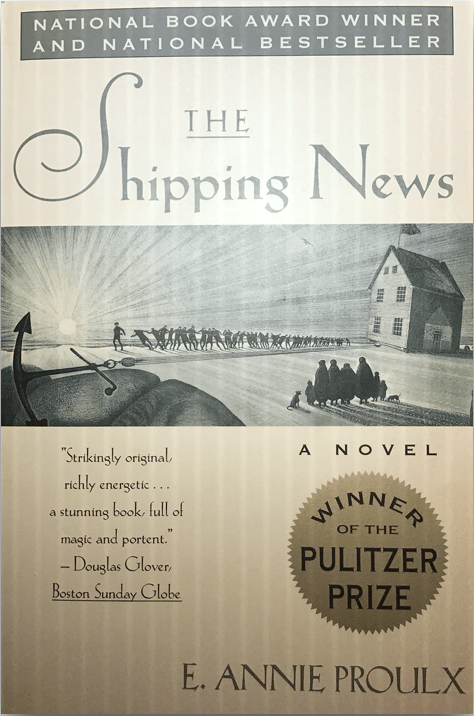

The Shipping News, a novel by E. Annie Proulx published in 1993, follows the life of Quoyle, a childhood immigrant from Newfoundland who falls on hard times and decides to move back to his homeland with his young children and his aunt, Agnis Hamm. On the journey, Quoyle discovers truths about his former homeland, his family, and himself. He learns of the wonders of Newfoundland as well as its dark secrets. Agnis, who has firsthand experience with some of these dark secrets, balances support of her nephew with her need to exorcize her own demons from the past.

The Shipping News, a novel by E. Annie Proulx published in 1993, follows the life of Quoyle, a childhood immigrant from Newfoundland who falls on hard times and decides to move back to his homeland with his young children and his aunt, Agnis Hamm. On the journey, Quoyle discovers truths about his former homeland, his family, and himself. He learns of the wonders of Newfoundland as well as its dark secrets. Agnis, who has firsthand experience with some of these dark secrets, balances support of her nephew with her need to exorcize her own demons from the past.

The book was made into a movie of the same title in 2001 starring Kevin Spacey as Quoyle and Judi Dench as Agnis.

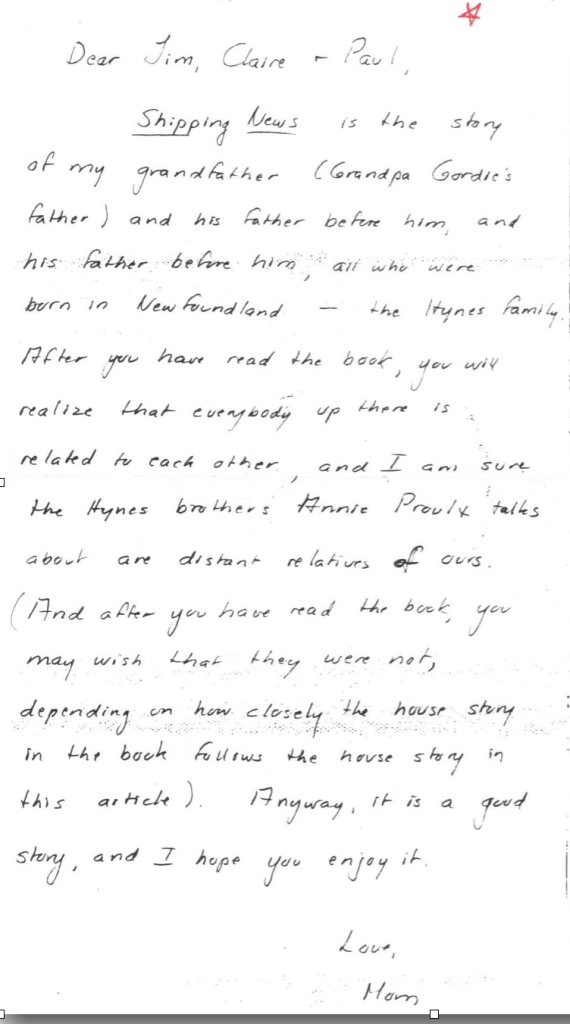

The potential relationship of the story with our ancestry first came to light in 1997 or 1998 with a note from our mother telling us about it in fairly certain terms, and giving us some warning about the dark side.

