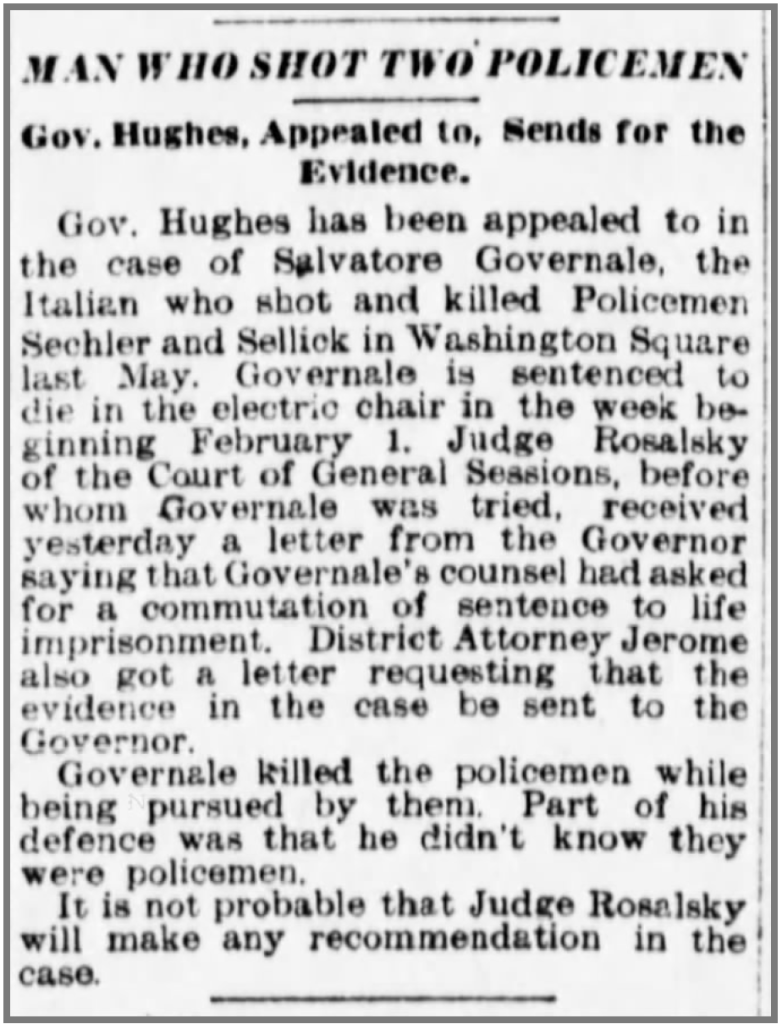

![]() In the aftermath of the murders of our great grandfather George Sechler and Alfred Selleck, the trial of Salvatore Governale proceeded at lightning speed by today’s standards. The indictment was dated Monday, April 29, 1907, two weeks and one day after the murders. The trial in a Manhattan courtroom began a week later on Tuesday, June 4 and concluded late in the day on Tuesday, June 11.

In the aftermath of the murders of our great grandfather George Sechler and Alfred Selleck, the trial of Salvatore Governale proceeded at lightning speed by today’s standards. The indictment was dated Monday, April 29, 1907, two weeks and one day after the murders. The trial in a Manhattan courtroom began a week later on Tuesday, June 4 and concluded late in the day on Tuesday, June 11.

