On August 6, 1866, the General Sherman, an armored and armed side-wheel steamer schooner left Cheefoo, China on a trading mission to Korea, carrying a cargo of cotton, tin and glass. The ship sailed under the United States flag although the venture was undertaken by a British company, Meadows and Co, based in China, and the only Americans aboard were the Captain Page and the Chief Mate Wilson. Two other westerners aboard were the ship’s owner, a British trader named W. B. Preston and Robert Thomas, a Welsh Protestant missionary serving as a translator. Sixteen Chinese and Malaysian sailors made up the remainder of the crew.

On August 6, 1866, the General Sherman, an armored and armed side-wheel steamer schooner left Cheefoo, China on a trading mission to Korea, carrying a cargo of cotton, tin and glass. The ship sailed under the United States flag although the venture was undertaken by a British company, Meadows and Co, based in China, and the only Americans aboard were the Captain Page and the Chief Mate Wilson. Two other westerners aboard were the ship’s owner, a British trader named W. B. Preston and Robert Thomas, a Welsh Protestant missionary serving as a translator. Sixteen Chinese and Malaysian sailors made up the remainder of the crew.

This was a period of cautious isolation in the latter decades of Korea’s Joseon dynasty. Against a backdrop of centuries of conflict with its Chinese and Japanese neighbors, and now seeing increasing presence of Europe and the United States in search of exploiting Asian markets, Korea intended to keep a low profile in the region, to conceal itself from the west in the midst of its larger, more powerful neighbors. There had been a few earlier successful western trading missions to Korea, but it remained mostly unknown territory, shrouded in mystery.

The General Sherman entered the Taedong River on Korea’s west coast on August 16, sailing upriver toward Pyongyang. They stopped at the Keupsa Gate, expressing their intentions for a trade mission. The Koreans provided the ship with provisions, but rejected the trade offers. Against Korean orders, the General Sherman continued up river until stranding at Yangjak island near Pyongyang, where they were rebuked by the Pyongyang governor and ordered to wait for a decision on their fate. The situation escalated further when a Korean official, coming to the ship at the invitation of Captain Page, was taken prisoner on board. By late August the ship received official orders to depart or be killed, but they were stranded on a sandbar in the temperamental river currents, unable to maneuver.

On August 31, the General Sherman fired its canons into soldiers and civilians on shore, killing many. The Koreans responded to shots from the ship with fire arrows and rocks over several days. Eventually the Pyongyang governor ordered attacks by small boats. It was small boats set ablaze and drifted toward the General Sherman which finally succeeded in setting it ablaze. The westerners and some of the crew perished aboard. Other crew and the Korean hostage escaped and made it to shore.

About the same time as the destruction of the SS General Sherman, the Koreans conducted a mass execution of Christians and several French Jesuit Priests. Neither a punative expedition carried out by the French later in 1866 nor an American mission looking for answers and apologies in 1871 yielded much in the way of tangible results. In 1882 a treaty between the United States and Korea laid the foundation for the first diplomatic relations between the two countries.