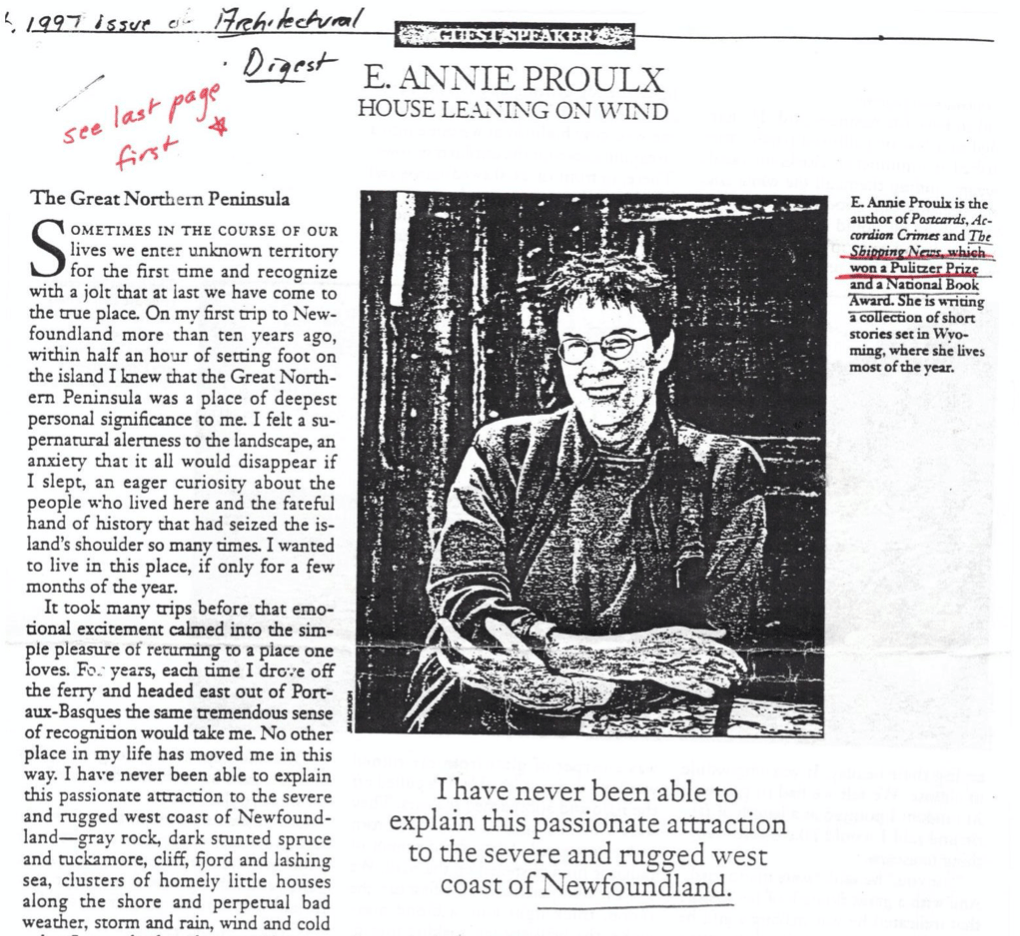

The note was attached to a copy of a 1997 non-fiction article from Architectural Digest, also written by Proulx, describing her experiences in Newfoundland leading to writing the book. The article, titled House Leaning on Wind, describes her efforts to buy and restore a house in northern Newfoundland originally built by members of the Hynes family and passed down several generations of Hynes descendants. With the information in this article, we can ask two questions: did Proulx’s inspiration for the novel include her encounters with the Hynes family? …and… is this the same Hynes family as ours?

Literary Inspiration – Did Proulx’s experiences with a Hynes family on Newfoundland help inspire the book?

House Leaning on Wind describes how Proulx’s fascination with Newfoundland took root over a series of visits, and gives clues on the origins of many of the plot elements in The Shipping News.

Specifically, she explains that in the years prior to writing the book, she was drawn to Newfoundland by a series of quasi-cosmic events, fell in love with the place, and decided to buy a house there. She found an old house near Gunner’s Cove, near the extreme end of the island’s northern peninsula.

Although the price of the house was, in Proulx’s words, “less than the cost of an ordinary sofa,” there were problems with getting clear title to the property. Newfoundland is not known for its record keeping, something I have found in my own genealogical research. It only became a part of Canada in 1949, and its history is comprised of centuries of fisherman eking out a living in the harshest imaginable conditions. Informal property transfers within families were not uncommon over the generations.