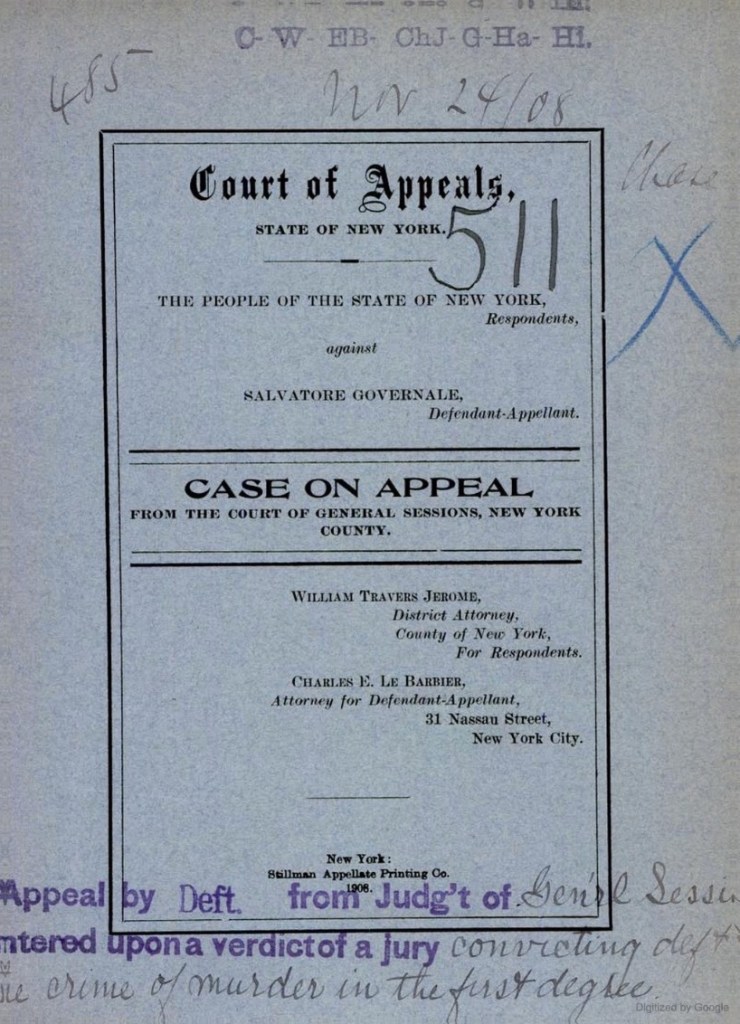

Records of the appeal of Governale’s first degree murder conviction remain available today in an e-document that can be found with a simple internet search. The majority of the document is the complete transcript of the original trial.

In this jury trial, New York Assistant District Attorney Arthur C. Train, Esq. argued for the people (prosecution) and Thomas C. Whitlock, Esq. for the defense. The judge was the Hon. Otto A. Rosalsky. The trial was specifically for the murder of George Sechler–presumably to allow for another trial for the murder of Alfred Selleck if the first case had been unsuccessful for some reason. George’s case was probably selected to go first because he had a wife and young baby, therefore it was the case that elicited the most public sympathy and outrage.

The trial transcript provides insights and information about the specific events of April 14, 1907 which were not available or clear in the press, or which the press got wrong. I will repeat the story of that day, with corrections included.

Sunday April 14, 1907 was a beautiful early spring day in Washington Square Park in lower Manhattan, the park with the iconic grand arch. Hundreds of families were enjoying the last hours of their weekend. Around 5:45 (45 minutes before sunset), an altercation arose between 25 year old Salvatore Governale and 19 year old Charles Vincenzo, each man accompanied by his brother. What began as a minor jostle in a public restroom quickly spiraled to a major altercation. Outside the restroom, Governale pulled a gun and began firing. Two shots went into the air, but a third shot hit Vincenzo in the leg. (Although some early reports indicated that Vincenzo was killed, he survived although he was crippled by the injury. He would testify at the trial as a witness for the prosecution.)

New York Police Detective Sergeant John Fogarty was a key participant in the events of April 14 and during the trial. When the first shots were fired in the park, he was just north of the park on 5th Avenue, and came running. He, with others in the crowd, chased Governale south onto Thompson Street, keeping Governale in sight until he turned into the tenement apartment building entrance at 230. His continuous account of the path taken by Governale was important to the prosecution’s case. Governale’s brother fled north and was not involved in the ensuing events.

Officers George Sechler and Alfred Selleck were on West 3rd Street, a block south of the park, when the shots were fired. Both men were working in plainclothes. They were near each other at the time, but not working together. As Governale fled south on Thompson Street followed by his pursuers, Sechler and Selleck ran east, encountering Governale at the intersection of W. 3rd and Thompson. Both men tried to stop Governale, Selleck first, then Sechler. Both were knocked down, got up, and resumed the chase southward. A half block later, Governale turned into the building entrance at 230 Thompson Street. The hallway was dark. Beyond a stairwell there was an inner door leading to a courtyard which may have been locked. Governale crouched next to the stairwell as Selleck entered the building followed immediately by Sechler.

Governale’s gun held five rounds, three of which had already been fired in Washington Square Park. Governale shot Selleck in the upper chest just as Sechler rushed in behind him. George is credited with shielding Selleck from another shot, which resulted in he himself being hit by the fifth and final bullet

Accounts differ at this point–either Governale ran out of the building and was immediately apprehended by a citizen and Sergeant Fogarty as he arrived on the scene and as Sechler emerged from the building, or, Fogarty entered the building and apprehended Governale with Sechler’s assistance, the two bringing Governale out to the street. Either way, Fogarty was fortunate that Governale had already fired his last shot, lest he become a third victim. On the street Sechler told Fogarty that Selleck had been shot, then quickly realized that he too had been shot.

Fogarty maintained control over Governale, pulling him back up Thompson Street with Sechler right behind, to a drug store where they found other officers who were able to assist.