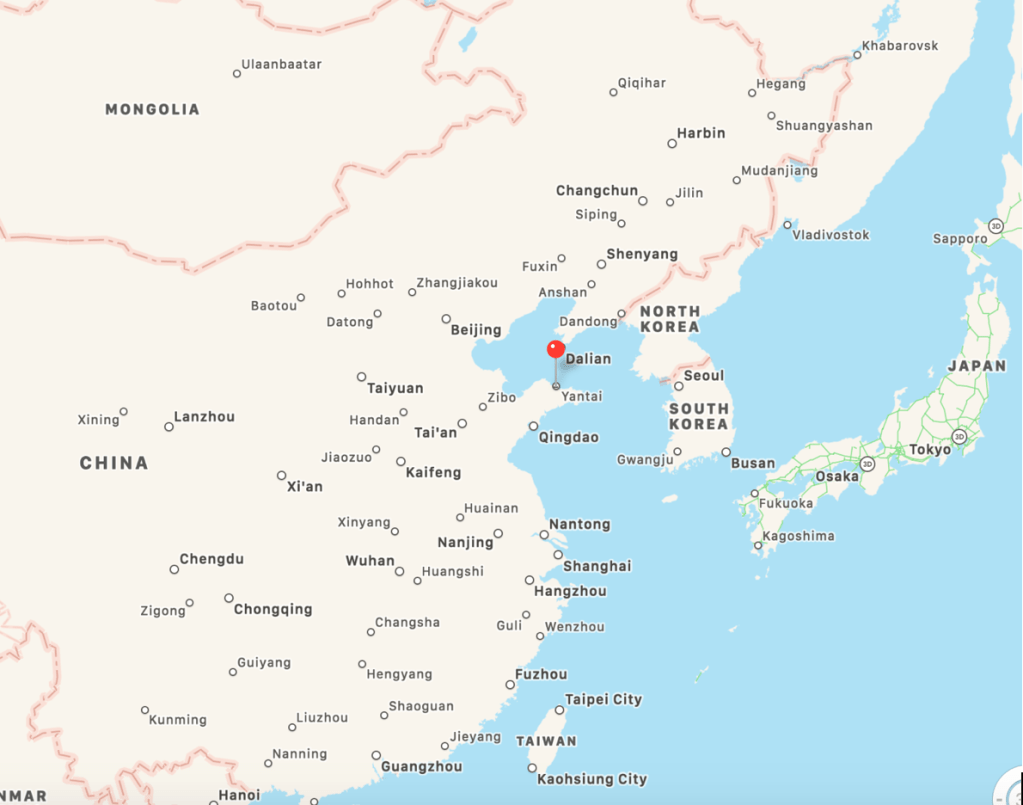

In August 1866 Edward Sandford had been at his post as United States Consul to Cheefoo (today called Yantai), China for a little less than a year. A quick glance at the map shows that he may have been the United States official closest to the events in Korea related to the General Sherman. The entrance to the Taedong River is on the west coast of what is now North Korea, about 50 miles north of the border with South Korea. It is about 150 miles across the East China sea from Cheefoo.

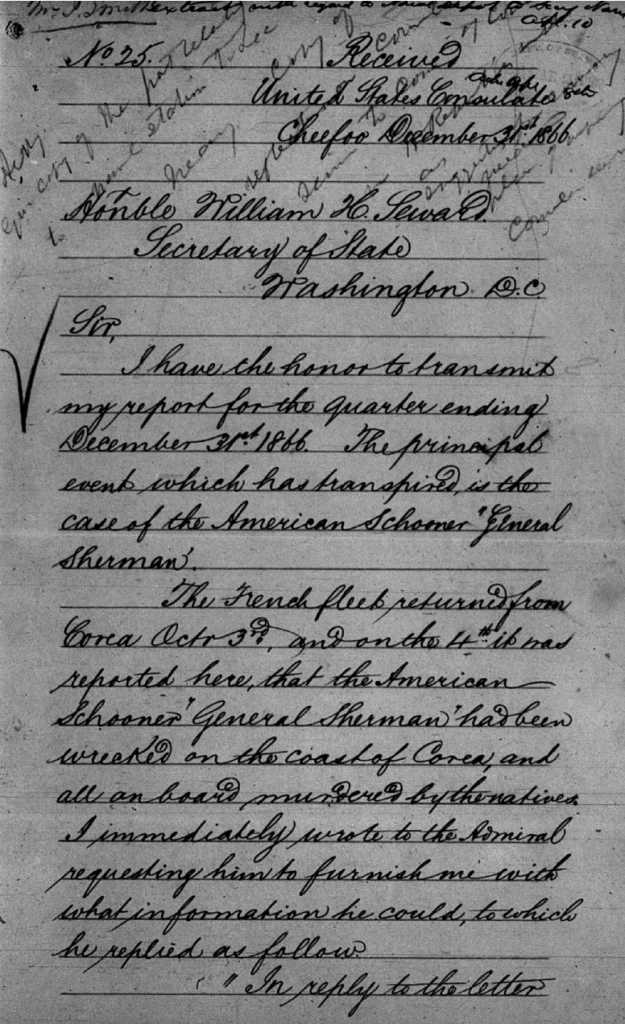

As word of the General Sherman incident made it back to Cheefoo, Edward must have recognized his duty to report as much as he could back to Seward in Washington. His December 1866 quarterly report includes a twelve page letter on the matter, and is replicated and transcribed below in its entirety.