Proulx explains that in order to establish the seller’s clear title to the property she hired Catherine Allen-Westby, a lawyer from Corner Brook (the closest thing to a large town in the vicinity of Gunner’s Cove but still 150 miles away) to research the property, conduct interviews, and piece-together a legal case for the ownership of the property. The house had been built around 1918 by brothers Lawrence and John Hynes who lived there most of their lives (they died in 1973 and 1975). Later, their niece Bridget Young and her family lived with them and built a second house on the property. The houses passed from the Hynes brothers to Bridget and finally to Bridget’s daughter Shirley Young, who wished to sell the property to Annie Proulx.

It must be noted that Proulx’s timeline in House Leaning on Wind is not completely consistent or clear–although it is a work of non-fiction, one can see that some artist’s license likely crept-in. The Shipping News was published in 1993, but her final legal claims for title of the house were filed in 1995. Despite the time delay, there is a lot about Proulx’s house buying adventure that clearly seems to have made it into the book. It could be that Proulx’s early Newfoundland experiences informed both her novel and the later magazine article. But because of the specificity of many of the references in the novel I believe it is possible that Proulx’s experiences with the house overlapped the writing of the novel. She may have bought the house informally and begun restoring and using it for a while before the need to address the legal issues of title became completely clear.

Let’s look at some of the similarities between the novel and Proulx’s experiences with the Hynes’. In House Leaning on Wind, Proulx describes her discovery of twisted timbers in the foundation of the Hynes home that are strikingly similar to boatbuilding techniques used by Newfoundlanders who build boat keels from naturally curved trees, giving the boats a great deal of added strength. Annie and her carpenters concluded that the use of similar techniques in the foundation of the Hynes house contributed to its longevity. Compare the following quotes…

With these serious underpinning defects, it was a mystery how the roofline had stayed level and the house square.

House Leaning on Wind, by Annie Proulx, Architectural Digest, 1997.

“Miracle it’s standing. That roofline is as straight as a ruler,” the aunt said. Trembling.

Aunt Agnis after her return to the family house, The Shipping News, Chapter 5, by Annie Proulx.

In the novel, Quoyle later learns the story of how his ancestors, having committed crimes too heinous even for the rough folks of Newfoundland to tolerate, are banished from the town and their house is dragged by the townspeople to its new location across the frozen ice of the bay. There is no way to prove that this dreamlike scene was inspired by the boat-like, sled-like timbers under the real-life Hynes house, but the idea is compelling.

The Hynes house, like Quoyle’s ancestral family home is indeed a substantial boat ride across the bay. Proulx describes her first encounter with the Hynes house as follows.

For a long time I watched the whales rise and dive. An outboard motor across the bay stuttered dimly. The fog thinned and lifted and then, as through an opened door a crack of brilliant light came over the ocean and illuminated the coast. A mile distant, at the foot of a sloping meadow, I saw a pale, steep-roofed hope, its windows flashing orange in the raw light, alone on the shore with the black spruce rising behind it.

House Leaning on Wind, by Annie Proulx, Architectural Digest, 1997.

Quoyle later learns of the presence of a cousin, Nolan, who still lives and lurks near his ancestral home. After mysterious sightings and finding mysterious objects around his house, Quoyle finds his hermit cousin and tends to him. Eventually Quoyle is compelled to commit Nolan to an asylum where, on a later visit, Nolan reveals to Quoyle his aunt’s dark secret, that Quoyle’s father had violated his sister, Quoyle’s aunt, in Newfoundland, when they were young.

I have no evidence of improper behavior on the part of John or Lawrence Hynes, but it is difficult not to compare cousin Nolan skulking around Quoyle’s house with the Hynes brothers living in the old house nearby his niece in the newer house in their final years in the 1970s. According to the legal depositions collected to build the case for title to the house, Lawrence Hynes became paralyzed and moved into the newer house with his niece Bridget Young and her family for the final years of his life, not unlike Quoyle caring for his aging cousin.

So as to the question of whether the family and house of Lawrence and John Hynes served as literary inspiration for The Shipping News, we have mixed indications. The similarities are compelling and hard to dismiss, but we also have to twist and turn a bit to explain discrepancies in Proulx’s time line.