A key revelation of the trial transcript is that both Sechler and Selleck were armed but probably never had time to draw their weapons in the fast moving events. The time between their hearing the shots from the park and the shootings in the hallway must have been about two minutes.

In the drug store Sechler turned his weapon over to another officer and also gave him his gold watch on a chain for safekeeping (the whereabouts of the watch is unknown today). A wagon was commandeered to take Sechler to Saint Vincent’s Hospital, about 8 blocks away. Selleck was initially taken to a different drug store by other officers. He was conscious for a time following the shooting.

At the hospital, both officers were in the same room. George remained conscious. The bullet had clipped his lung, he was hemorrhaging, and he soon understood that his wound was likely mortal. Steps were taken to obtain dying declaration testimony from him that would be admissible in court. For this, it was important that George declare his awareness of his grave situation as the foundation for testimony that would not be possible to cross-examine. An excerpt from the court transcript shows how this played out in testimony from Sergeant Fogarty describing Sechler’s exchange with Officer/Roundsman Delay, who was interviewing Sechler.

Sechler’s dying declaration was eventually admitted into evidence. George’s statement “I want you to send for my wife and baby, so I can see them”, although stricken from the record, was heard by the jury.

A second form of dying declaration was also taken from Sechler. The transcript reveals that Governale was actually taken to the hospital room for Sechler to identify. This identification was not allowed into the trial evidence because of legal technicalities, but it hardly mattered as there was no doubt as to Governale’s identity as the man who shot George Sechler.

Our great grandmother Laura Sechler was indeed summoned from her Brooklyn home. She, holding her baby (our grandmother Ruth), was taken over the Brooklyn Bridge and transferred to a waiting Police Commissioner’s car and brought to the hospital. Accounts differ as to whether George succeeded in seeing his family. Several papers published an account of the baby being placed in Georgeʼs arms before he was taken to surgery. Other accounts state that this was a story made up by overzealous reporters and that George was taken to surgery before he could see his family. George died at 10:30pm in surgery. Alfred Selleck died two days later.

Thee trial itself is a fascinating study in legal procedures, some of which might be indistinguishable from current day proceedings, others not.

Several times during the proceedings, members of the jury interrupted directly with questions to the attorneys, court, or witnesses, something that is hard to imagine by today’s rules.

The two adversaries, Train and Whitlock, proceed with their cases in a professional and civil manner. They were playing a week long chess game, less for the jury (whose conclusion seems to have been a pre-ordained conclusion) and more for the benefit of a future Court of Appeals. Whitlock records objections to nearly every aspect of Train’s case. Although 95% of these objections were overruled, they allowed the defense to rack up a long list of possible grounds for a future appeal. He raises so many objections that the court quickly agrees to a shorthand whereby the court stenographer can record the same set of objections each time, without wasting the time of the court.

Aside from leaving every possible door open for a future appeal, the defense’s primary strategy was that of claiming self defense. Both officers were in plain clothes on April 14. It is not clear that either had the opportunity to identify themselves as such before the final confrontation in the hallway, so as to distinguish themselves from the mob that pursued Governale from the park.

Late in the trial Governale took the stand to testify in his own defense. It was the contention of the defense that Sechler and perhaps Selleck fired a shot in the hallway before Governale returned fire. In order to make this case, they had to impugn the testimony of Officer Robert Manley, the officer at the 16th precinct who made the record of the status of the two officers’ guns and who first questioned Governale on the record following the shootings. The official record showed that neither Sechler’s pistol nor Selleck’s had been fired. This led to an exchange where Governale, under cross examination, refuted multiple parts of the record taken after the shootings. There were so many discrepancies between Governale’s earlier deposition and his testimony in the trial that it must have greatly damaged any credibility he might have had with the jury.

Language was a recurring issue during the trial. Although Governale had been in America for more than four years, he did not speak English well, and likely exaggerated his lack of English speaking ability during the trial. The court was careful to follow official procedures for translation, and most of Governale’s testimony was through a translator both on April 14 and during the trial. Language problems were raised as a possible reason for the discrepancies in Governale’s testimony, but this never got much traction with the court or in the later appeal.

Tuesday, June 11 was devoted to, closing arguments, instructions to the jury, and jury deliberations. The jury had the option to convict Governale of several levels of murder, only the most serious of which, Murder in the First Degree, carried the death penalty. That the events of April 14 had unfolded within a 5 minute period did not deter the prosecution from pressing for the highest charge, requiring proof of premeditation. There were legal precedents, brought forth by the prosecution and not disputed in the court, for premeditation in similar cases with short time frames under certain conditions. The circumstances in the park, during the pursuit, and Governale’s specific actions in the hallway all contributed to making the charge of premeditated murder stick. Most damaging in this regard was when Governale, during his testimony under cross examination, admitted that he had shot to kill the officers in the hallway.

