved back into the Ontario home at 501 North Vine, eventually assuming ownership, and living there for most of the rest of their lives. Mabel remained there with them for the rest of her life. The reasoning behind the decision to live in the home haunted by Henry’s death is not known, but perhaps the obvious discomfort was weighed against the opportunity to preserve the home and orchard which Henry had loved. Joe and Margaret had not lived in Pomona for long and it may also be that they were a little homesick for Ontario, deciding to take the opportunity to reverse their decision to move. The five mile commute from Ontario to Pomona for Joe would never have been a big factor.

Mabel eventually got back on her feet with continued charity work, watching her grandchildren grow up, and doing some traveling in her later years.

Henry’s tools would remain locked in the shed next to the garage for the next half century, mostly undisturbed and unused. It was a curiosity for us to peer into the shed during our visits as children.

Perhaps the biggest sign of the family’s recovery came nearly a year after Henry’s death, when Margaret gave birth to the family’s second child, our future aunt Anabel.

4 thoughts on “Death of an Icon”