The Search for a Genealogical Connection – Is the Hynes family that Proulx encountered on Newfoundland a branch of our Hynes family

To begin, we must note that Gunner’s Cove, the site of the house, is not quite in the same area of Newfoundland as our ancestors—the two areas are about 75 miles apart. Somebody would have had to have made a significant move from the mainstream of our Hynes ancestors, who predominately moved from east to west over several generations along the north shore of Newfoundland, but not on the northern peninsula. This is possible given that generations of Newfoudlanders lived off the fisheries and pursued work where they could get it.

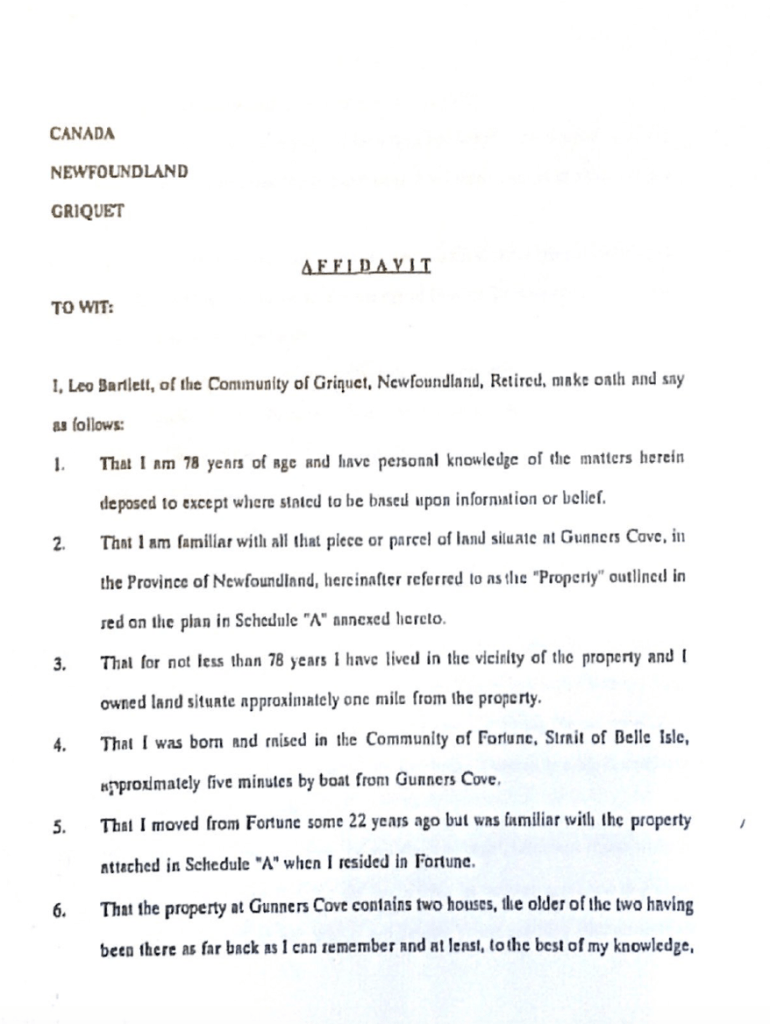

In 2019, inspired by Proulx’s words “these beautiful documents were miniature histories of the Hynes brothers,” I wrote to both Proulx (via her publisher) and Catherine Allen-Westby to ask if there was any way to obtain copies of the 1995 paperwork. Mom recently told me that she once also tried writing to Proulx. Neither of us got a response from Proulx, who had long since moved-on to Wyoming and writing Brokeback Mountain. But I did get a response from Allen-Westby. She had long been a judge in the Newfoundland Provincial Courts, in fact she let me know that she was on the verge of retirement. She graciously found the public record legal documents that she had submitted in 1995 on behalf of Proulx, and sent me a copy.

The package is 23 pages long. It primarily consists of three similar depositions, one from Shirley Young, the owner and prospective seller of the house and two other members of the community of sufficient age and standing to be credible witnesses as to the historical ownership of the property, Leo Bartlett and Lewis Elms.