On the afternoon of June 11, Attorney Train delivered his impassioned closing remarks, his speech continuing for 24 pages of the trial transcript. It was the honest and straightforward testimony of Sergeant Fogarty which provided the basis for Train’s arguments and his dismantling of Governale’s claims of self-defense.

Jury deliberations lasted less than two hours. The verdict of guilt of murder in the first degree was delivered that same evening. Sentencing was deferred to June 21, 1907, at which time Governale was sentenced to death. An initial execution date of August 5, 1907, was set.

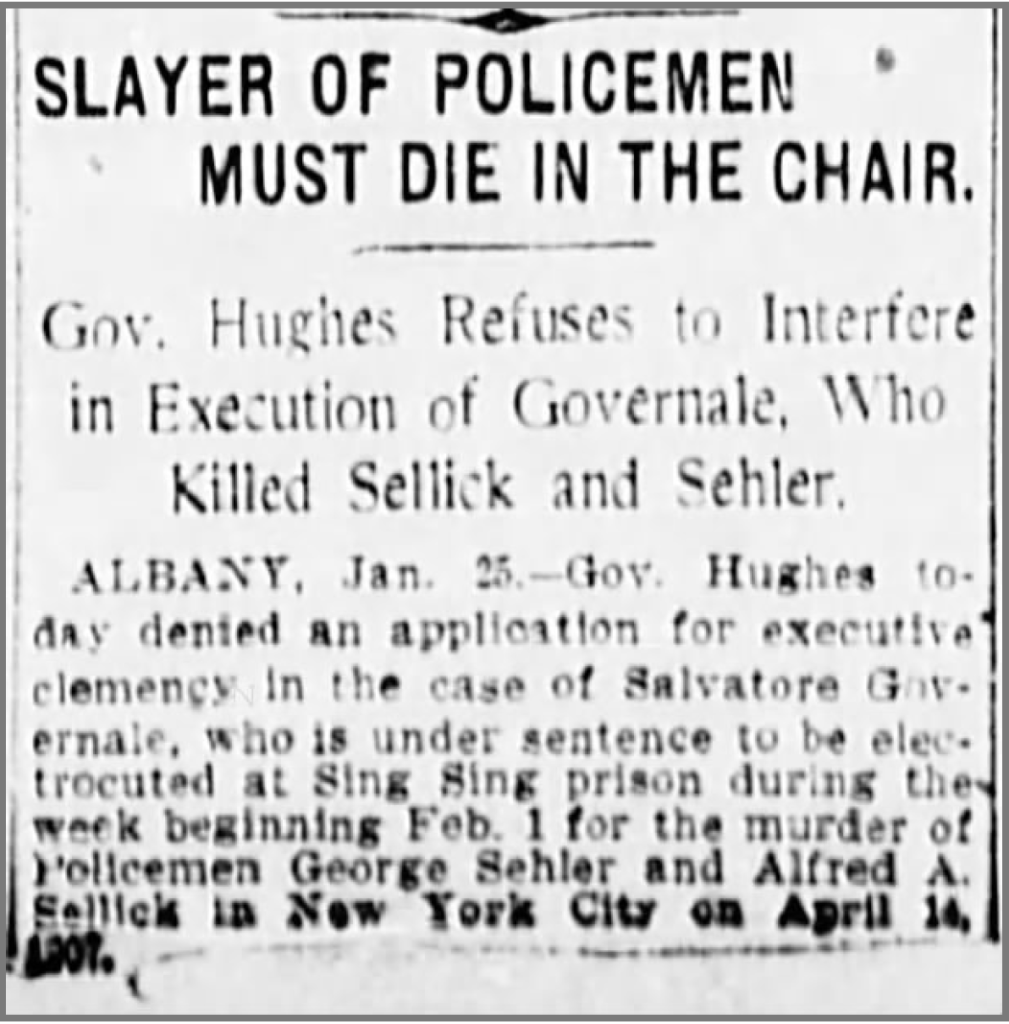

An appeal was filed in July 1907 on behalf of Governale. The appeal and prosecution rebuttal are included in the the trial document. The appeal puts forth ten arguments for reversal of the verdict, the most salient of which center on claims of self defense and improper inclusion of evidence of crimes committed in the park as evidence in the murder trial.

