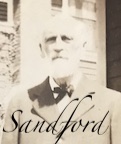

There are big mysteries in genealogical research and there are small ones. Great grandfather Edward Thomas Sandford lived a life spanning 82 years and a half dozen major chapters, any one of which would rank at the “good as it gets” level for rating of family stories. It would take years of research to get to the bottom of everything, and the research is all the more alluring because many of the things he did in his life left excellent documentation trails including records from the War Department, the State Department, newspaper articles and information left by our grandfather about his father. Many posts on his life will follow.

There are big mysteries in genealogical research and there are small ones. Great grandfather Edward Thomas Sandford lived a life spanning 82 years and a half dozen major chapters, any one of which would rank at the “good as it gets” level for rating of family stories. It would take years of research to get to the bottom of everything, and the research is all the more alluring because many of the things he did in his life left excellent documentation trails including records from the War Department, the State Department, newspaper articles and information left by our grandfather about his father. Many posts on his life will follow.

But right now, I am focussed on a small mystery—what to call our great grandfather? Today there is surely nobody alive who met him and, even if there was, he or she would now be 100 years old would have been a very small child at the time of the last encounter. For a clear answer, we are dependent on written records combined with reasoning.

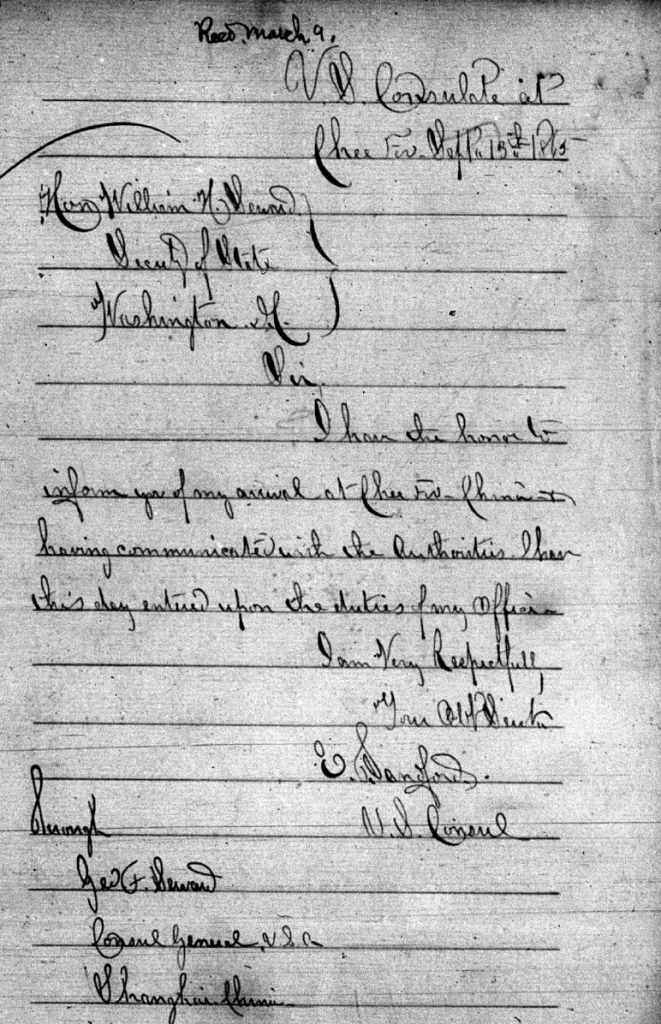

E.T. Sandford’s full name was Edward Thomas Sandford, born in 1840 in Topsham, Maine, and died in 1922 in Ontario, California. He signed most official correspondence as E.T. Sandford, and I have come to think of him as E.T. Our grandfather, Edward Joseph Sandford, followed the same pattern, being known formally as E.J. Sandford. Being used to the E.J. convention, using E.T. comes naturally. There is ample documentation to support his use of E.T, for example many of the letters he wrote to William Seward in the 1860s were signed this way. Other times, his signature was shortened to E. Sandford.

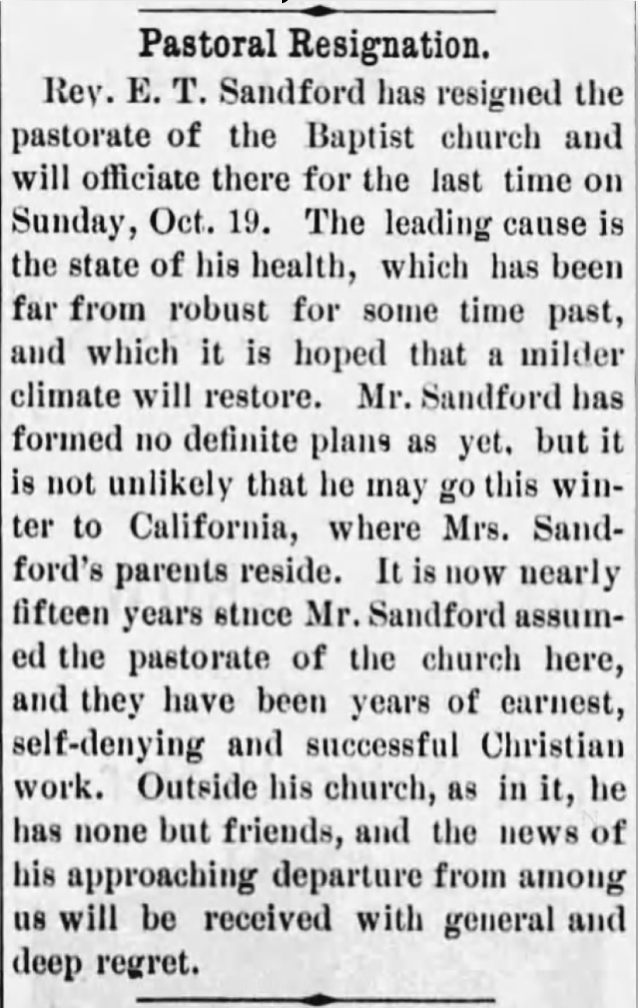

Later in his life, in the late 1880s and early 1890s, a series of newspaper articles consistently refer to him as the Rev. E.T. Sandford.