Honorable William H. Seward, Secretary of State, Washington D.C.

Sir,

I have the honor to transmit my report for the quarter ending December 31st, 1866. The principal event which has transpired is the case of the American Schooner “General Sherman”.

The French fleet returned from Corea October 3rd, and on the 4th it was reported here that the American Schooner “General Sherman” had been wrecked on the coast of Corea, and all on board murdered by the natives. I immediately wrote to the Admiral requesting him to furnish me with what information he could, to which he replied as follow.

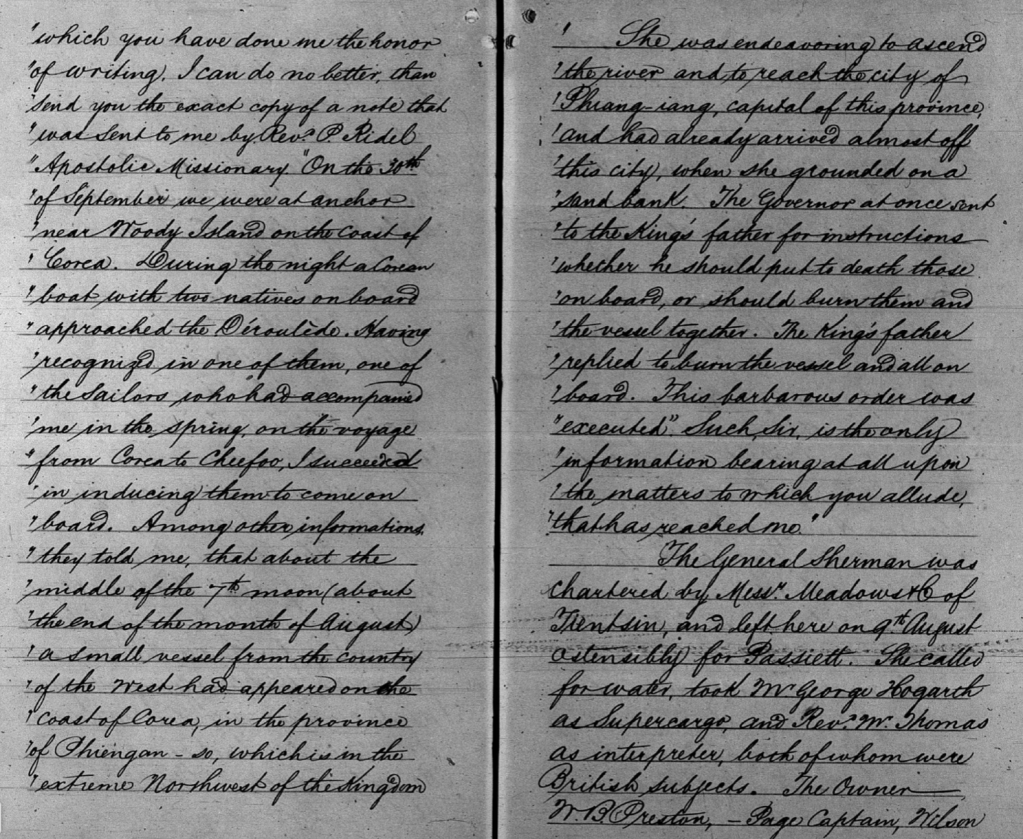

“In reply to the letter which you have done me the honor of writing, I can do no better than send you the exact copy of a note that was sent to me by Rev. P. Ridel Apostolic Missionary. ‘On the 30th of September we were at anchor near Woody Island on the coast of Corea. During the night a Corean boat with two natives on board approached the Déroulède. Having recognized in one of them, one of the Sailors who had accompanied me in the spring on the voyage from Korea to Cheefoo, I succeeded in inducing them to come on board. Among other informations they told me that about the middle of the 7th moon (about the end of the month of August) a small vessel from the country of the West had appeared on the coast of Korea, in the province of Phiengan—so which is in the extreme Northwest of the Kingdom.