Normally it is improper to present testimony of previous crimes committed by a defendant in a trial, as these would prejudice the jury’s consideration of the current charges. By this reasoning, it could be, and was, argued that the fight and shooting a few minutes earlier in the park were not admissible evidence. In this case, however, events unfolded very quickly, one event leading to the next. Refuting the defense claim of self defense in the hallway relied directly on understanding the nature of the circumstances of the chase down Thompson Street, which in turn relied directly on the nature of the fight and shooting that took place in the park. The December 18, 1908 decision of the Court of Appeals is provided below, in which the judge considers the balance between these issues.

The defendant was indicted for the crime of murder in the first degree. On the trial he was sworn as a witness in his own behalf, and testified that he shot George M. Sechler while in the hallway hereinafter mentioned. He further testified, “I fired to kill.”

On Sunday afternoon, April 14, 1907, about 5:45 o’clock, two young Italian men entered a small building maintained as a urinal near the south end of Washington Square park, in the city of New York. The defendant and his brother were then in the building, but the defendant’s brother had started to leave the building as the young men entered, and one of the young men accidentally “bumped against him,” whereupon a quarrel ensued and defendant’s brother backed the young man against an iron railing. The defendant passed out of the building and ten or twenty feet from the entrance thereof and stood on a grass plot near some shrubbery. The companion of the young man who had been pushed against the railing went to his assistance and after some fighting all came out of the building; the two young men mentioned were leading, and the defendant’s brother was a short distance behind them. As the young men turned in the direction where the defendant was standing he immediately fired a revolver three times in the direction of the young men, one shot from which entered the left leg of the young man that had been to the aid of his companion. As the young man who was shot staggered back the defendant’s brother ran up Fifth avenue and the defendant placed his revolver in his pocket and ran across the lawn to and across Fourth street and down Thompson street. One Fogarty, a lieutenant of the New York police force, then in plain clothes, was about one hundred yards north of where the firing took place. He heard the shots and turned in the direction of the noise and saw the defendant turn and run and he followed him. Several persons in the park followed and the crowd increased as they went south. Fogarty called out, “Stop that man.” About fifty feet north of Third street, Sellick, a patrolman on duty in plain clothes, attempted to stop the defendant. Defendant was then running in the middle of the street and to avoid Sellick he ran upon the sidewalk and jumped over an open cellar way and passed Sellick. Sellick turned and followed him. At about Third street Sechler, a patrolman on duty in plain clothes, attempted to stop the defendant and failed to do so. Sechler immediately turned and followed the defendant. The crowd increased in numbers and at 232 Thompson street the defendant ran into a hallway. Sellick and Sechler followed him. The hall extends back about twenty-one feet from the street entrance and then turns to the left at a right angle to a stairway commencing six feet from the angle. There is a passageway along the right hand side of the stairway leading to a door which opens into a yard or court. The defendant stopped by the stairway. The hallway was quite dark except that the defendant looking from the interior thereof toward the open doorway could see his pursuers at the street. When Sellick and Sechler approached within seven or eight paces of the defendant he shot them both, the shots being fired in rapid succession. Sellick fell, but Sechler ran to and grabbed the defendant not appreciating that he had been mortally wounded. Fogarty followed and Sechler and Fogarty took the defendant to the doorway when Sechler exclaimed, “God, I’m shot.” Help was obtained for Sechler, and he was taken to a hospital, where he died about ten-thirty that evening.

Number 232 Thompson street is about five hundred and fifty feet from where the shooting took place in the park. The defendant in his testimony says that his brother’s assailants during the quarrel fired two shots and that “Because they were beating my brother I fired two shots and then I ran.” He further said that the shots fired by him in the park were fired at the ground to scare his brother’s assailants and not at any particular person and that he ran away to save himself. The young men in the park each testified that he did not have a revolver. The defendant did not produce his brother as a witness nor explain his absence.

In explanation of the shots fired in the hallway defendant says that he supposed the people that followed him were friends of the young men in the park that had the altercation with his brother, and that both of the men who entered the hallway had revolvers in their hands, and one of them fired at him and that he fired to kill because they fired at him. No one heard more than two shots in the hallway, and after the shooting the revolver taken from Sellick, which was a five-shooter, contained four unexploded shells and one empty chamber. It did not contain an exploded shell. The revolver taken from the deceased was a five-shooter and contained five unexploded shells. The jury could have found that the defendant testified falsely in saying that either Sellick or Sechler fired at him. The defendant’s revolver was a five-shooter and contained five exploded shells. So far as the testimony taken on the trial is in conflict with that given by the People it was such that the jury could have believed and they probably did believe the People’s testimony as against that given by the defendant and the witnesses produced on his behalf.