The name E.T. Sandford is used consistently,

So “E.T. Sandford” and sometimes just “E. Sandford” were used in most formal situations. But what did people who knew him call him? As a direct descendent and, as far as I know, the only person actively involved in figuring out the story of his life, I feel entitled to know the answer and to address him this way.

Our grandfather was known to friends and family as Joe throughout his life. Being the son of a man with the same first name, Edward, it would make sense that the usage of “Joe” came about at the very beginning to avoid confusion with his father. It makes sense that E.T. would have gone by “Edward” as E.J. went by “Joe”.

E.T.’s father was James Head Sandford, and his grandfather Thomas Gelston Sandford, both of Topsham, both middle names being the maiden names of their mothers. There was no first name conflict between E.T. and his father nor his grandfather, thus no evident reason why he would have gone by any name other than Edward.

E.T. had an uncle Thomas to whom he was close enough to have committed to sail around the world on one of his ships at a very early age. The name Thomas is very common in the family–it was the first name of E.T’s grandfather, great grandfather, and other ancestors and (great) uncles including the Thomas who was among the three brothers who first sailed to America around 1634. E.T’s mother was Dorothy Young Burton, so the tradition of using the mother’s maiden name as a middle name was not continued with him. The abundance of Thomas’s in E.T’s family tree suggests that his middle name was chosen to honor one or more of these ancestors, but also suggests that his family would have avoided the confusion of calling him by that name in everyday life.

For these combined reasons, I believe E.T. would have gone by “Edward” throughout his life.

Now the question of whether to shorten Edward to Ed? Going the other direction, E.J. (Joe) Sandford’s first son, E.T’s grandson (and our uncle), was also an “Edward”, Edward James Sandford— there were three Edwards in a row—and he went by “Ned”. E.T. died six months before Ned was born—there was no overlap—but our grandparents may still have wanted to have a name distinction, leading to the use of the name Ned. In view of the family history of using “Ned” for the formal Edward and “Joe” for the formal Joseph, there seems to have been a gravitation toward the use of short nicknames, and so it seems reasonable that E.T. / Edward would have gone by “Ed”.

I have found no records that definitively answer this question. In his description of his father written in 1966, Joe Sandford refers to letters that E.T. wrote home during the Civil War. I do not know the whereabouts of these letters but they would surely provide an answer, and would be fascinating in many other ways (think of a Ken Burns-style narration: “My darling Sarah….”).

I plan to look for the will of E.T.’s father, James Head Sandford, who died in Corona, California in 1898. It could contain a phrase like “to my son ___ I leave…”.

One more observation… E.T. did not spend a lot of time in close family situations between going to sea as a teenager and settling in Vermont at the age of 40+. He was home very little of the time. He had a first wife, Sarah, who was ill much of the time, but he didn’t see too much of her. He did not start a family until age 50 with his second wife. Whatever name his family and first wife used with him may not have been used very much during the middle part of his life, when his circumstances tended to be more formal and transitory—in this period he may not have had a lot of close relationships with people who would address him informally.

Having no other evidence or reasoning by which to go at this time, I conclude he used “Edward” and probably “Ed” in familiar situations. I will mostly continue to use the formal E.T. in this blog because it is a unique, unambiguous designation in the family tree which matches most of the historical records available on his life.

A final comment on genealogical research as I have come to understand it. Among several things, “Bridging the Silences” refers to filling in gaps between available historical records to understand what probably went on and developing it into a story line that is honest, accurate, and interesting. There are many situations where records simply do not exist to answer a question directly, but logical reasoning, linked with other insights into the life being studied, is useful to determine the likely answer. Short of finding an undiscovered stash of records or letters in an attic somewhere, this is often the best that can be done with the available record. In such cases, I intend always to identify my conclusions as “likely based on reasoning” vs. “proven”, but I also am comfortable embracing these types of well-reasoned conclusions in my overall understanding of the truth regarding our ancestry.

A final comment on genealogical research as I have come to understand it. Among several things, “Bridging the Silences” refers to filling in gaps between available historical records to understand what probably went on and developing it into a story line that is honest, accurate, and interesting. There are many situations where records simply do not exist to answer a question directly, but logical reasoning, linked with other insights into the life being studied, is useful to determine the likely answer. Short of finding an undiscovered stash of records or letters in an attic somewhere, this is often the best that can be done with the available record. In such cases, I intend always to identify my conclusions as “likely based on reasoning” vs. “proven”, but I also am comfortable embracing these types of well-reasoned conclusions in my overall understanding of the truth regarding our ancestry.

There are some much bigger family mysteries where we will need to rely on this kind of reasoning to find the answers. These will be discussed in future posts.