“‘She was endeavoring to ascend the river and to reach the city of Piang-iang, capital of this province, and had already arrived almost off this city, when she grounded on a sand bank. The Governor at once sent to the King’s father for instructions whether he should put to death those on board, or should burn them and the vessel together. The King’s father replied to burn the vessel and all on board. This barbarous order was executed.’ Such, Sir, is the only information bearing at all upon the matters to which you allude, that has reached me.”

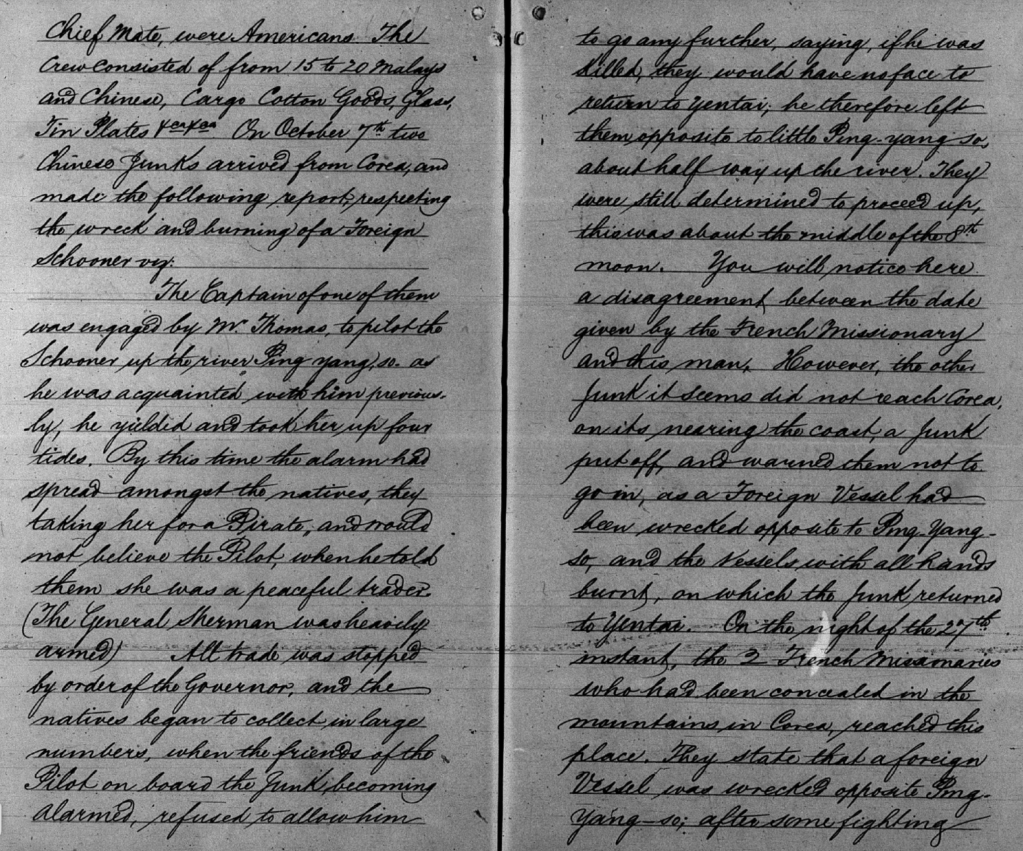

The General Sherman was chartered by Messr. Meadows & Co. of Tientsin, and left here on 9th August ostensibly for Passiett. The called forwater, took Mr. George Hogarth as Supercargo, and Rev. Mr. Thomas as interpreter, both of whom were British subjects. The Owner, M. B. Preston, Page, Captain, Wilson Chief Mate, were Americans. The crew consisted of from 15 to 20 Malays and Chinese, Cargo Cotton Goods, Glass, Tin Plates ??. On October 7th two Chines junks arrived from Korea, and made the following report respecting the wreck and burning of a Foreign Schooner viz:

The Captain of one of them was engaged by Mr. Thomas to pilot the Schooner up the river Ping Yang, so as he was acquainted with him previously, he yielded and took her up four tides. By this time the alarm had spread amongst the natives, they taking her for a Pirate, and would not believe the Pilot, when he told them she was a peaceful trader. (The General Sherman was heavily armed.) All trade was stopped by order of the Governor, and the natives began to collect, in large numbers, when the friends of the Pilot on board the Junk, becoming alarmed, refused to allow him to go any further, saying, if he was killed, they would have no face to return to Yentai; he therefore left them opposite to little Ping-Yang so, about halfway up the river. They were still determined to proceed up, this was about the middle of the 8th moon. You will notice here a disagreement between the date given by the French Missionary and this man. However, the other Junk it seems did not reach Corea, on its nearing the coast, a Junk put off and warned them not to go in, as a Foreign Vessel had been wrecked, opposite to Ping-Yang-so, and the vessels with all hands burnt, on which the Junk returned to Yentai. On the night of the 27th ??, the 2 French Missionaries who had been concealed in the mountains in Korea, reached this place. They state that a foreign vessel was wrecked opposite Ping-Yang–so; after some fighting between the natives and those on board the Schooner, the natives succeed by strategy in drawing the men on shore, when they were surrounded and their hands tied behind their backs. They were then made to kneel down on the shore, and were beheaded. The Missionaries report they were 20, thus put to death.

Inquiry now arises, what has been done with the rest. Mr. Moore informed me that the crew consisted of nearly 20 while there were in addition five Europeans besides their servants. It may be that the Coreans, instead of putting them to death, kept them prisoners thinking that they might be enabled to use them in some way, on arrival of the French forces.