The testimony offered on behalf of the People supplemented by the admissions of the plaintiff prove beyond controversy that the defendant shot and killed Sechler, and that he intended to kill him. It was necessary for the jury to determine two important and seriously controverted questions, viz.: 1. Did the defendant shoot Sechler with a deliberate and premeditated design to effect his death? 2. Did the defendant shoot Sechler in the lawful defense of himself? The jury determined these questions against the defendant.

The defendant’s principal contention on this appeal is that the trial court erred in allowing testimony of what occurred in the park to be received and considered by the jury in determining whether the defendant was guilty of the crime of murder in the first degree.

It is a general rule that evidence of a crime which is distinct and independent of the one of which the defendant stands indicted cannot be received on his trial. The commission of one crime is not in itself any evidence to be considered by a jury in determining a defendant’s guilt of another crime in no way connected therewith. A person cannot be convicted of one offense upon proof that he committed another, however persuasive in a moral point of view such evidence may be. It would be easier to believe a person guilty of one crime if it was known that he had committed another of a similar character, or, indeed, of any character; but the injustice of such a rule in courts of justice is apparent. It would lead to convictions, upon the particular charge made, by proof of other acts in no way connected with it, and to uniting evidence of several offenses to produce conviction for a single one. ( Coleman v. People,55 N.Y. 81; People v. Molineux, 168 N.Y. 264.)

Evidence of the occurrences in the park was not proper to be considered by the jury in determining whether the defendant shot Sechler, neither was it proper for their consideration for the purpose of determining that the shooting of Sechler was done by the defendant while engaged in the commission of a felony in the park. The shooting in the park was an independent crime. ( People v. Huter, 184 N.Y. 237.) There are exceptions to the general rule excluding all evidence of crimes alleged to have been committed by a defendant other than the one for which he is being tried. ( People v. Molineux, supra.) The important questions for the jury in this case were the two that we have hereinbefore enumerated. The occurrences disclosed in the record beginning at a time when the shots were fired in the park and ending with the defendant’s arrest include but a very few minutes of time, and they all have a distinct relation to and bearing upon the defendant’s apprehension of great personal injury by his pursuers and upon his intent in shooting Sechler. A private person as well as a peace officer may without a warrant arrest a person for a crime committed in his presence, and when the person arrested has committed a felony, although not in his presence. (Code Criminal Procedure, sec. 183.)

If the defendant committed a felony in the park any of the persons present or those that followed him had express statutory authority to arrest him. Even the statutory requirement that before making an arrest a private person must inform the person to be arrested of the cause thereof and require him to submit, does not apply to a case where the person arrested is in the actual commission of the crime or is arrested on pursuit immediately after its commission. (Code Criminal Procedure, sec. 184) The intent and purpose of the defendant’s pursuers and their rights in regard to interfering with the defendant were very material. If the defendant was wholly innocent of any crime and not liable to arrest and he was pursued by a mob intent upon taking his life or of doing him great personal injury his rights in self-defense would have been entirely different from what they were as a criminal fleeing from justice. It was material, therefore, to show the occasion for the defendant’s fleeing from the park and the purpose of his pursuers or some of them in following him into the hallway.

The defendant’s right to defend himself is stated in section 205 of the Penal Code which says: “Homicide is also justifiable when committed, either 1. In the lawful defense of the slayer, * * * when there is reasonable ground to apprehend a design on the part of the person slain * * * to do some great personal injury to the slayer * * * and there is imminent danger of such design being accomplished; * * *.”

Any person committing violence in his personal defense must not only believe that he is in danger of personal violence but he must in fact have reasonable ground to apprehend that he is in imminent danger.

When one who is without fault himself is attacked by another in such a manner or under such circumstances as to furnish reasonable ground for apprehending a design to take away his life or do him some great bodily harm and there is reasonable ground for believing the danger imminent that such design will be accomplished, he may safely act upon appearances and kill the assailant if that be necessary to avoid the apprehended danger and the killing will be justifiable although it may afterwards turn out that the appearances were false and there was in fact neither design to do him serious injury nor danger that it would be done. ( Shorterv. People, 2 N.Y. 193; People v. Taylor, 177 N.Y. 237.)