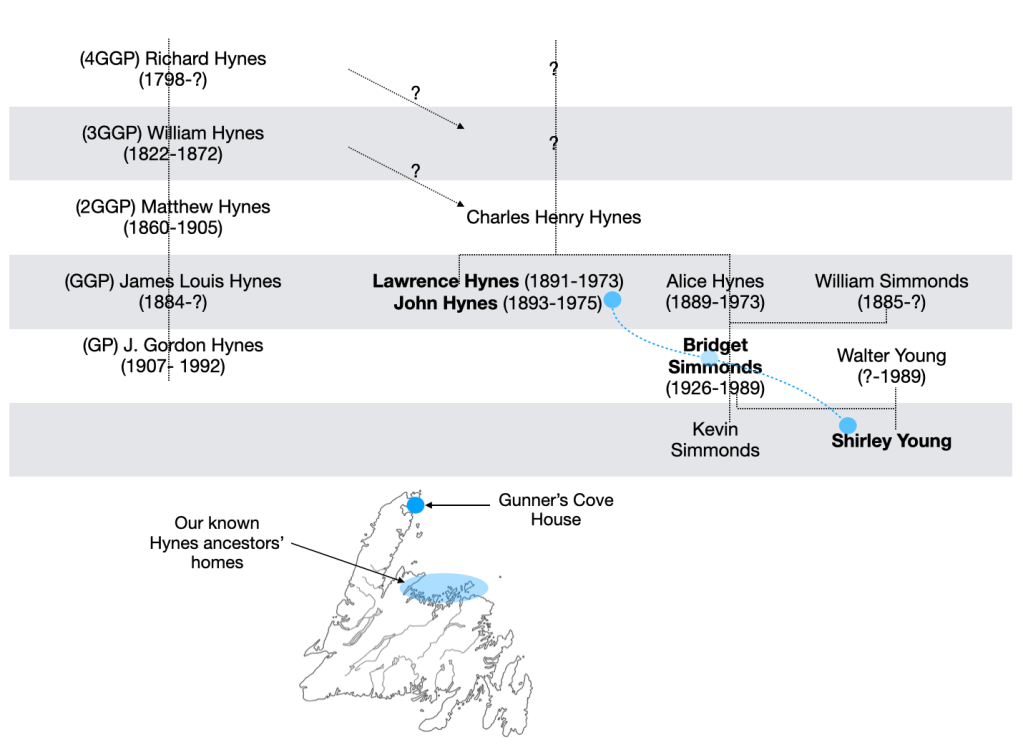

The information in the affidavits is sufficient to piece together the ancestry of Shirley Young back to her great grandfather Charles Henry Hynes. Two of his sons, John and Lawrence Hynes lived in the house since about 1918, and eventually the title passed down to Shirley Young.

In a previous post, we established our Hynes ancestry in Newfoundland as best as could be determined. This is shown side by side with the ancestry of Shirly Young and her great uncles Lawrence and John Hynes in the following diagram.

Unfortunately, this is as far as the records take us in trying to connect the two Hynes families. Just as we previously pushed our own family ancestry back as far as we could to Richard Hynes, I found no record of the ancestry of Charles Henry Hynes. But neither can we disprove the link—the diagram indicates that there are possible ways that the families could have separated in Newfoundland, or possibly earlier in Britain.

In terms of comparing generations between the two Hynes families, John and Lawrence Hynes were roughly the same age as our great grandfather James Louis Hynes. James Louis was born in 1884, Lawrence in 1891 and John in 1893. James Louis had siblings the same age as Lawrence and John. James Louis and Lawrence/John are not brothers since we are confident we know all of James Louis’ family. Similarly, they are probably not cousins, since we are pretty sure we know everyone in William Hynes’ family. But a second cousin or higher relationship is possible because we don’t know very much about our ancestor Richard Hynes, and we don’t know who Charles Henry Hynes father was.

A note on the time shift between fiction and reality. Like Quoyle, James Louis was brought to the United States with his family when he was a boy, but a half century earlier. So some of the Newfoundland historical background in The Shipping News, such as the large scale importation of workers to work in Canada under near slave-like conditions, does not pertain to our family’s ancestors but occurred after they had already immigrated to New Jersey and New York.

So we cannot prove the two Hynes families are linked. But recall that in the earlier post we said that the resident population of Newfoundland grew from an estimated five thousand in 1765 to ten thousand in 1785 to forty thousand in 1815. Richard Hynes was born around 1798 when the population was maybe twenty thousand, the size of a small town, and the population of the remote far north of Newfoundland would be a fraction of this. With such small numbers, Mom’s statement about everyone up there being related to each other does not seem unreasonable, particularly between two families with the same last name living within 75 miles of each other.

So, is The Shipping News about our ancestors?

Approaching the question logically, dividing it into two smaller questions and examining all the available evidence resulted in a firm maybe for both questions. There may be more genealogical evidence out there–I will continue to look–or the answer may be lost to history.