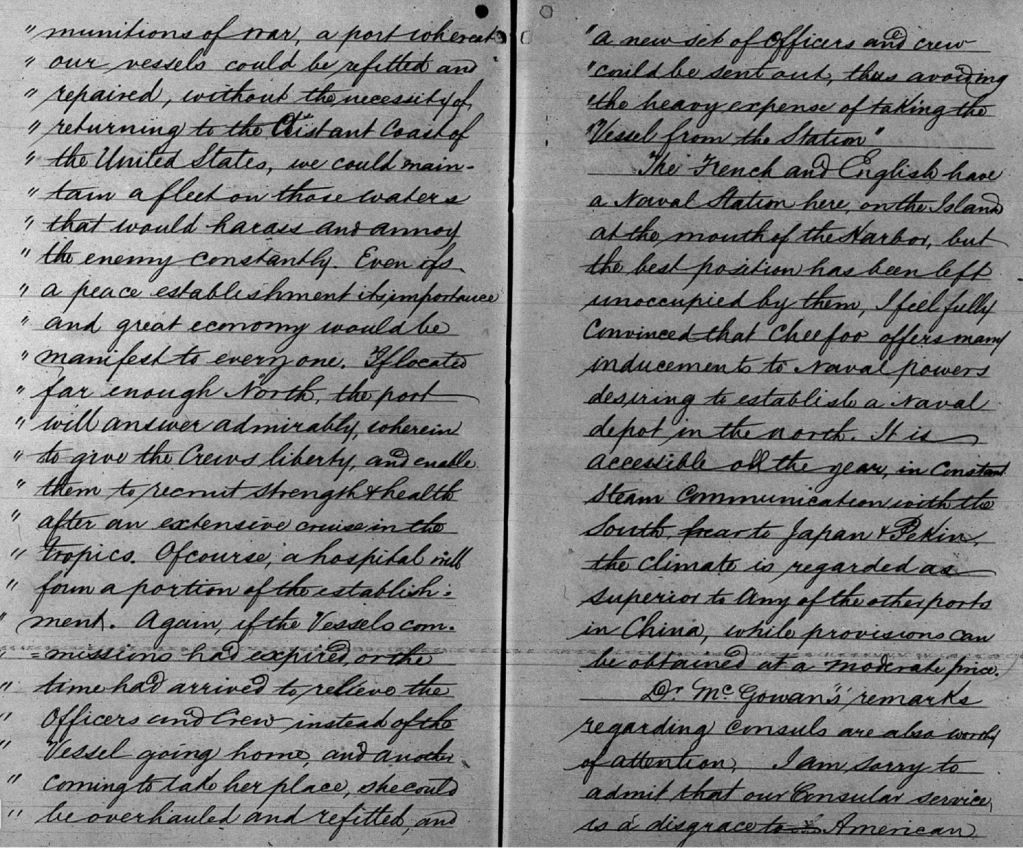

A speech made by Dr. McGowan in San Francisco is one which I feel well merits the attention of the Government, he says “The Government of the United States should follow the example of other great powers and establish at the earliest possible moment, naval station on the Coast of China and Japan. In the event of a War between the United States and other Maritime Power, one of the most important points wherein the commerce of that power could be seriously annoyed will be that Indian Ocean and China Seas, but to do this a powerful squadron have to be employed, and this could not be done if we possess no base of supplies nearer than our nearest home port, which port would be San Francisco, had we however a Naval Station, a depot of stores and munitions of war, a port whereat our vessels could be refitted and repaired, without the necessity of returning to the distant coast of the United States, we could maintain a fleet on those waters that would harass and annoy the enemy constantly. Even as a peace establishment the importance and great economy would be manifest to everyone. If located far enough North, the port will answer admirably, wherein to give the crews liberty, and enable them to recruit strength and healths after an extensive cruise in the tropics. Of course, a hospital will form a portion of the establishment. Again, if the Vessels commissions had expired or the time had arrived to relieve the officers and crew instead of the vessel going home, and another coming to take her place, she could be overhauled and refitted, and a new set of officers and crew could be sent out, thus avoiding the heavy expense of taking the vessel from the station”

The French and English have a Naval station here, on the island at the mouth of the harbor, but the best position has been left unoccupied by them, I feel fully convinced that Cheefoo offers many inducements to Naval powers desiring to establish a Naval depot in the north. It is accessible all the year, in constant steam communication with the South ?? to Japan and Pekin, the climate is regarded as superior to any of the other ports in China, while provisions can be obtained at a moderate price.