The jury could have found that the defendant committed a crime amounting to a felony in the park. The defendant was, therefore, not without fault on his part. Had he any reasonable ground under the circumstances disclosed to apprehend that Sechler designed to do some great personal injury to him, and that there was imminent danger of such design being accomplished? If the defendant had committed a crime in the park amounting to a felony, he knew that he was subject to arrest. The jury could have found that the defendant stated subsequent to his arrest that he was running away because he had shot somebody in the park and did not want to be arrested. His pursuers at no time shouted any words of menace. He heard them calling out, “Catch him, catch him,” and others shouted, “Stop that man.” It is shown beyond controversy that his pursuers did not desire to kill or injure him, but to arrest him. The defendant testified that he thought his pursuers and those that followed him into the hallway were friends of his brother’s assailants determined upon doing him personal injury. One of his brother’s assailants had staggered back at the time that he was shot by the defendant, and his companion remained with him. It does not appear that the defendant saw any friends of his brother’s assailants in the park. Sechler and Sellick were on Thompson street, more than a block away from the scene of the occurrences in the park. Defendant by special effort dodged them in the street in running toward the hallway, and they were the two that first entered the hallway following him. The jury could have found from this testimony that the defendant ran from the park and into the hallway to avoid arrest, and that at the time he shot Sechler there was no reasonable ground to apprehend a design on the part of Sechler to do the defendant great, or any, personal injury. The question as to whether the defendant in shooting Sechler was acting in self-defense was clearly one for the jury. ( People v. Constantino, 153 N.Y. 24; People v. Filippelli, 173 N.Y. 509; People v. Rodawald, 177 N.Y. 408; People v. Broncado, 188 N.Y. 150.)

The jury were in no way misled or confused by the testimony of what occurred in the park. The reason for admitting such testimony was stated by the court from time to time as it was received, and in the charge to the jury the court say; “I have allowed the people to prove that the defendant discharged a loaded firearm at a human being in Washington Park for the purpose of showing that a felony had been committed and that the defendant was liable to an arrest if such a crime had been committed by him. The people claim that this evidence is material for the purpose of showing the motive and the intent of the defendant at the time that he was endeavoring to escape arrest. That is to say that he intended to shoot any person who attempted to prevent his escape. It was not admitted for the purpose of proving this defendant guilty of the particular crime charged so that act should militate against him upon this charge, but it was admitted for the purpose indicated by me and for no other purpose.”

It is not necessary to constitute murder in the first degree that a person should deliberate and premeditate upon his design to effect the death of another for any specified period of time. The defendant had evaded capture by running five hundred and fifty feet. From his own testimony it appears that he chose his position behind the angle in the hallway and near the staircase and afterwards took his revolver from his pocket. Assuming that the defendant did not decide to shoot and kill his pursuers until he stopped in the hallway, there was time for him, though brief, to deliberate and meditate upon his design after he concluded to stop and while he removed the revolver from his pocket and in his deliberately aiming for the purpose and with the intent of killing Sechler. ( Leighton v. People, 88 N.Y. 117; People v. Majone, 91 N.Y. 211; People v. Schuyler, 106 N.Y. 298; People v. Ferraro, 161 N.Y. 365; Peoplev. Boggiano, 179 N.Y. 267; People v. Conroy, 97 N.Y. 62; People v. Johnson, 139 N.Y. 358; People v. Rodawald, 177 N.Y. 408; People v. Kennedy, 159 N.Y. 346; People v. Del Vermo, 192 N.Y. 470.)

The court, in the charge to the jury, says: “Now if you find from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant realizing that he had fired several shots from a loaded pistol at a human being, and that he was liable to arrest therefor, and that he was endeavoring to escape from a lawful arrest, and that his intention was to kill any person who should attempt to prevent his escape, and that he deliberated and premeditated upon that intent to effect the death of any person pursuing him for the purpose of lawfully arresting him, and that in discharging the loaded pistol at Stechler he did so from a deliberate and premeditated design to effect the death of Sechler, then you may find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree.”

When the commission of a homicide by the person accused has been shown, it is the province of the jury to say from the facts and circumstances surrounding it, unless they clearly repel the idea of deliberation and premeditation, what the character of the act really was and the degree of crime which should be attached to it. ( Peoplev. Conroy, supra.)

After Sechler arrived at the hospital he made a statement in which he said that he believed that he was about to die and that he had no hope of recovery, and then briefly described the pursuit of the defendant and the shooting by him. Oral testimony of such statement was received subject to objections and an exception by the defendant. When the statement was made Sechler was mortally wounded. It clearly appears that he appreciated that recovery was impossible and that his death was imminent, and he did in fact die shortly after such statement was made. Such a statement is admissible as a dying declaration. ( People v. Del Vermo, 192 N.Y. 470.) The statement so made by Sechler was given in evidence before it was known that the defendant would take the stand in his own behalf. The defendant as a witness testified to substantially everything related by Sechler, and the defendant was, therefore, not prejudiced by Sechler’s statement even if it had been improperly received.