I have gradually realized that there is something deeper fueling my interest (or obsession) with The Shipping News. Whether it is the same Hynes family or not, whether Proulx wrote the book directly based on the Hynes brothers and their house or the similarities are just coincidental and rooted in the general character and history of Newfoundland, the book captures insights about our family that feel important.

The similarities noted previously between Quoyle’s fictional ancestors and Shirley Young’s real ancestors, between the fictional house and the real house are part of it. But there is more, and to fully understand it we have to go back to the story of the secret of Aunt Agnis, the apogee of Proulx’s story line.

I said earlier that I have no evidence that Agnis’ secret about her brother (revealed to Quoyle by his cousin Nolan) was mirrored in any real-life behavior of Lawrence or John Hynes. But I also know that Agnis’s story is very similar to events that took place among our own Hynes ancestors. It is known in our family history that great grandfather James Louis Hynes violated his sister Blanche. As we will see in future posts, his transgressions did not stop there. Agnis’ fictional demons were more than matched by the direct and collateral damages inflicted on several members of our real-life Hynes family. It is this, combined with all the other similarities in The Shipping News, which leads me to conclude that even if the similarities between the novel and our ancestors’ stories are completely coincidental, the novel cannot be seen as anything less than a profound look into the soul of the Hynes branch of our family and their Newfoundland homeland.

The acknowledgement of the parallels between these fictional and real-life dark family secrets seems sufficient grounds for a declaration of truce with my unease with the uncanny similarities between our Hynes ancestry and the Proulx novel. I should mention that I considered other explanations which might best be classified as conspiracy theories, none of which led to anything credible. I looked at the possibility that we have a family link with Proulx–I found none and I now don’t believe one exists. I also asked Mom several times whether the subject of the book ever came up in our extended family when it was published, wondering how it could be that the whole family was not talking about it. The consistent, repeated answer was no, Mom really did just stumble on the article in Architectural Digest–it does make sense that she would have and a subscription to it in the 1990s–and her thoughts either were not shared with the extended family or the family’s secrecy gene kicked-in and quickly suppressed any wider discussion.

Each time I visit the stories of our Newfoundland ancestors and their American descendants I rediscover the same recurring patterns–dates and facts which don’t quite match up vs. coincidences that are so compelling they seem to comport important truths; the contrast between Newfoudland’s geographical beauty and its extreme human toil, suffering and darkness; the conflict between wanting to understand our Hynes family and facing it’s deeply ingrained family secrecy. I expect this to continue through the remainder of the saga of our Hynes ancestors.

I chose the name Bridging the Silences because I wanted to tell stories of our ancestors the only way I felt possible, by bridging known, sometimes scant, facts across large gaps with reason and informed speculation. New variations on the meaning of the phrase keep coming up. Silences can also be the result of deep distrust of government efforts to collect information, as we saw with the early Calderwood family. Silences can come from mistakes in the genealogical record, as we saw with Josephine Sandford Ware’s mistake in identifying the father of Captain Thomas Sandford from several candidates on Long Island.

And silences can be the result of deep-seated family secrecy surrounding the darker chapters of its history.

In all this, we should not forget that The Shipping News is, on the whole, an inspirational story that sheds light on an amazing place with amazing people. Our ancestors, despite their problems, were part of this for more than three generations–very tough people making their livelihoods under conditions that today we can barely imagine. I like The Shipping News because it tells, and emphasizes, this side of the story.

I also like The Shipping News because it gives me cover in confronting the stories of what is certainly our most uncomfortable family branch—trees on the barren landscape to run between and hide behind as I prepare to storm the next hill of truth.

Finally, in the overall patchwork of our family genealogy, the very existence of The Shipping News is an astonishing thing. Our Hynes branch is by far the least researchable of all our family branches, this compounded by the secrecy that surrounds it. Yet, out of nowhere, there is this novel, written by a stranger, looking into the soul of the family as if to say “sorry about the poor state of the genealogical record, but, here is a book to help fill in the gaps and make some sense out of everything.” And, to go with it, a magazine article which says “in case you missed the messages in the book, here is a Rosetta Stone you can use to help decode the messages.” Thank you, Ms. Proulx, for helping to bridge the gaps, even if unintentionally.

Is The Shipping News about our Hynes ancestors? Absolutely.

2 thoughts on “Is The Shipping News about our Hynes ancestors?”