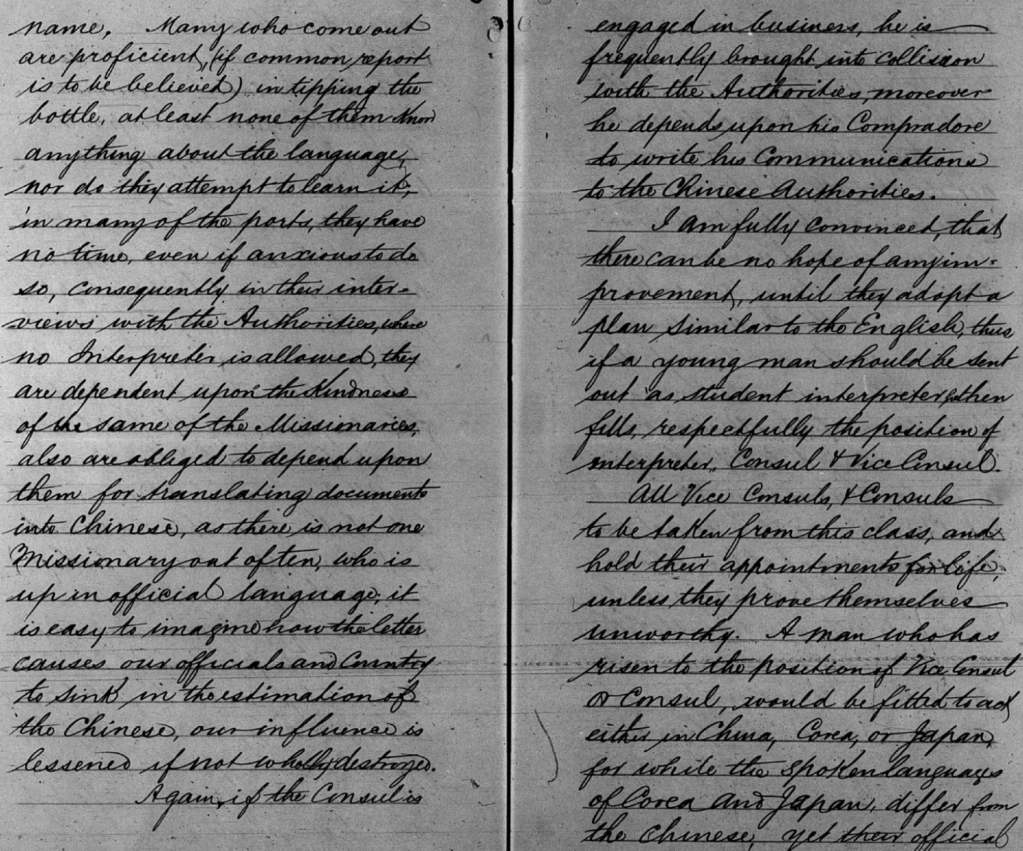

Dr. Mc Gowan’s remarks regarding consuls are also worthy of attention. I am sorry to admit that our Consular service is a disgrace to American name. Many who come out are proficient (if common report is to be believed) in tipping the bottle, at least none of them know anything about the language nor do they attempt to learn it, in many of the ports they have no time, even if anxious to do so, consequently in their interviews with the Authorities, where no interpreter is allowed, they are dependent upon the kindness of the same of the missionaries, also are obliged to depend upon them for translating documents into Chinese, as there is not one missionary out of ten who is up in official language; it is easy to imagine how the letter causes our official and country to sink into the estimation of the Chinese, our influence is lessened if not wholly destroyed.

Again, if the Consul is engaged in business, he is frequently brought into collision with the authorities, moreover he depends upon his Commadore to write his communications to the Chinese authorities.

I am fully convinced that there can be no hope of any kind improvement until they adopt a plan similar to the English, thus if a young man should be sent out as student interpreter he then fills, respectfully the position of interpreter, Consul and Vice Consul.

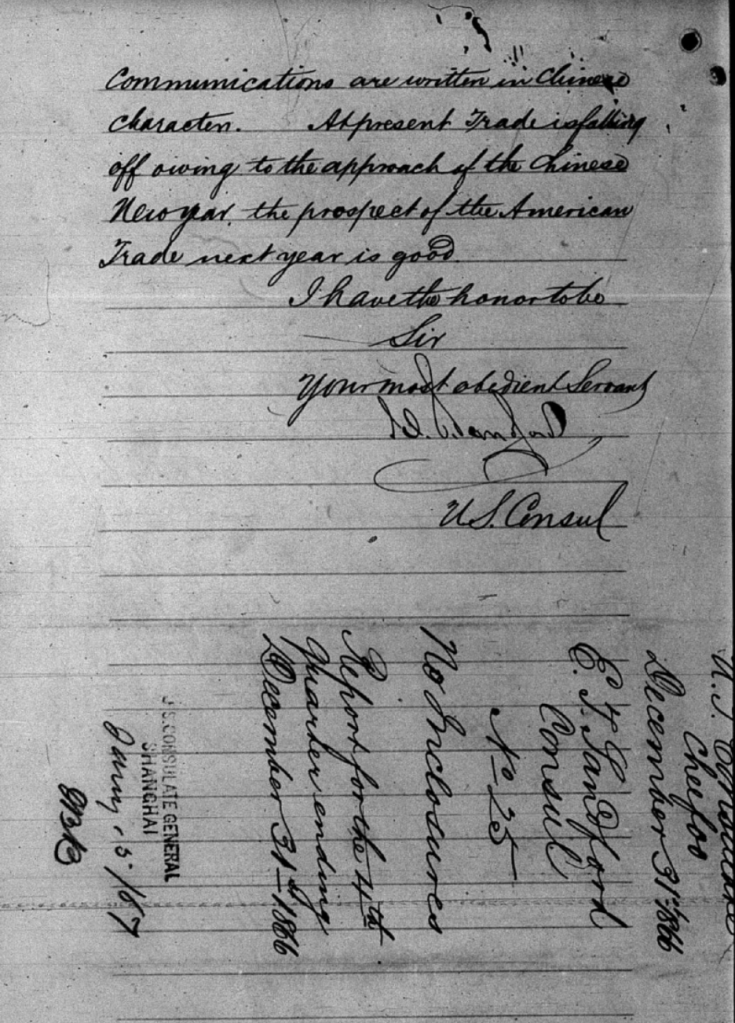

All Vice Consuls and Consuls to be taken from this class, and hold their appointments for life unless they prove themselves unworthy. A man who has risen to the position of Vice Consul or Consul would be fitted to act either in China, Corea, or Japan, for while the spoken languages of Corea and Japan differ from the Chinese, yet their official communications are written in Chines characters. At present trade is falling off owing to the approach of the Chinese New Year, the prospect of the American Trade next year is good.