During the evening after the shooting the defendant was questioned by an assistant district attorney and his answers were taken by a stenographer with the aid of an interpreter. Before he was questioned he was told that anything that he said could be used against him. There was nothing in his answers materially different from the testimony given by him on the trial, except that in his answers to the assistant district attorney he repeatedly stated that he ran away from the park and into the hallway to avoid arrest, and he did not then assert or claim that any one shot at him in the hallway. Oral evidence of the defendant’s statements to the assistant district attorney were given in evidence in rebuttal after the defendant gave his testimony on the trial. No objection was made to the introduction of such oral evidence, and the stenographer’s minutes of the interview were received in evidence after the court referring to the minutes said to the defendant’s counsel, “You make no objection except that you dispute that what is contained in this record was stated by the defendant?” And to which question the defendant’s counsel answered, “Yes, sir, that is all.”

Other alleged errors are urged by the defendant. A careful examination of the record, however, satisfies us that no error was committed on the trial and that the verdict is supported by the evidence.

The judgment of conviction should be affirmed.

CULLEN, Ch. J., GRAY, EDWARD T. BARTLETT, HAIGHT, WERNER and HISCOCK, JJ., concur.

Judgment of conviction affirmed.

December 18, 1908 Appellate Court decision

In the end the Appellate Court decision balanced the two realities and determined that the court had not unduly influenced the jury by including evidence from the events in the park that had a direct bearing on disproving Governale’s contention of self defense.

This was an unusual case in law and in life. The unlikely chain events that unfolded during a five minute period before sunset on the evening of April 14, 1907 was chaotic, tragic and ultimately irreversible. During these five minutes there were a dozen opportunities for events to have unfolded just a little differently to interrupt the sequence and prevent the tragic outcome. One after another, each of these opportunities failed. The result is permanently etched in our family history.

The justice system of the era did not fail. Lawyers, judges, the police, witnesses, and jurors–perhaps 50 people could be named or inferred from the trial documentation alone–all conducted themselves with the utmost integrity to achieve a swift result in accordance with the law as it existed at the time.

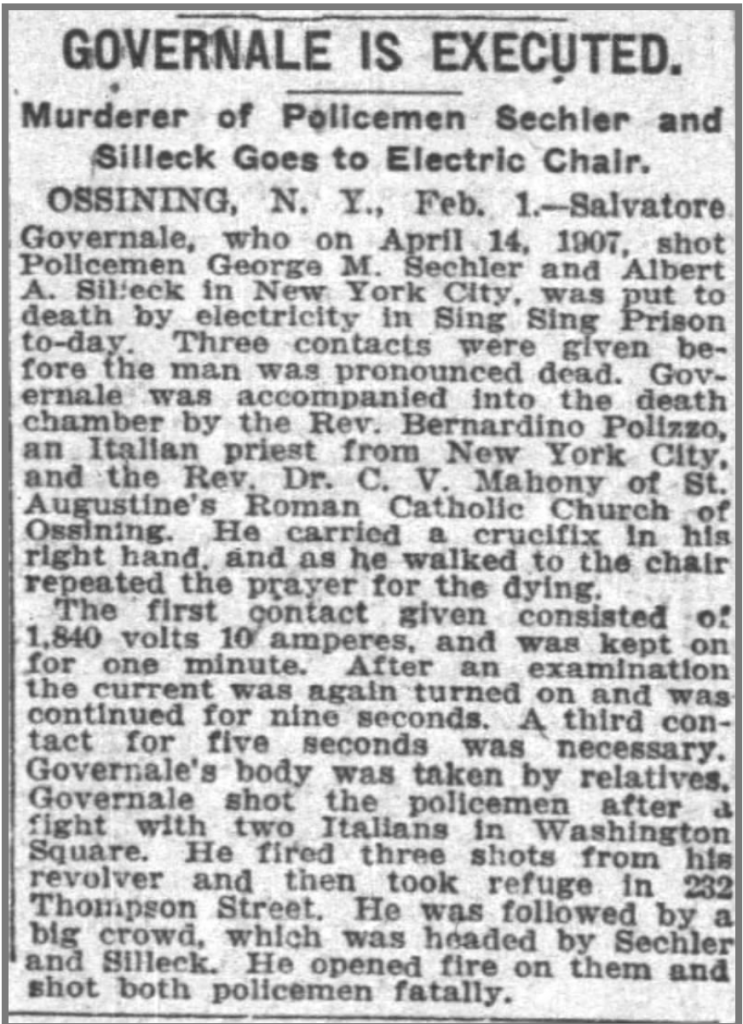

Salvatore Governale was put to death in the electric chair at Sing Sing prison in Ossining, New York on Feb 1, 1909, less than 22 months after the murders were committed.