I have the honor to be, Sir, your most obedient servant

E. Sandford, U.S. Consul

Transcription of Edward Sandford’s letter to William Seward, January 1, 1867, courtesy of National Archives

This letter is remarkable for several reasons.

Edward’s account is in close agreement with the historical record of the General Sherman incident, the coinciding executions of the Christians and Jesuit Priests, and the subsequent French expedition attempting to achieve retribution.

The letter gives clear indications of Edward’s general ideas and state-of-mind regarding his post as Consul. He had the temerity to use his report of the incident to William Seward to offer two specific pieces of advice to the Secretary of State: his views on the need to establish a strategic naval base in China, and, most remarkably, his candor on shortcomings of the United States’ diplomatic missions in China, Korea, and Japan.

The Doctor McGowan quoted to Seward by Edward appears to have been a Baptist Missionary who served in the Ningpo (Ningbo on today’s maps, on the coast of China about 500 miles south of Cheefoo) Mission of the American Baptist Union in the late 1850s. Little information about him came to light in basic searches, but a 1994 publication A History of Christianity in Japan gives enough information on McGowan’s ideas on religion, language and the Orient to realize that Edward had acquired very similar views, some of which he expressed directly to William Seward. Somewhere in Edward’s travels, perhaps even during his first voyage to Asia, Edward had learned of, perhaps crossed paths with, Dr. McGowan and had become some sort of disciple.

Along with traders, missionaries were some of the first westerners to have made their way into the Orient as travel there became possible. The promulgation of Christianity in Asia was on the list of objectives considered important by the United States Government at the time, therefore, Edward’s citation of a prominent Baptist missionary probably held some sway with Seward.

Edward’s comments on the state of the diplomatic services in China and the region seem to be a clear indication of his dissatisfaction with what he had seen in his first year on the job–he viewed some of his peers (and perhaps some superiors) as incompetent, self serving and self dealing men who did not take their responsibilities seriously enough. His religious beliefs (and/or his fellow diplomats’ lack thereof) seem to have been part of this.

The contents of this letter, consistent with the fact that Edward would later pursue a completely new career path as a Baptist Minister, are indications that he felt that his post in China, important as it was, did not give him the latitude needed to accomplish things at the level he felt to be his true calling.

Edward pushed the envelope with this letter to Seward, far beyond what a basic report of his findings on the General Sherman incident would have called for. He must have given the matter a great deal of thought, and these thoughts must have continued percolating in him over the next two years of his tenure in China.

From the point of view of world history and the emerging relationship between the United States and China in the 1860s, Edward was in the thick of it.

The June 1858 Treaty of Tianjin (under President James Buchanan) put an end to the Second Opium War involving China, Russia, Britain and the United States. Although classified by the Chinese as one of the “unequal treaties” of the era, it opened trading relationships in China and probably is what brought about the 1860/1861 trade mission undertaken by Edward’s ship-owner uncle, Edward’s first Asian voyage.

The post of U.S. Consul to CheeFoo must have existed because of the Tianjin Treaty and Lincoln and Seward’s desires to pursue the American interests opened up by it.

The General Sherman incident and others like it, would have posed challenges to William Seward and the United States in moving forward with plans for developing relations and trade in the region. In July 1868 the United States and China signed the Burlingame Treaty (also known as the Burlingame-Seward Treaty expanding the Tianjin agreement. Anson Burlingame, previously Lincoln’s appointed minister to China, negotiated the treaty with Seward on behalf of China. The treaty, one of Seward’s final signature accomplishments as Secretary of State, represented a shift away from previous imperialistic efforts of the United States toward a fairer, more cooperative relationship. From China’s viewpoint, the treaty empowered them to limit interference in their national affairs in exchange for greater access to its markets.

China policy being such an important priority for Seward and the United States, it seems evident that Edward Sandford’s correspondence, particularly on the key topics like the General Sherman incident, would have been been studied by Seward and would have influenced his diplomatic efforts in the region, including his negotiations for the Burlingame-Seward treaty.

Edward was only 27 years old when the treaty was signed. His story is to be continued.

One thought on “The General Sherman Incident”